2022 GLOBAL MARKET OUTLOOK MACRO TRENDS SET TO SHAPE THE FX MARKETS

Monetary policy divergence to drive currencies

The American baseball manager and philosopher Yogi Berra famously said, “It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” We got a vivid example of that recently when the emergence of a new variant of the COVID-19 virus destroyed the market consensus and sent markets globally plunging. How can we put together an outlook for next year when the outlook for the global economy depends on random mutations of a virus? It’s hard enough under normal circumstances.

Be that as it may, investors have to put their money somewhere. With that in mind, I’d like to sketch out the outlook for next year as I see it. Rather, two outlooks: one in which the new Omicron virus turns out to be nothing major and the other where it – or some other as yet undiscovered mutation -- wreaks havoc on our world yet again. This breaks the cardinal rule of forecasting, which is that right or wrong, you have to have a view, not two views. But I see no alternative this year.

Trendless dollar

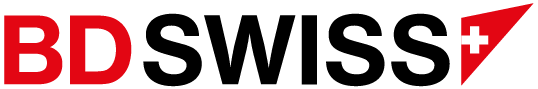

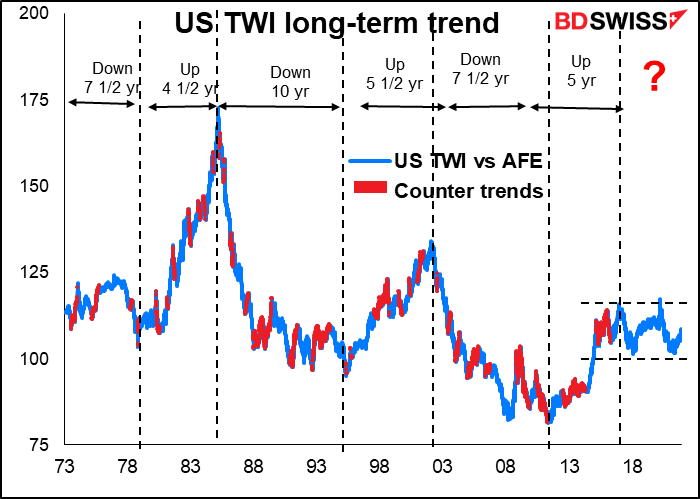

One of the reasons why it’s so hard to discern where the dollar is headed is because the long-term trend is hard to discern. Since the days of floating exchange rates began, the dollar has moved in long-term trends spanning several years. True, there were significant periods of counter-trend movement (marked red in this graph) but there was a long-term trend that was at least identifiable afterward. For several years now however, the dollar has moved sideways. It’s not clear whether the currency entered into a new downtrend that’s just taking time to get established or whether the dollar is still navigating the uptrend that started in 2011. (Graph shows the US nominal trade-weighted index vs the currencies of the advanced foreign economies.)

What we were looking at before Omicron came along

What we were looking at before Omicron came along

Let’s first discuss the outlook as I saw it a week or two ago, before the discovery of the Omicron variant. In all, the US Federal Reserve, the nation’s central bank, and its rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) are key. The Fed has promised to “taper down” its $120bn-a-month bond purchases, after which it can start raising interest rates. The key questions then were when it would end the purchases and how soon after would it start raising rates. The Fed initially planned to end the purchases by June. The debate was whether they would raise rates – “lift-off” -- immediately after or be patient and wait longer so that they could meet their mandate of “maximum employment,” which they’ve defined loosely as “broad and inclusive” employment.

The market began assuming that the Fed would hike as soon as it was finished with its bond purchases in June. In fact, it started pricing in the possibility that it would accelerate its purchases and finish them by May, allowing “lift-off” to take place in May followed by a second rate hike in June.

Now however the outlook is much less clear. We don’t know how the new variant will affect the global economy. As Fed Chair Powell said in his recent testimony to Congress:

Now however the outlook is much less clear. We don’t know how the new variant will affect the global economy. As Fed Chair Powell said in his recent testimony to Congress:

“The recent rise in COVID-19 cases and the emergence of the Omicron variant pose downside risks to employment and economic activity and increased uncertainty for inflation. Greater concerns about the virus could reduce people's willingness to work in person, which would slow progress in the labor market and intensify supply-chain disruptions.” Slower economic activity? Higher inflation? How will central banks react?

Crafting an outlook for the next year at this point reminds me of the story of the guy who’s driving around lost in the countryside. He stops to ask a farmer how to get to his destination. “Well,” the farmer replies. “If I were trying to go there, I wouldn’t start from here.” But like the driver we have no choice, so these are our possible routes.

The starting point: monetary policy convergence divergence

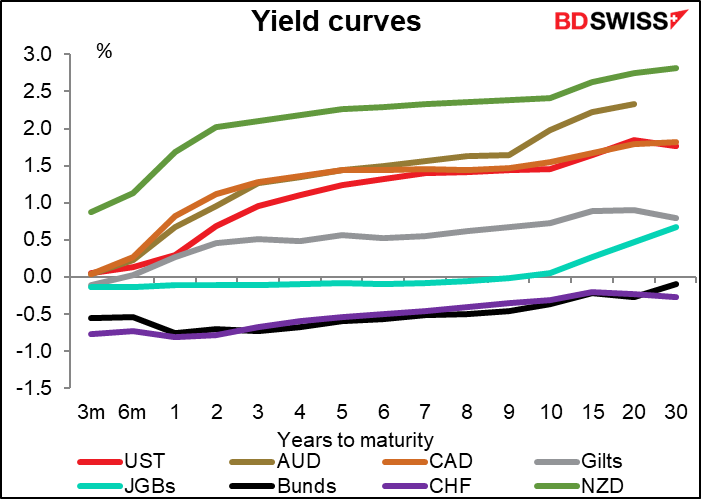

Carry trades, in which an investor borrows money in a low-interest-rate currency and invests in a higher-interest-rate currency, are usually one of the driving forces in the FX market. They became much less lucrative following the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, when central banks around the world all cut interest rates together. G10 carry trades pretty much disappeared following the pandemic as monetary policies converged on zero.

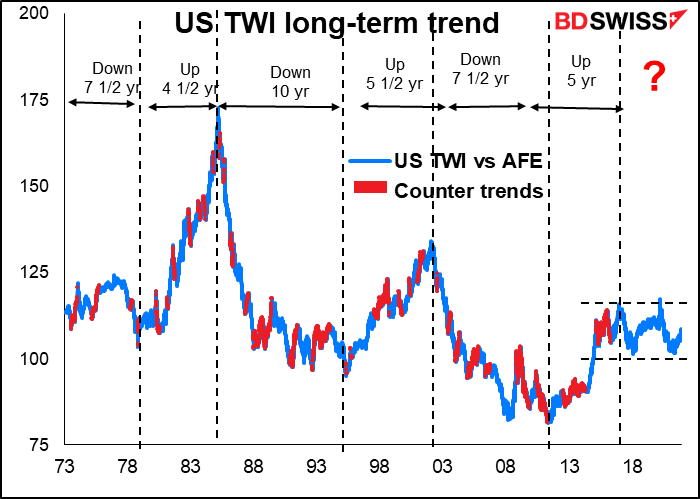

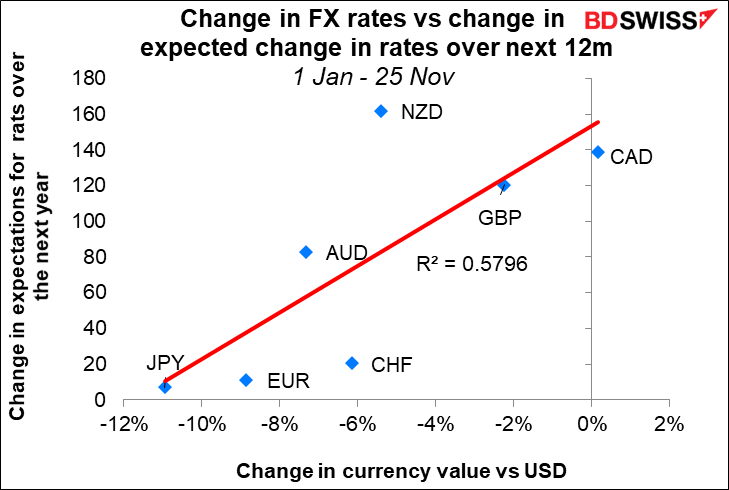

This year, the key for markets has been trying to determine the pace of monetary policy divergence. How quickly are central banks going to start raising rates and how far? Monetary policy convergence went into reverse, and we had the beginning of monetary policy divergence as different central banks were expected to raise rates at different paces. This divergence has been responsible for over half the change in currency rates this year.

This year, the key for markets has been trying to determine the pace of monetary policy divergence. How quickly are central banks going to start raising rates and how far? Monetary policy convergence went into reverse, and we had the beginning of monetary policy divergence as different central banks were expected to raise rates at different paces. This divergence has been responsible for over half the change in currency rates this year.

Omicron turns out to be mild

Omicron turns out to be mild

In the good case, if the Omicron variant turns out to be not that much worse than what we already have, I would assume the world would go on pretty much as it was planning to before this latest wave, but with a bit more caution.

That assumption seems to be what’s built into the markets now. Following the discovery of the virus, rate expectations for most countries were revised down (except for Japan, where no one expected it to raise rates anyway). However, they remain positive. People are just assuming a slower, shallower pace of tightening than they were before, but not a wholesale derailment.

That assumption seems to be what’s built into the markets now. Following the discovery of the virus, rate expectations for most countries were revised down (except for Japan, where no one expected it to raise rates anyway). However, they remain positive. People are just assuming a slower, shallower pace of tightening than they were before, but not a wholesale derailment.

That might be accurate, not only because of fears of the pandemic but also because inflation might not turn out to be as high as expected. Inflation expectations have started to turn down recently in most countries (the UK being the main exception).

I’m firmly in the “transitory” camp, even if Fed Chair Powell recently said that the word should be “retired.” Most of the recent increase in inflation is due to the impact of the pandemic. While it may take longer than expected for inflation to get back to more normal levels (hence the idea of retiring “transitory”), I still expect the global economy to gradually adjust to the “new normal” and for inflation to decline next year on its own accord.

I’m firmly in the “transitory” camp, even if Fed Chair Powell recently said that the word should be “retired.” Most of the recent increase in inflation is due to the impact of the pandemic. While it may take longer than expected for inflation to get back to more normal levels (hence the idea of retiring “transitory”), I still expect the global economy to gradually adjust to the “new normal” and for inflation to decline next year on its own accord.

As do most forecasters. With the exception of a few countries (the UK, Japan, and China being the main ones), most countries are forecast to have lower inflation in 2022 than in 2021.

As do most forecasters. With the exception of a few countries (the UK, Japan, and China being the main ones), most countries are forecast to have lower inflation in 2022 than in 2021.

The starting point: the Fed and the dollar

The starting point: the Fed and the dollar

We start with the Fed, for two reasons. First off, its actions affect the dollar, which is the metric against which all other currencies are measured. Other central banks will hesitate to hike much more aggressively than the Fed for fear that their currencies will appreciate, thereby amplifying their restrictive monetary conditions. Secondly, not only is the dollar the sun around which the other currencies revolve but also the US Treasury market exerts its gravitational pull against all other interest rate markets. If US bond yields go up, then other countries’ yields tend to go up too, albeit at a different pace, and it’s those differences that make for opportunities for FX market investments.

The question is, when can the Fed start its “lift-off”? In the testimony mentioned above, Fed Chair Powell said, “There is still ground to cover to reach maximum employment for both employment and labor force participation, and we expect progress to continue.” The unemployment rate at 4.2% is back to where it was a few years ago, but the participation rate is still well below normal.

In their quarterly Summary of Economic Projections, the median estimate of the FOMC members put “maximum employment” at around 4.0%, with most estimates ranging between 3.8% to 4.3%.

In their quarterly Summary of Economic Projections, the median estimate of the FOMC members put “maximum employment” at around 4.0%, with most estimates ranging between 3.8% to 4.3%.

Some people argue that the Fed is likely to be patient and delay hiking rates until the labor market gets back to where it was before the pandemic, i.e.., an unemployment rate of 3.5% and participation rate of 63.3. However, I think they’re more likely to accept that the structure of the US labor market has changed and a return to those levels is unlikely any time soon, particularly the participation rate as there has been a fundamental change in people’s desire to work. As a result, I think they’ll be OK starting “lift-off” with the unemployment rate approaching what they see as the longer-run level.

Some people argue that the Fed is likely to be patient and delay hiking rates until the labor market gets back to where it was before the pandemic, i.e.., an unemployment rate of 3.5% and participation rate of 63.3. However, I think they’re more likely to accept that the structure of the US labor market has changed and a return to those levels is unlikely any time soon, particularly the participation rate as there has been a fundamental change in people’s desire to work. As a result, I think they’ll be OK starting “lift-off” with the unemployment rate approaching what they see as the longer-run level.

Furthermore, they can argue as they have in the past that removing accommodation is not the same as tightening policy. Their estimate of the longer-run neutral level of the Fed funds rate has remained steady for the last three years at 2.5%. By that estimate, raising it to 0.50% or even 1.0% is not tightening policy, it’s simply providing a less accommodative policy. By that measure, it’s perfectly reasonable to start raising rates even before hitting “maximum employment.”

Outlook for the dollar: a game of two halves

Outlook for the dollar: a game of two halves

Accordingly, I would divide the year into two halves for the dollar. In the first half, I believe the dollar is likely to be supported by the anticipation of rising US interest rates. But in the second half, I think the market may be disappointed by the slow pace of the actual rate hikes. Plus by that time I would expect inflation to be coming down and for the urgency to hike rates to diminish.

Following the first rate hike either in May or June, I’d expect to see comments like this one, which followed the last rate hike in December 2018: “…the Committee will be patient as it determines what future adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate may be appropriate to support these outcomes.”

If we look at the last rate hiking cycle, which started in Dec 2015, it’s clear that it was much slower and shallower than previous hiking cycles. This would correspond to the gradual decline in what the FOMC members believe is the neutral Fed funds rate.

I think the upcoming rate hiking cycle is likely to be just as slow and shallow, if not more. The futures market, however (dotted line) is discounting a more rapid rise in rates. I think that once the Fed gets started hiking, we’re likely to see the classic “buy the rumor, sell the fact” response and the dollar may weaken in the second half of the year.

There’s another possibility though that results in the same conclusion, just a steeper path up for the dollar in the first half of the year and perhaps a steeper decline later. That is, the Fed could choose to tighten earlier and faster than expected. In his testimony to Congress, Powell said, “The economy is very strong and inflationary pressures are high. It is therefore appropriate in my view to consider wrapping up the taper of our asset purchases… perhaps a few months sooner.” That would mean the dollar would be likely to rise in the early part of the year, probably more than I would anticipate, but then fall back in the second half as other central banks caught up to the Fed.

There’s another possibility though that results in the same conclusion, just a steeper path up for the dollar in the first half of the year and perhaps a steeper decline later. That is, the Fed could choose to tighten earlier and faster than expected. In his testimony to Congress, Powell said, “The economy is very strong and inflationary pressures are high. It is therefore appropriate in my view to consider wrapping up the taper of our asset purchases… perhaps a few months sooner.” That would mean the dollar would be likely to rise in the early part of the year, probably more than I would anticipate, but then fall back in the second half as other central banks caught up to the Fed.

There are other factors that could lead to a weaker dollar by the end of the year as well. Foremost of these is the widening current account deficit. I think it could be even wider than the market expects because as the supply chain bottlenecks become unwound, US citizens are likely to do what they do best: spend, spend, spend. And much of what they spend on is imported. Notice that the current account deficit got to 5.8% of GDP during the boom times of 2006/07 before the Lehman Bros. crash, nearly double the 3.3% estimate for next year.

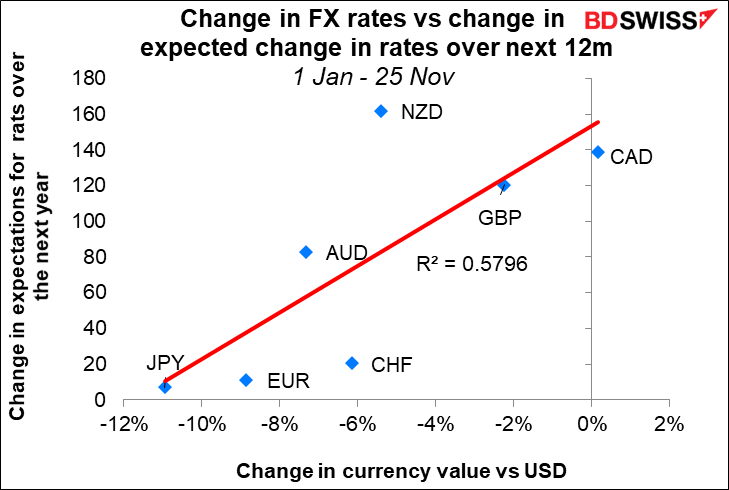

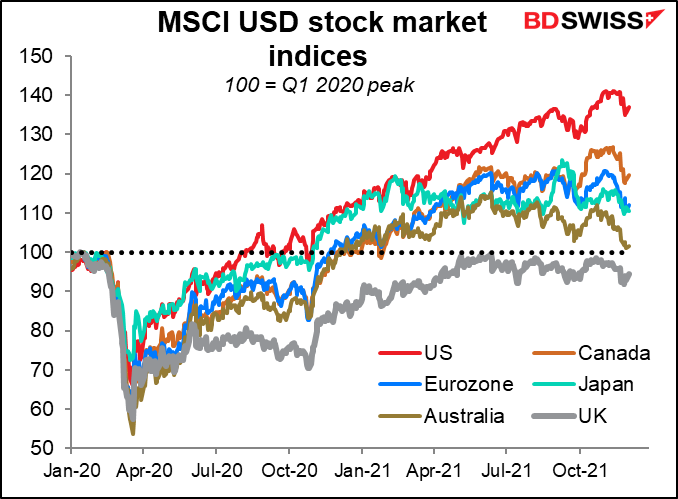

At the same time, the capital inflows that have helped the US to finance that may slow. The dollar has been buoyed recently by large inflows into US capital markets, particularly as the US stock market has outperformed other markets globally, but with US valuations high relative to other countries and many of the tech leaders that were driving the rally threatened by the new global rules on corporate taxation, the US market may prove less attractive next year.

At the same time, the capital inflows that have helped the US to finance that may slow. The dollar has been buoyed recently by large inflows into US capital markets, particularly as the US stock market has outperformed other markets globally, but with US valuations high relative to other countries and many of the tech leaders that were driving the rally threatened by the new global rules on corporate taxation, the US market may prove less attractive next year.

There is also the risk that the virus could hit the US harder than other countries. See below for more details on that.

There is also the risk that the virus could hit the US harder than other countries. See below for more details on that.

Other currencies

The first stop when evaluating currencies is always purchasing power parity (PPP). How cheap or expensive are the currencies? To evaluate this, we compare the current exchange rate with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s estimate of PPP for the various currencies.

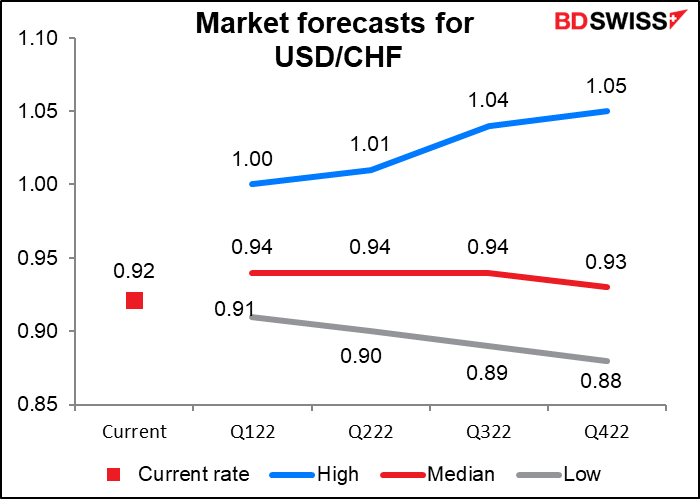

There’s a range of results. CHF is (as always) relatively overvalued, but it’s less overvalued than normal. It can still appreciate. AUD, NZD, and CAD are all fairly valued and not far away from their normal valuation; they could move either way. GBP is wildly undervalued relative to its normal rate, but this is probably a permanent change due to Brexit; it’s now pretty much in line with the undervaluation that it’s had on average since the Brexit vote. JPY seems cheap and EUR seems extremely cheap. It’s at the -20% line that often in the past results in sufficient undervaluation to improve the trade account and thereby push the value back up.

In short, valuation probably doesn’t present an obstacle for movement in either direction for most currencies except for the EUR. The downside for the EUR may well be limited from here.

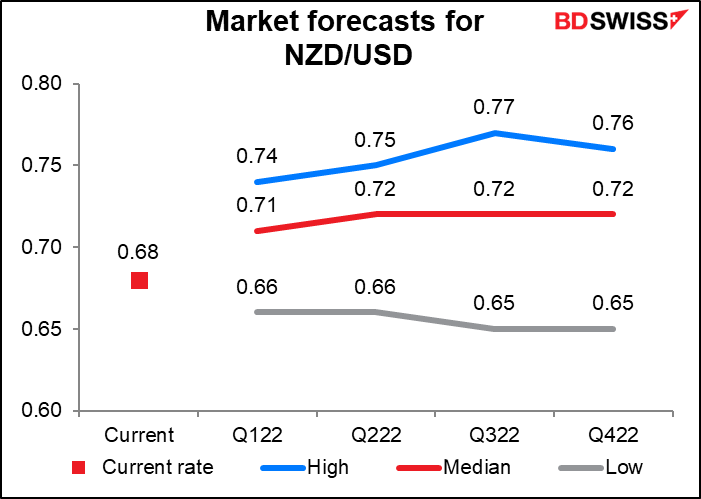

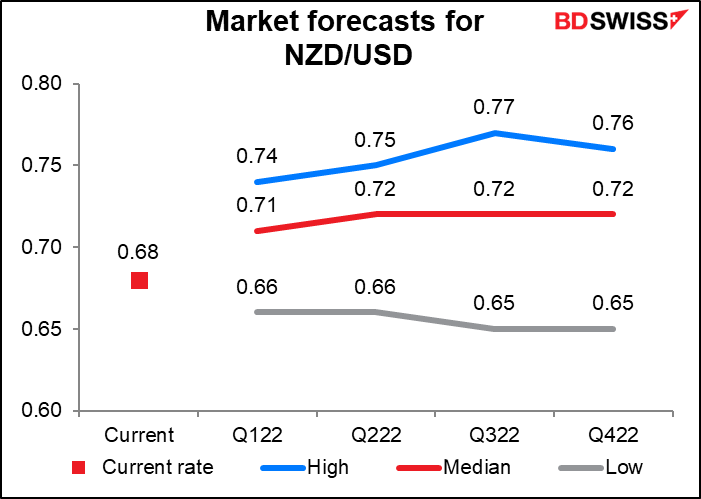

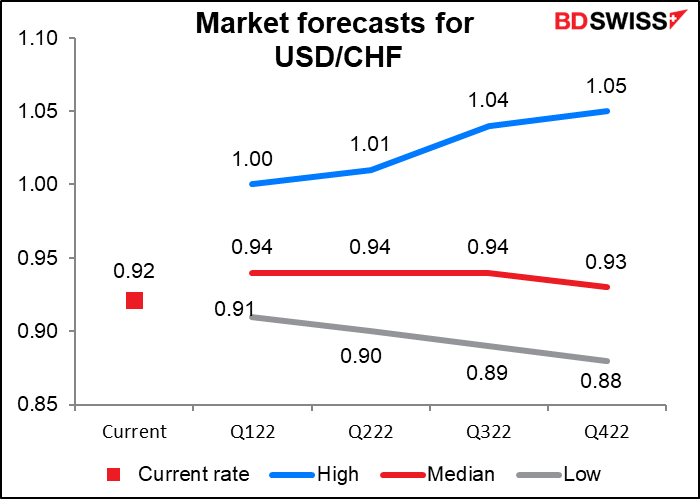

Let’s take the currencies one by one. For each, we’ll start out with the market consensus forecast from Bloomberg, which includes both the high and the low estimates for each pair. Bear in mind please that the high and low may reflect the view of just one forecaster, whereas the median is around where most forecasters are located. Nonetheless, the extremes do give you an idea of where the risks are and what the potential moves could be.

Let’s take the currencies one by one. For each, we’ll start out with the market consensus forecast from Bloomberg, which includes both the high and the low estimates for each pair. Bear in mind please that the high and low may reflect the view of just one forecaster, whereas the median is around where most forecasters are located. Nonetheless, the extremes do give you an idea of where the risks are and what the potential moves could be.

EUR: slow catch-up to the Fed?

The market is apparently assuming that the European Central Bank moves to tighten rates and that that gradually pushes up the EUR.

The market is apparently assuming that the European Central Bank moves to tighten rates and that that gradually pushes up the EUR.

I have a few observations, however: 1) Inflation in the EU isn’t expected to be as high as it is in the US. In fact, it hasn’t been expected to be as high as in the US for years now. Moreover, inflation expectations are still well within the ECB’s target, whereas they’re above target in the US.

2) The US has a habit of tightening faster than the ECB does. If we compare the latest tightening cycle in the US and Europe, the US moved much more rapidly. (We’ll ignore the abortive April 2011 tightening cycle in Europe, which only lasted seven months before they realized it was a dreadful mistake.)

2) The US has a habit of tightening faster than the ECB does. If we compare the latest tightening cycle in the US and Europe, the US moved much more rapidly. (We’ll ignore the abortive April 2011 tightening cycle in Europe, which only lasted seven months before they realized it was a dreadful mistake.)

3) The virus situation is currently much worse in Europe than it is in the US. That may delay tapering and tightening in the EU as more European countries go into lockdown and growth slows.

3) The virus situation is currently much worse in Europe than it is in the US. That may delay tapering and tightening in the EU as more European countries go into lockdown and growth slows.

The virus issue could turn around to be a negative for the US, however. The US is in a singularly bad position to fight a new, more virulent strain, for two reasons. First off, the response isn’t national but rather is done on a state-by-state basis. Around half the states are controlled by Republican nutcases who believe it is their patriotic duty to ensure that their citizens are free to die of COVID-19 if they so wish. Secondly, the country has the lowest vaccination rates among the developed nations, which ensures that they will have the chance to do so. This is a major risk for the US and the USD in Q1 of next year.

The virus issue could turn around to be a negative for the US, however. The US is in a singularly bad position to fight a new, more virulent strain, for two reasons. First off, the response isn’t national but rather is done on a state-by-state basis. Around half the states are controlled by Republican nutcases who believe it is their patriotic duty to ensure that their citizens are free to die of COVID-19 if they so wish. Secondly, the country has the lowest vaccination rates among the developed nations, which ensures that they will have the chance to do so. This is a major risk for the US and the USD in Q1 of next year.

JPY: return of the yen carry trade?

JPY: return of the yen carry trade?

The market consensus is for a weaker yen this year, and I would agree. If anything, I think the currency is likely to weaken more than the market consensus. However please remember that I have a daughter in university in Japan and so I’m naturally biased to hope for a weaker yen, so I may not be an entirely objective observer.

The market consensus is for a weaker yen this year, and I would agree. If anything, I think the currency is likely to weaken more than the market consensus. However please remember that I have a daughter in university in Japan and so I’m naturally biased to hope for a weaker yen, so I may not be an entirely objective observer.

Why the consensus forecast? Probably because Japan is assumed to be the loser in the race to normalize monetary policy. Over the next two years even Switzerland and the Eurozone are expected to start hiking rates, but not Japan.

That’s probably because the country is expected to still be well below its 2% inflation target two years from now.

That’s probably because the country is expected to still be well below its 2% inflation target two years from now.

Eventually, the BoJ may have to adjust or even lift its “yield curve control” program, which keeps the yield on the benchmark 10-year Japanese Government bond at ±25 bps around zero. However, this meeting probably isn’t the time even as other central banks move to normalize policy. Deputy Gov. Amamiya Wednesday made a speech, Japan’s Economy and Monetary Policy, in which he said:

Eventually, the BoJ may have to adjust or even lift its “yield curve control” program, which keeps the yield on the benchmark 10-year Japanese Government bond at ±25 bps around zero. However, this meeting probably isn’t the time even as other central banks move to normalize policy. Deputy Gov. Amamiya Wednesday made a speech, Japan’s Economy and Monetary Policy, in which he said:

"I am sometimes asked whether there is no need for Japan to adjust monetary easing while central banks in the United States and Europe have recently started to move toward adjusting theirs. [...] Given the price developments in Japan I have described, I think it makes sense that the Bank does not actually need to adjust its large-scale monetary easing at present. Central banks conduct monetary policies in line with developments in economic activities and prices of their respective economies. It is therefore natural that the specifics of and directions for their monetary policies are not the same, and this difference will instead contribute to stability in their economies as well as the global economy.”

Amamiya isn’t kidding. Japan’s inflation situation is categorically different from that of other countries, even low-inflation Switzerland. Accordingly, its monetary policy should be, too.

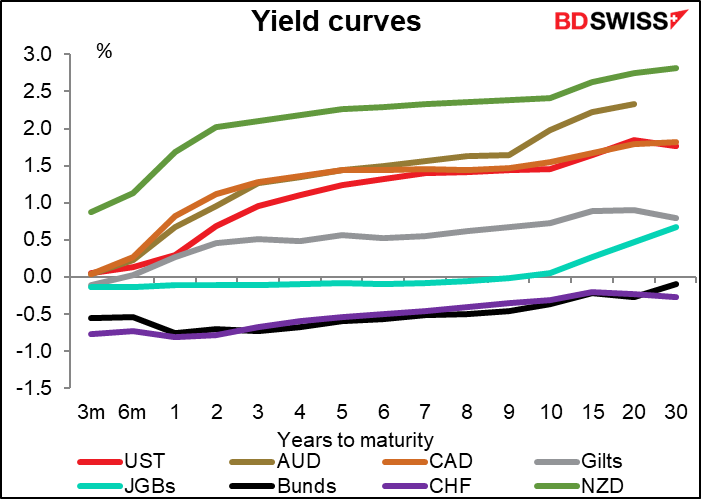

In short, I think the BoJ is likely to remain on hold while other central banks raise rates and watch their bond markets respond accordingly. The widening yield differential between Japan and other nations is likely to act as a magnet drawing funds out of Japan and weakening the currency.

In short, I think the BoJ is likely to remain on hold while other central banks raise rates and watch their bond markets respond accordingly. The widening yield differential between Japan and other nations is likely to act as a magnet drawing funds out of Japan and weakening the currency.

Accordingly, I think Japan is likely to be the funding currency of choice for the next several years. The return of the “yen carry trade” is likely to see the return of a weak yen, in my view. (The “yen carry trade” refers to the period in the late 1990s when Japan’s interest rates were far below those of any other country and people around the world were borrowing money in yen to fund anything and everything, which caused the yen to weaken dramatically.)

Furthermore, the Bank of Japan still has in place its “yield curve control” policy, in which it limits the movement of the 10-year bond to ±25 bps around zero. As other central banks raise their rate, bond yields in those countries are likely to be dragged higher. Not Japan! So with yield spreads widening, Japanese investors are likely to invest more money abroad, further pushing down the currency.

The main question though is, will the authorities change their view on the currency? Up to now the Ministry of Finance was focused on encouraging exports and had a bias for a weaker currency. Now that the country has a trade deficit though perhaps they’re more concerned with ensuring affordable imports and wouldn’t want to see the yen weaken too much further. Verbal intervention by the authorities could limit the downside for the yen (or upside for USD/JPY, to be more precise).

The main question though is, will the authorities change their view on the currency? Up to now the Ministry of Finance was focused on encouraging exports and had a bias for a weaker currency. Now that the country has a trade deficit though perhaps they’re more concerned with ensuring affordable imports and wouldn’t want to see the yen weaken too much further. Verbal intervention by the authorities could limit the downside for the yen (or upside for USD/JPY, to be more precise).

The real value of the yen against the country’s major trading partners (real effective exchange rate, or REER) hasn’t yet reached the level that usually signals a turnaround, however.

One other factor limiting the yen’s downside is positioning. The yen has been speculators’ #1short for several months now. It was only replaced recently by AUD. There might not be that many more people left to get in the trade.

One other factor limiting the yen’s downside is positioning. The yen has been speculators’ #1short for several months now. It was only replaced recently by AUD. There might not be that many more people left to get in the trade.

Risk to the forecast: It’s possible that as the global inflation rate rises, Japan’s could, too. Japan’s corporate goods price index, known elsewhere in the world as the producer price index, has been soaring recently. It hit 9.0% YoY in November, the fastest pace of growth since 1980. The final goods PPI rose at the fastest pace since 1981.

Risk to the forecast: It’s possible that as the global inflation rate rises, Japan’s could, too. Japan’s corporate goods price index, known elsewhere in the world as the producer price index, has been soaring recently. It hit 9.0% YoY in November, the fastest pace of growth since 1980. The final goods PPI rose at the fastest pace since 1981.

The rise is being driven by higher raw material prices, which are really soaring – up 74.6% YoY!!! That’s the highest rate of growth since the oil shock days of 1974. Intermediate materials were up 15.7% YoY.

The rise is being driven by higher raw material prices, which are really soaring – up 74.6% YoY!!! That’s the highest rate of growth since the oil shock days of 1974. Intermediate materials were up 15.7% YoY.

If companies grow tired of absorbing these higher producer prices in their margins, we could see inflation coming back to Japan after a nearly 30-year absence. That would cause a sea change for the Japanese economy and monetary policy – and the yen.

If companies grow tired of absorbing these higher producer prices in their margins, we could see inflation coming back to Japan after a nearly 30-year absence. That would cause a sea change for the Japanese economy and monetary policy – and the yen.

GBP: A “Wiley E. Coyote” moment?

I have to admit: I hate the pound. I think that by all rights it should be at parity with the euro – hell, parity with the Italian Lira if it still existed, or maybe the Greek Drachma (OK, that’s a bit excessive; there’d be some 301 GDR to the dollar right now if it were still around). But still, the currency seems to me to be like Wiley E. Coyote in the “Road Runner” cartoons, running off the cliff and still running until he looks down…

I have to admit: I hate the pound. I think that by all rights it should be at parity with the euro – hell, parity with the Italian Lira if it still existed, or maybe the Greek Drachma (OK, that’s a bit excessive; there’d be some 301 GDR to the dollar right now if it were still around). But still, the currency seems to me to be like Wiley E. Coyote in the “Road Runner” cartoons, running off the cliff and still running until he looks down…

The forces all seem arrayed against the pound:

The forces all seem arrayed against the pound:

The country’s current account is continually in deficit, thanks to a structural deficit in merchandise trade. Oddly enough, Brexit may have improved that performance somewhat. The Centre for European Reform (CER) estimates that Brexit has reduced Britain’s trade in goods by some 11%-16% If we assume that both imports and exports are affected to the same degree, then since imports are greater than exports, the trade deficit should be somewhat narrower (although the impact on the exchange rate might be offset by the fact that the economy as a whole would be smaller as a result).

The country depends on trade in services to offset the deficit in merchandise trade, the Achilles Heel of the economy. And there the hit may be much greater because it’s easier to wipe out an entire business in services than in goods. With services, a lot of the drop in trade is just due to the expense of carrying out the paperwork. Some companies will find it worthwhile to pay the price, some won’t. But with services, if a country doesn’t license another country to carry out certain services (e.g. managing assets or selling insurance) then bam! The whole business ends.

Unfortunately, Bloomberg doesn’t have a breakdown of where the country’s service-sector exports go, but I imagine a large percentage goes to the EU, as does 51.5% of merchandise exports (still!).

The UK and EU still haven’t worked out the details of their trade agreement for services, but already Brexit has resulted in an estimated 5.7% decline in service exports, according to a recent paper on Brexit and Services Trade. The paper also observed that “Given liberalising services trade is generally more challenging than goods, it is extremely hard, if indeed possible at all, to expect future FTAs (free trade agreements) to achieve new market access in a significant way. After all, gravity dictates that services trade is typically greatest with nearest trading partners.”

The UK and EU still haven’t worked out the details of their trade agreement for services, but already Brexit has resulted in an estimated 5.7% decline in service exports, according to a recent paper on Brexit and Services Trade. The paper also observed that “Given liberalising services trade is generally more challenging than goods, it is extremely hard, if indeed possible at all, to expect future FTAs (free trade agreements) to achieve new market access in a significant way. After all, gravity dictates that services trade is typically greatest with nearest trading partners.”

We now have to wait to see if PM Johnson triggers Article 16 and manages to blow up the entire Brexit agreement that took so long to negotiate in the first place. Of course, it was always impossible to square the circle of Northern Ireland: to work out an agreement that would allow NI to be both in the EU and in the UK at the same time. NI isn’t a quantum qubit that can be in two states at the same time.

Since services account for not only much of UK trade but also 80% of economic activity and 82% of employment, failure to agree on trade in services would be extremely damaging to the UK.

Where does Britain’s services income come from? About half is from direct investment, half from portfolio investment.

Direct investment has shrunk a lot since the Brexit referendum. I’d expect it to shrink even more with the continued friction between the UK and the EU and the internal problems besetting the UK economy.

As for portfolio investment, much of that is equities.

As for portfolio investment, much of that is equities.

The UK is the only major world stock market that hasn’t regained its pre-pandemic peak yet in USD terms. (That’s not just because of currency valuation – the FTSE 100 index of major shares hasn’t regained the peak in local currency terms, although the FTSE 250 index of mostly local companies has.)

The UK is the only major world stock market that hasn’t regained its pre-pandemic peak yet in USD terms. (That’s not just because of currency valuation – the FTSE 100 index of major shares hasn’t regained the peak in local currency terms, although the FTSE 250 index of mostly local companies has.)

Now, an argument could be made that UK equities could be a good investment because they’re likely to catch up with the rest of the world…but if you were a fund manager, would you bet your career on that? Everyone in finance knows that “past performance is no guarantee of future performance.” At the same time, everyone also knows Newton’s first law of motion, which is “a body in motion tends to stay in motion unless acted upon by some external force.” What’s the external force that’s going to change the trajectory of UK stocks? I can’t see anything good coming down the line soon. Maybe the current administration will finally implode and the Prime Minister will be replaced by someone who knows what he or she is doing. But that will take some time, during which the market is likely to be even rockier.

That leaves higher gilts yields to attract money in. Given that UK yields are now toward the bottom of the pack in the G10, that would require a substantial rise in interest rates – a rise that the Bank of England would probably not want to see in these fragile times. Accordingly, I expect the pound to take the strain and adjust downward until UK assets become more attractive to international investors.

That leaves higher gilts yields to attract money in. Given that UK yields are now toward the bottom of the pack in the G10, that would require a substantial rise in interest rates – a rise that the Bank of England would probably not want to see in these fragile times. Accordingly, I expect the pound to take the strain and adjust downward until UK assets become more attractive to international investors.

The main argument I can see against this one is that the pound has suffered so much already, any further problems are already in the price. Not necessarily! The currency’s real effective exchange rate is only about average nowadays. A further 10% downside on this measure would be nothing extraordinary.

The main argument I can see against this one is that the pound has suffered so much already, any further problems are already in the price. Not necessarily! The currency’s real effective exchange rate is only about average nowadays. A further 10% downside on this measure would be nothing extraordinary.

Moreover, Brexit has caused the UK economy to shrink. Estimates are that even before the UK left the EU, the economy was 1%-3% smaller because of foregone consumption and investment (as well as the depreciation of sterling). The government estimates that the economy will be 4%-5% smaller by 2030. Slower growth means a slower increase in productivity and less incentive for foreign investment – all negatives for the currency.

Moreover, Brexit has caused the UK economy to shrink. Estimates are that even before the UK left the EU, the economy was 1%-3% smaller because of foregone consumption and investment (as well as the depreciation of sterling). The government estimates that the economy will be 4%-5% smaller by 2030. Slower growth means a slower increase in productivity and less incentive for foreign investment – all negatives for the currency.

The commodity currencies: AUD, NZD, CAD

Does it make sense to deal with the three commodity currencies together? I think so. The correlations between them are at fairly high levels historically, especially AUD & CAD. This suggests that the market is lumping them all together to a great degree.

Does it make sense to deal with the three commodity currencies together? I think so. The correlations between them are at fairly high levels historically, especially AUD & CAD. This suggests that the market is lumping them all together to a great degree.

Much of their fate will be determined by what happens in China. The recent loosening of monetary policy there, including two cuts in the Required Reserve Ratio (RRR) for banks, is a good sign for future growth in China – and therefore the global manufacturing cycle.

Much of their fate will be determined by what happens in China. The recent loosening of monetary policy there, including two cuts in the Required Reserve Ratio (RRR) for banks, is a good sign for future growth in China – and therefore the global manufacturing cycle.

That should also help to underpin global metal prices, which are a major factor in determining AUD’s value.

That should also help to underpin global metal prices, which are a major factor in determining AUD’s value.

Given that 62% of New Zealand’s exports are edibles, one might assume that global agricultural prices would be much more important for NZD than metal prices, but one would be wrong (except for milk). My research shows that the currency is more correlated with commodity prices overall and with energy prices –even though New Zealand doesn’t export any oil or coal – than with agricultural commodities. My guess is that the FX market isn’t so discerning and that traders just think “commodities” without necessarily thinking which commodities.

Given that 62% of New Zealand’s exports are edibles, one might assume that global agricultural prices would be much more important for NZD than metal prices, but one would be wrong (except for milk). My research shows that the currency is more correlated with commodity prices overall and with energy prices –even though New Zealand doesn’t export any oil or coal – than with agricultural commodities. My guess is that the FX market isn’t so discerning and that traders just think “commodities” without necessarily thinking which commodities.

As the economic cycle turns up, the prices of commodities should rise faster than the prices of manufactured goods, causing the terms of trade for the commodity currencies to improve and allowing them to appreciate.

Of course, this reliance on China can cut both ways. Monetary and fiscal stimulus is getting less effective in producing growth in China, thanks to the miracle of diminishing marginal returns. With the real estate sector in serious trouble in the country, growth in China could also be in more trouble than the government can contain simply by monetary meddling.

Of course, this reliance on China can cut both ways. Monetary and fiscal stimulus is getting less effective in producing growth in China, thanks to the miracle of diminishing marginal returns. With the real estate sector in serious trouble in the country, growth in China could also be in more trouble than the government can contain simply by monetary meddling.

A recent paper (Peak China Housing, by Harvard Prof. Kenneth Rogoff and IMF economist Yuanchen Yang), estimated that “in 2016, real estate and construction industries combined accounted for around 29% of China’s GDP, comparable only by pre-crisis Spain and Ireland…Real estate not only accounts for 23% of household consumption, but it also connects to various sectors of the economy through investment, construction, and the financial system.” The two economists estimate that “a 20% fall in real estate activity could lead to a 5-10% fall in GDP, even without amplification from a banking crisis, or accounting for the importance of real estate as collateral.” This leaves AUD and NZD vulnerable to a downturn in Chinese construction which, if Evergrande is any indication, seems possible if not likely.

A recent paper (Peak China Housing, by Harvard Prof. Kenneth Rogoff and IMF economist Yuanchen Yang), estimated that “in 2016, real estate and construction industries combined accounted for around 29% of China’s GDP, comparable only by pre-crisis Spain and Ireland…Real estate not only accounts for 23% of household consumption, but it also connects to various sectors of the economy through investment, construction, and the financial system.” The two economists estimate that “a 20% fall in real estate activity could lead to a 5-10% fall in GDP, even without amplification from a banking crisis, or accounting for the importance of real estate as collateral.” This leaves AUD and NZD vulnerable to a downturn in Chinese construction which, if Evergrande is any indication, seems possible if not likely.

The other area of vulnerability for the commodity currencies, particularly NZD, is if the market starts reassessing the likely degree of tightening during the coming year. Since NZD has the highest degree of tightening already priced in (followed by CAD), if investors start to think that central banks aren’t likely to be as aggressive as currently estimated, then NZD is likely to undergo the greatest revision of estimates, followed by CAD. That would be negative for the currencies.

CAD: watch out for oil

While CAD is classified among the commodity currencies, its fate is tied up closely with one commodity in particular: oil. There’s a very close correlation between USD/CAD and the Bank of Canada’s energy price index (comprised of the prices of coal, oil, and natural gas).

CAD: watch out for oil

While CAD is classified among the commodity currencies, its fate is tied up closely with one commodity in particular: oil. There’s a very close correlation between USD/CAD and the Bank of Canada’s energy price index (comprised of the prices of coal, oil, and natural gas).

The oil industry seems to agree that oil is likely to fall next year, as supply increases faster than demand (see below). If that happens, I would expect CAD to decline somewhat. It’s been the best-performing of the three commodity currencies this year, indeed the best-performing of all the G10 currencies (even gaining slightly against USD). But assuming China growth holds up and oil prices slip, it could be the worst-performing of the three.

The oil industry seems to agree that oil is likely to fall next year, as supply increases faster than demand (see below). If that happens, I would expect CAD to decline somewhat. It’s been the best-performing of the three commodity currencies this year, indeed the best-performing of all the G10 currencies (even gaining slightly against USD). But assuming China growth holds up and oil prices slip, it could be the worst-performing of the three.

Switzerland: part of the pandemic unwind

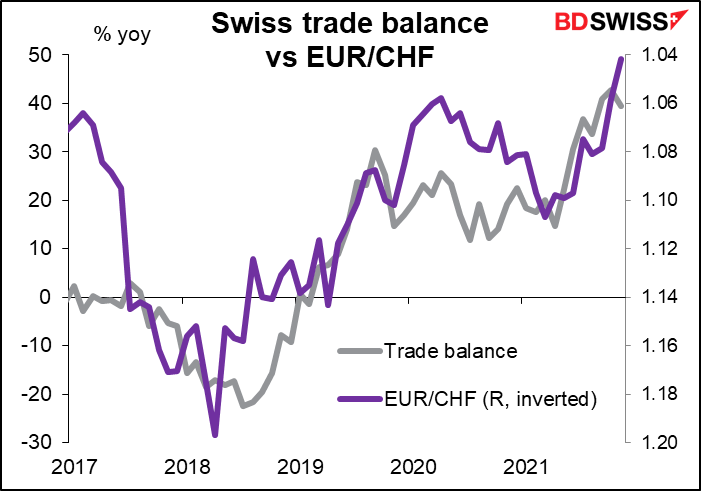

EUR/CHF is at its lowest level since June 2015, a few months after the Swiss National Bank (SNB) pulled the rug out from under the EUR/CHF floor (Jan 2015). What ever happened to the SNB Bank Council’s oft-repeated pledge that it “remains willing to intervene in the foreign exchange market as necessary, in order to counter upward pressure on the Swiss franc”?

EUR/CHF is at its lowest level since June 2015, a few months after the Swiss National Bank (SNB) pulled the rug out from under the EUR/CHF floor (Jan 2015). What ever happened to the SNB Bank Council’s oft-repeated pledge that it “remains willing to intervene in the foreign exchange market as necessary, in order to counter upward pressure on the Swiss franc”?

There’s no doubt that the Swiss franc remains highly valued – on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis it’s the most overvalued currency in the world, both according to the OECD’s calculations and the Economist’s less-scientific Big Mac Index. Nonetheless, there are some doubts about the SNB’s willingness to intervene in the FX market. As the graph below shows, they’ve intervened significantly less this year at each level of EUR/CHF than in previous years.

Perhaps they’re happy with the return of inflation to 1.5% and therefore don’t think they need to intervene as much -- although some of us would argue that given the preternaturally high price level in Switzerland, the country needs serious deflation, not inflation.

Perhaps they think it’s inevitable, given the way the Swiss economy has outperformed the Eurozone economy since the pandemic began.

Perhaps they think it’s inevitable, given the way the Swiss economy has outperformed the Eurozone economy since the pandemic began.

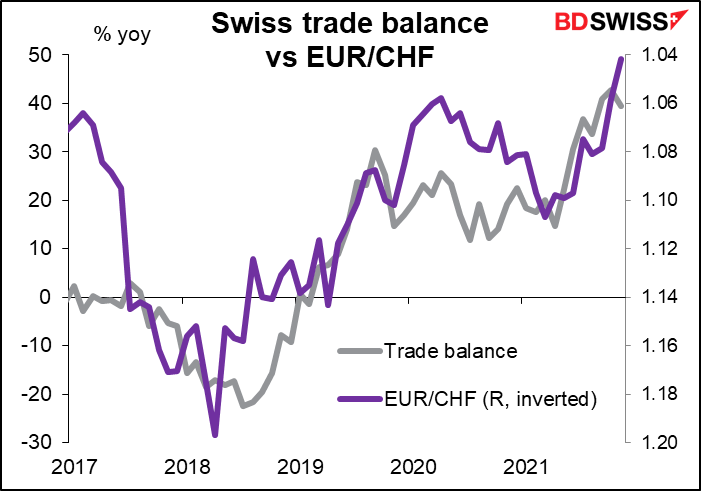

One reason the Swiss economy might be doing better than the Eurozone economy is that Swiss exports have held up well, causing a rise in the trade surplus.

One reason the Swiss economy might be doing better than the Eurozone economy is that Swiss exports have held up well, causing a rise in the trade surplus.

EUR/CHF has largely tracked the trade balance.

EUR/CHF has largely tracked the trade balance.

The yield advantage of CHF bonds vs German bunds (or more accurately the yield disadvantage of Bunds relative to CHF bonds, since both are negative) has narrowed considerably this year. That should’ve made it easier for the Swiss to recycle their trade surplus through portfolio investment.

The yield advantage of CHF bonds vs German bunds (or more accurately the yield disadvantage of Bunds relative to CHF bonds, since both are negative) has narrowed considerably this year. That should’ve made it easier for the Swiss to recycle their trade surplus through portfolio investment.

However, portfolio investment abroad is just a small part of the recycling of the Swiss trade surplus. Direct investment is usually larger, but the Swiss have stopped direct investment abroad during the pandemic. Meanwhile, the central bank has pulled back from intervention (as mentioned above).

However, portfolio investment abroad is just a small part of the recycling of the Swiss trade surplus. Direct investment is usually larger, but the Swiss have stopped direct investment abroad during the pandemic. Meanwhile, the central bank has pulled back from intervention (as mentioned above).

What’s to come? I agree with the market consensus of a higher EUR/CHF (weaker CHF vs EUR), mostly because I think Swiss companies will resume investing abroad. Furthermore, as interest rates around the world normalize, I would expect the “other investments” category – which includes loans – to move to an outflow as investors use CHF as a funding currency (along with JPY). Although CHF rates are expected to rise a tad faster than EUR rates (something I find difficult to imagine, but never mind), since they’re starting off 25 bps below EUR rates, they can rise a bit faster and still be below EUR rates. That makes CHF a good funding currency.

What’s to come? I agree with the market consensus of a higher EUR/CHF (weaker CHF vs EUR), mostly because I think Swiss companies will resume investing abroad. Furthermore, as interest rates around the world normalize, I would expect the “other investments” category – which includes loans – to move to an outflow as investors use CHF as a funding currency (along with JPY). Although CHF rates are expected to rise a tad faster than EUR rates (something I find difficult to imagine, but never mind), since they’re starting off 25 bps below EUR rates, they can rise a bit faster and still be below EUR rates. That makes CHF a good funding currency.

Oil: a game of two halves Why might OPEC+ do that? The group expects – and the US agrees, by the way – that the oil market is likely to be oversupplied next year and prices will fall. OPEC’s Economic Commission Board, a group of economists that advise the cartel, Thursday warned that the increase from the various SPRs, possibly totalling 66mn barrels, would swell the global surplus by 1.1mn barrels a day (b/d) to 2.3mn b/d in January and 3.7mn b/d in February. This is a difference in degree, not direction, from the outlook in the US Energy Information Agency’s Short-Term Energy Outlook of Dec. 7th, which forecast that “growth in production from OPEC+, of U.S. tight oil, and from other non-OPEC countries will outpace slowing growth in global oil consumption, especially in light of renewed concerns about COVID-19 variants.” As a result, the US expects Brent prices to average $71/barrel in December and $73/bbl Q1 2022 (1Q22). For 2022 as a whole they expect Brent to average $70/bbl.

But as we go further out, the forecasts become less reliable. Both demand and supply become uncertain. Demand, because we don’t know what the impact of the virus will be. Will it fade or will it get worse? If the impact fades and countries lift their restrictions, then demand is likely to return to normal (or above).

For supply, there are several unknowns. While OPEC+ is supposed to increase its output by 400k b/d every month, they may not be able to achieve this target as most OPEC+ members already have significant capacity constraints and may be unable to raise their output. Among OPEC countries, only Saudi Arabia, the U.A.E., and legally constrained Iran to have any significant spare capacity left. For OPEC+ as a whole to meet its production targets, Saudi Arabia and Russia would have to exceed their quotas significantly, which the other members probably wouldn’t welcome.

Secondly, there’s a big question mark over Iran’s production, currently 2.52mn b/d or 9% of OPEC’s total output. If the Biden Administration works out some agreement with Iran – which looks increasingly unlikely – they could get the freedom to sell more oil. They have the capacity to pump 1.3mn b/d more so that would change the equation significantly. But if they don’t – which looks likely -- then their ability to maintain their oilfields will likely deteriorate, causing their output to fall. Ditto for Venezuela, also the object of a US trade embargo.

Secondly, there’s a big question mark over Iran’s production, currently 2.52mn b/d or 9% of OPEC’s total output. If the Biden Administration works out some agreement with Iran – which looks increasingly unlikely – they could get the freedom to sell more oil. They have the capacity to pump 1.3mn b/d more so that would change the equation significantly. But if they don’t – which looks likely -- then their ability to maintain their oilfields will likely deteriorate, causing their output to fall. Ditto for Venezuela, also the object of a US trade embargo.

Finally, there’s a question over US production, which still hasn’t returned to pre-pandemic levels. That could also change the supply/demand picture by 1mn b/d and without the complicating factor of multinational negotiations.

I think in the second half of the year, as economic activity gets back to normal (assuming economic activity gets back to normal!) oil prices could rise further.

I think in the second half of the year, as economic activity gets back to normal (assuming economic activity gets back to normal!) oil prices could rise further.

The sad fact is, higher oil prices are needed to accomplish another goal of President Biden’s, that is, the switch to renewable energy. Nothing encourages investment in windmills and solar panels quite like $100/bbl oil. Not to mention that higher oil prices will be necessary to offset the risks involved in undertaking further exploration and development of long-term oil projects against the background of increasing pressure from the ESG movement (Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance) to move away from fossil fuels. Otherwise, there’s a risk of a serious debilitating spike in prices at some point in the decades before the transition to renewable energy is complete. As they say in the oil business, “high prices cure high prices.”

The sad fact is, higher oil prices are needed to accomplish another goal of President Biden’s, that is, the switch to renewable energy. Nothing encourages investment in windmills and solar panels quite like $100/bbl oil. Not to mention that higher oil prices will be necessary to offset the risks involved in undertaking further exploration and development of long-term oil projects against the background of increasing pressure from the ESG movement (Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance) to move away from fossil fuels. Otherwise, there’s a risk of a serious debilitating spike in prices at some point in the decades before the transition to renewable energy is complete. As they say in the oil business, “high prices cure high prices.”

Footnote: how accurate are the market’s forecasts?

In this article, I’ve supplied the consensus forecasts from Bloomberg for the major currencies. How accurate are they likely to be? There’s no way to know that ahead of time. What we can do however is compare the forecast moves with the previous year’s forecasts moves and ask, are these forecasts reasonable?

What we can see is: for every currency except NZD, the consensus market forecast is for less movement than the median year.

That’s certainly not impossible, but is it likely? In fact, the volatility of currencies has been falling for the last several years. It popped back up because of the pandemic but has since fallen back. It is entirely possible that we get a year of below-median volatility. But then again, we didn’t expect to get a global pandemic in 2020, did we?

That’s certainly not impossible, but is it likely? In fact, the volatility of currencies has been falling for the last several years. It popped back up because of the pandemic but has since fallen back. It is entirely possible that we get a year of below-median volatility. But then again, we didn’t expect to get a global pandemic in 2020, did we?

The American baseball manager and philosopher Yogi Berra famously said, “It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” We got a vivid example of that recently when the emergence of a new variant of the COVID-19 virus destroyed the market consensus and sent markets globally plunging. How can we put together an outlook for next year when the outlook for the global economy depends on random mutations of a virus? It’s hard enough under normal circumstances.

Be that as it may, investors have to put their money somewhere. With that in mind, I’d like to sketch out the outlook for next year as I see it. Rather, two outlooks: one in which the new Omicron virus turns out to be nothing major and the other where it – or some other as yet undiscovered mutation -- wreaks havoc on our world yet again. This breaks the cardinal rule of forecasting, which is that right or wrong, you have to have a view, not two views. But I see no alternative this year.

Trendless dollar

One of the reasons why it’s so hard to discern where the dollar is headed is because the long-term trend is hard to discern. Since the days of floating exchange rates began, the dollar has moved in long-term trends spanning several years. True, there were significant periods of counter-trend movement (marked red in this graph) but there was a long-term trend that was at least identifiable afterward. For several years now however, the dollar has moved sideways. It’s not clear whether the currency entered into a new downtrend that’s just taking time to get established or whether the dollar is still navigating the uptrend that started in 2011. (Graph shows the US nominal trade-weighted index vs the currencies of the advanced foreign economies.)

What we were looking at before Omicron came along

What we were looking at before Omicron came alongLet’s first discuss the outlook as I saw it a week or two ago, before the discovery of the Omicron variant. In all, the US Federal Reserve, the nation’s central bank, and its rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) are key. The Fed has promised to “taper down” its $120bn-a-month bond purchases, after which it can start raising interest rates. The key questions then were when it would end the purchases and how soon after would it start raising rates. The Fed initially planned to end the purchases by June. The debate was whether they would raise rates – “lift-off” -- immediately after or be patient and wait longer so that they could meet their mandate of “maximum employment,” which they’ve defined loosely as “broad and inclusive” employment.

The market began assuming that the Fed would hike as soon as it was finished with its bond purchases in June. In fact, it started pricing in the possibility that it would accelerate its purchases and finish them by May, allowing “lift-off” to take place in May followed by a second rate hike in June.

Now however the outlook is much less clear. We don’t know how the new variant will affect the global economy. As Fed Chair Powell said in his recent testimony to Congress:

Now however the outlook is much less clear. We don’t know how the new variant will affect the global economy. As Fed Chair Powell said in his recent testimony to Congress:“The recent rise in COVID-19 cases and the emergence of the Omicron variant pose downside risks to employment and economic activity and increased uncertainty for inflation. Greater concerns about the virus could reduce people's willingness to work in person, which would slow progress in the labor market and intensify supply-chain disruptions.” Slower economic activity? Higher inflation? How will central banks react?

Crafting an outlook for the next year at this point reminds me of the story of the guy who’s driving around lost in the countryside. He stops to ask a farmer how to get to his destination. “Well,” the farmer replies. “If I were trying to go there, I wouldn’t start from here.” But like the driver we have no choice, so these are our possible routes.

The starting point: monetary policy convergence divergence

Carry trades, in which an investor borrows money in a low-interest-rate currency and invests in a higher-interest-rate currency, are usually one of the driving forces in the FX market. They became much less lucrative following the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, when central banks around the world all cut interest rates together. G10 carry trades pretty much disappeared following the pandemic as monetary policies converged on zero.

This year, the key for markets has been trying to determine the pace of monetary policy divergence. How quickly are central banks going to start raising rates and how far? Monetary policy convergence went into reverse, and we had the beginning of monetary policy divergence as different central banks were expected to raise rates at different paces. This divergence has been responsible for over half the change in currency rates this year.

This year, the key for markets has been trying to determine the pace of monetary policy divergence. How quickly are central banks going to start raising rates and how far? Monetary policy convergence went into reverse, and we had the beginning of monetary policy divergence as different central banks were expected to raise rates at different paces. This divergence has been responsible for over half the change in currency rates this year. Omicron turns out to be mild

Omicron turns out to be mildIn the good case, if the Omicron variant turns out to be not that much worse than what we already have, I would assume the world would go on pretty much as it was planning to before this latest wave, but with a bit more caution.

That assumption seems to be what’s built into the markets now. Following the discovery of the virus, rate expectations for most countries were revised down (except for Japan, where no one expected it to raise rates anyway). However, they remain positive. People are just assuming a slower, shallower pace of tightening than they were before, but not a wholesale derailment.

That assumption seems to be what’s built into the markets now. Following the discovery of the virus, rate expectations for most countries were revised down (except for Japan, where no one expected it to raise rates anyway). However, they remain positive. People are just assuming a slower, shallower pace of tightening than they were before, but not a wholesale derailment.That might be accurate, not only because of fears of the pandemic but also because inflation might not turn out to be as high as expected. Inflation expectations have started to turn down recently in most countries (the UK being the main exception).

I’m firmly in the “transitory” camp, even if Fed Chair Powell recently said that the word should be “retired.” Most of the recent increase in inflation is due to the impact of the pandemic. While it may take longer than expected for inflation to get back to more normal levels (hence the idea of retiring “transitory”), I still expect the global economy to gradually adjust to the “new normal” and for inflation to decline next year on its own accord.

I’m firmly in the “transitory” camp, even if Fed Chair Powell recently said that the word should be “retired.” Most of the recent increase in inflation is due to the impact of the pandemic. While it may take longer than expected for inflation to get back to more normal levels (hence the idea of retiring “transitory”), I still expect the global economy to gradually adjust to the “new normal” and for inflation to decline next year on its own accord. As do most forecasters. With the exception of a few countries (the UK, Japan, and China being the main ones), most countries are forecast to have lower inflation in 2022 than in 2021.

As do most forecasters. With the exception of a few countries (the UK, Japan, and China being the main ones), most countries are forecast to have lower inflation in 2022 than in 2021. The starting point: the Fed and the dollar

The starting point: the Fed and the dollarWe start with the Fed, for two reasons. First off, its actions affect the dollar, which is the metric against which all other currencies are measured. Other central banks will hesitate to hike much more aggressively than the Fed for fear that their currencies will appreciate, thereby amplifying their restrictive monetary conditions. Secondly, not only is the dollar the sun around which the other currencies revolve but also the US Treasury market exerts its gravitational pull against all other interest rate markets. If US bond yields go up, then other countries’ yields tend to go up too, albeit at a different pace, and it’s those differences that make for opportunities for FX market investments.

The question is, when can the Fed start its “lift-off”? In the testimony mentioned above, Fed Chair Powell said, “There is still ground to cover to reach maximum employment for both employment and labor force participation, and we expect progress to continue.” The unemployment rate at 4.2% is back to where it was a few years ago, but the participation rate is still well below normal.

In their quarterly Summary of Economic Projections, the median estimate of the FOMC members put “maximum employment” at around 4.0%, with most estimates ranging between 3.8% to 4.3%.

In their quarterly Summary of Economic Projections, the median estimate of the FOMC members put “maximum employment” at around 4.0%, with most estimates ranging between 3.8% to 4.3%. Some people argue that the Fed is likely to be patient and delay hiking rates until the labor market gets back to where it was before the pandemic, i.e.., an unemployment rate of 3.5% and participation rate of 63.3. However, I think they’re more likely to accept that the structure of the US labor market has changed and a return to those levels is unlikely any time soon, particularly the participation rate as there has been a fundamental change in people’s desire to work. As a result, I think they’ll be OK starting “lift-off” with the unemployment rate approaching what they see as the longer-run level.

Some people argue that the Fed is likely to be patient and delay hiking rates until the labor market gets back to where it was before the pandemic, i.e.., an unemployment rate of 3.5% and participation rate of 63.3. However, I think they’re more likely to accept that the structure of the US labor market has changed and a return to those levels is unlikely any time soon, particularly the participation rate as there has been a fundamental change in people’s desire to work. As a result, I think they’ll be OK starting “lift-off” with the unemployment rate approaching what they see as the longer-run level.Furthermore, they can argue as they have in the past that removing accommodation is not the same as tightening policy. Their estimate of the longer-run neutral level of the Fed funds rate has remained steady for the last three years at 2.5%. By that estimate, raising it to 0.50% or even 1.0% is not tightening policy, it’s simply providing a less accommodative policy. By that measure, it’s perfectly reasonable to start raising rates even before hitting “maximum employment.”

Outlook for the dollar: a game of two halves

Outlook for the dollar: a game of two halvesAccordingly, I would divide the year into two halves for the dollar. In the first half, I believe the dollar is likely to be supported by the anticipation of rising US interest rates. But in the second half, I think the market may be disappointed by the slow pace of the actual rate hikes. Plus by that time I would expect inflation to be coming down and for the urgency to hike rates to diminish.

Following the first rate hike either in May or June, I’d expect to see comments like this one, which followed the last rate hike in December 2018: “…the Committee will be patient as it determines what future adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate may be appropriate to support these outcomes.”

If we look at the last rate hiking cycle, which started in Dec 2015, it’s clear that it was much slower and shallower than previous hiking cycles. This would correspond to the gradual decline in what the FOMC members believe is the neutral Fed funds rate.

I think the upcoming rate hiking cycle is likely to be just as slow and shallow, if not more. The futures market, however (dotted line) is discounting a more rapid rise in rates. I think that once the Fed gets started hiking, we’re likely to see the classic “buy the rumor, sell the fact” response and the dollar may weaken in the second half of the year.

There’s another possibility though that results in the same conclusion, just a steeper path up for the dollar in the first half of the year and perhaps a steeper decline later. That is, the Fed could choose to tighten earlier and faster than expected. In his testimony to Congress, Powell said, “The economy is very strong and inflationary pressures are high. It is therefore appropriate in my view to consider wrapping up the taper of our asset purchases… perhaps a few months sooner.” That would mean the dollar would be likely to rise in the early part of the year, probably more than I would anticipate, but then fall back in the second half as other central banks caught up to the Fed.

There’s another possibility though that results in the same conclusion, just a steeper path up for the dollar in the first half of the year and perhaps a steeper decline later. That is, the Fed could choose to tighten earlier and faster than expected. In his testimony to Congress, Powell said, “The economy is very strong and inflationary pressures are high. It is therefore appropriate in my view to consider wrapping up the taper of our asset purchases… perhaps a few months sooner.” That would mean the dollar would be likely to rise in the early part of the year, probably more than I would anticipate, but then fall back in the second half as other central banks caught up to the Fed.There are other factors that could lead to a weaker dollar by the end of the year as well. Foremost of these is the widening current account deficit. I think it could be even wider than the market expects because as the supply chain bottlenecks become unwound, US citizens are likely to do what they do best: spend, spend, spend. And much of what they spend on is imported. Notice that the current account deficit got to 5.8% of GDP during the boom times of 2006/07 before the Lehman Bros. crash, nearly double the 3.3% estimate for next year.

At the same time, the capital inflows that have helped the US to finance that may slow. The dollar has been buoyed recently by large inflows into US capital markets, particularly as the US stock market has outperformed other markets globally, but with US valuations high relative to other countries and many of the tech leaders that were driving the rally threatened by the new global rules on corporate taxation, the US market may prove less attractive next year.

At the same time, the capital inflows that have helped the US to finance that may slow. The dollar has been buoyed recently by large inflows into US capital markets, particularly as the US stock market has outperformed other markets globally, but with US valuations high relative to other countries and many of the tech leaders that were driving the rally threatened by the new global rules on corporate taxation, the US market may prove less attractive next year. There is also the risk that the virus could hit the US harder than other countries. See below for more details on that.

There is also the risk that the virus could hit the US harder than other countries. See below for more details on that.Other currencies

The first stop when evaluating currencies is always purchasing power parity (PPP). How cheap or expensive are the currencies? To evaluate this, we compare the current exchange rate with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s estimate of PPP for the various currencies.

There’s a range of results. CHF is (as always) relatively overvalued, but it’s less overvalued than normal. It can still appreciate. AUD, NZD, and CAD are all fairly valued and not far away from their normal valuation; they could move either way. GBP is wildly undervalued relative to its normal rate, but this is probably a permanent change due to Brexit; it’s now pretty much in line with the undervaluation that it’s had on average since the Brexit vote. JPY seems cheap and EUR seems extremely cheap. It’s at the -20% line that often in the past results in sufficient undervaluation to improve the trade account and thereby push the value back up.

In short, valuation probably doesn’t present an obstacle for movement in either direction for most currencies except for the EUR. The downside for the EUR may well be limited from here.

Let’s take the currencies one by one. For each, we’ll start out with the market consensus forecast from Bloomberg, which includes both the high and the low estimates for each pair. Bear in mind please that the high and low may reflect the view of just one forecaster, whereas the median is around where most forecasters are located. Nonetheless, the extremes do give you an idea of where the risks are and what the potential moves could be.

Let’s take the currencies one by one. For each, we’ll start out with the market consensus forecast from Bloomberg, which includes both the high and the low estimates for each pair. Bear in mind please that the high and low may reflect the view of just one forecaster, whereas the median is around where most forecasters are located. Nonetheless, the extremes do give you an idea of where the risks are and what the potential moves could be.EUR: slow catch-up to the Fed?

The market is apparently assuming that the European Central Bank moves to tighten rates and that that gradually pushes up the EUR.

The market is apparently assuming that the European Central Bank moves to tighten rates and that that gradually pushes up the EUR.I have a few observations, however: 1) Inflation in the EU isn’t expected to be as high as it is in the US. In fact, it hasn’t been expected to be as high as in the US for years now. Moreover, inflation expectations are still well within the ECB’s target, whereas they’re above target in the US.

2) The US has a habit of tightening faster than the ECB does. If we compare the latest tightening cycle in the US and Europe, the US moved much more rapidly. (We’ll ignore the abortive April 2011 tightening cycle in Europe, which only lasted seven months before they realized it was a dreadful mistake.)

2) The US has a habit of tightening faster than the ECB does. If we compare the latest tightening cycle in the US and Europe, the US moved much more rapidly. (We’ll ignore the abortive April 2011 tightening cycle in Europe, which only lasted seven months before they realized it was a dreadful mistake.) 3) The virus situation is currently much worse in Europe than it is in the US. That may delay tapering and tightening in the EU as more European countries go into lockdown and growth slows.

3) The virus situation is currently much worse in Europe than it is in the US. That may delay tapering and tightening in the EU as more European countries go into lockdown and growth slows. The virus issue could turn around to be a negative for the US, however. The US is in a singularly bad position to fight a new, more virulent strain, for two reasons. First off, the response isn’t national but rather is done on a state-by-state basis. Around half the states are controlled by Republican nutcases who believe it is their patriotic duty to ensure that their citizens are free to die of COVID-19 if they so wish. Secondly, the country has the lowest vaccination rates among the developed nations, which ensures that they will have the chance to do so. This is a major risk for the US and the USD in Q1 of next year.

The virus issue could turn around to be a negative for the US, however. The US is in a singularly bad position to fight a new, more virulent strain, for two reasons. First off, the response isn’t national but rather is done on a state-by-state basis. Around half the states are controlled by Republican nutcases who believe it is their patriotic duty to ensure that their citizens are free to die of COVID-19 if they so wish. Secondly, the country has the lowest vaccination rates among the developed nations, which ensures that they will have the chance to do so. This is a major risk for the US and the USD in Q1 of next year. JPY: return of the yen carry trade?

JPY: return of the yen carry trade? The market consensus is for a weaker yen this year, and I would agree. If anything, I think the currency is likely to weaken more than the market consensus. However please remember that I have a daughter in university in Japan and so I’m naturally biased to hope for a weaker yen, so I may not be an entirely objective observer.

The market consensus is for a weaker yen this year, and I would agree. If anything, I think the currency is likely to weaken more than the market consensus. However please remember that I have a daughter in university in Japan and so I’m naturally biased to hope for a weaker yen, so I may not be an entirely objective observer.Why the consensus forecast? Probably because Japan is assumed to be the loser in the race to normalize monetary policy. Over the next two years even Switzerland and the Eurozone are expected to start hiking rates, but not Japan.

That’s probably because the country is expected to still be well below its 2% inflation target two years from now.

That’s probably because the country is expected to still be well below its 2% inflation target two years from now. Eventually, the BoJ may have to adjust or even lift its “yield curve control” program, which keeps the yield on the benchmark 10-year Japanese Government bond at ±25 bps around zero. However, this meeting probably isn’t the time even as other central banks move to normalize policy. Deputy Gov. Amamiya Wednesday made a speech, Japan’s Economy and Monetary Policy, in which he said:

Eventually, the BoJ may have to adjust or even lift its “yield curve control” program, which keeps the yield on the benchmark 10-year Japanese Government bond at ±25 bps around zero. However, this meeting probably isn’t the time even as other central banks move to normalize policy. Deputy Gov. Amamiya Wednesday made a speech, Japan’s Economy and Monetary Policy, in which he said:"I am sometimes asked whether there is no need for Japan to adjust monetary easing while central banks in the United States and Europe have recently started to move toward adjusting theirs. [...] Given the price developments in Japan I have described, I think it makes sense that the Bank does not actually need to adjust its large-scale monetary easing at present. Central banks conduct monetary policies in line with developments in economic activities and prices of their respective economies. It is therefore natural that the specifics of and directions for their monetary policies are not the same, and this difference will instead contribute to stability in their economies as well as the global economy.”

Amamiya isn’t kidding. Japan’s inflation situation is categorically different from that of other countries, even low-inflation Switzerland. Accordingly, its monetary policy should be, too.

In short, I think the BoJ is likely to remain on hold while other central banks raise rates and watch their bond markets respond accordingly. The widening yield differential between Japan and other nations is likely to act as a magnet drawing funds out of Japan and weakening the currency.

In short, I think the BoJ is likely to remain on hold while other central banks raise rates and watch their bond markets respond accordingly. The widening yield differential between Japan and other nations is likely to act as a magnet drawing funds out of Japan and weakening the currency.Accordingly, I think Japan is likely to be the funding currency of choice for the next several years. The return of the “yen carry trade” is likely to see the return of a weak yen, in my view. (The “yen carry trade” refers to the period in the late 1990s when Japan’s interest rates were far below those of any other country and people around the world were borrowing money in yen to fund anything and everything, which caused the yen to weaken dramatically.)