Weekly Outlook

How high is too high?

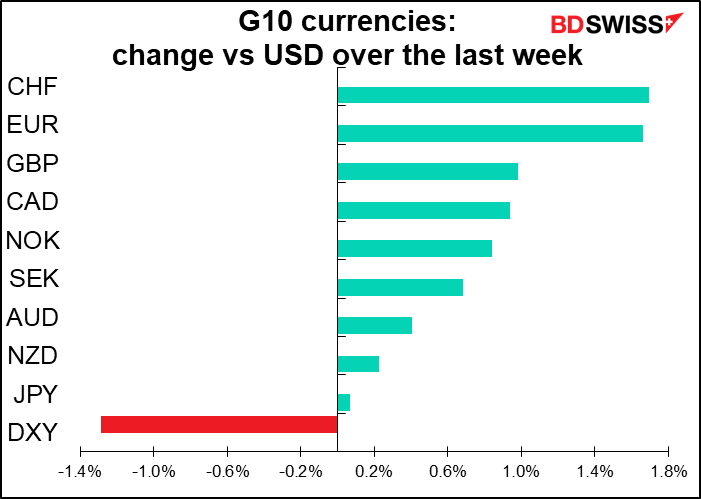

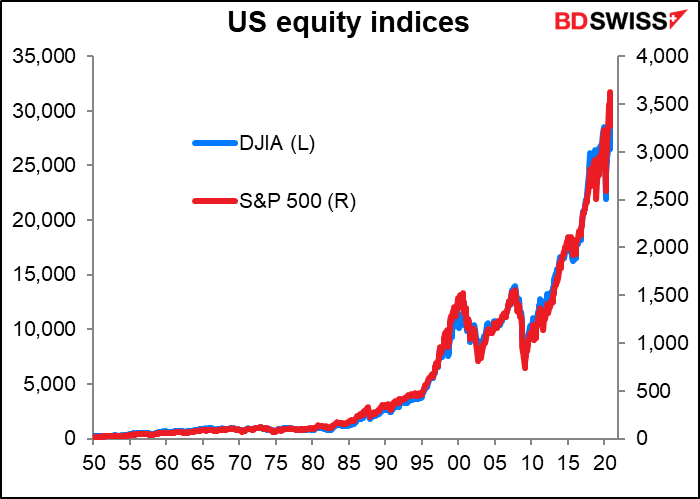

As the S&P 500 and NASDAQ indices both moved further into record-high territory this week…

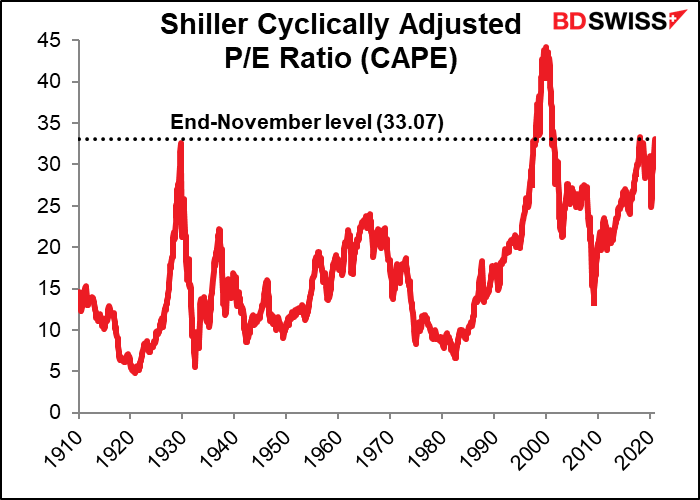

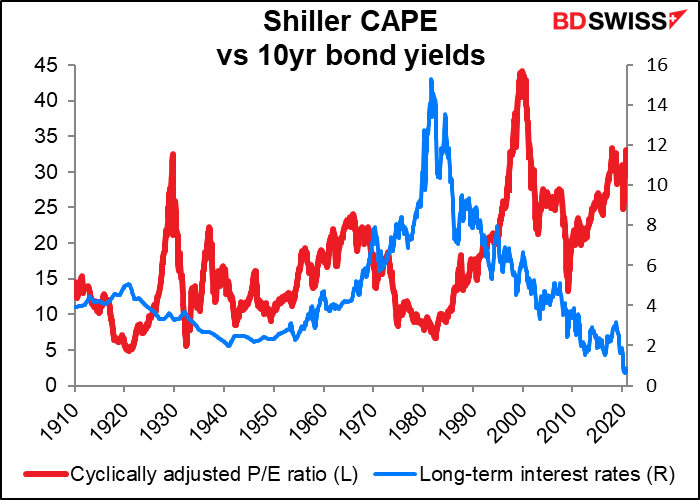

…this other graph grabbed a lot of media attention. The end-month data for November showed the measure at a level that’s only been exceeded twice before: in 1929 and 1999. Neither of those years was followed by particularly good times for stock market investors.

It’s the cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio, or CAPE. It’s a measure of how cheap or expensive stocks are, devised by Yale finance professor Robert Schiller, author of the famous book on market valuation, Irrational Exuberance. According to Wikipedia:

The cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio, commonly known as CAPE, Shiller P/E, or P/E 10 ratio, is a valuation measure usually applied to the US S&P 500 equity market. It is defined as price divided by the average of ten years of earnings (moving average), adjusted for inflation. As such, it is principally used to assess likely future returns from equities over timescales of 10 to 20 years, with higher-than-average CAPE values implying lower-than-average long-term annual average returns.

Using average earnings over the last decade helps to smooth out the impact of business cycles and other events and gives a better picture of a company’s sustainable earning power.

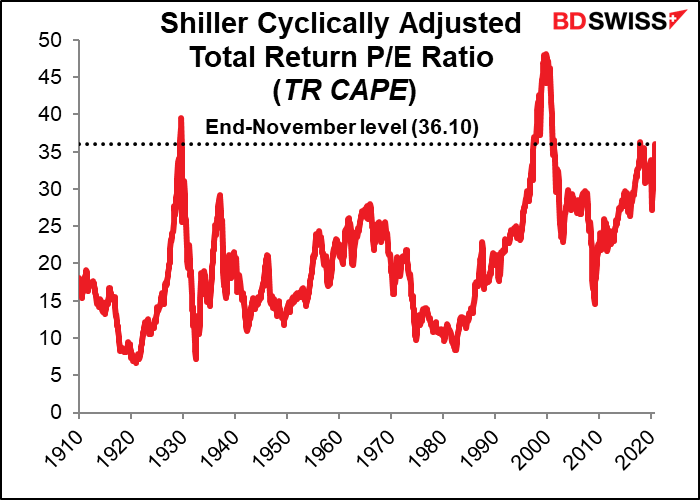

Prof. Shiller started producing an adjusted version several years ago to take into account the change in American business practices to emphasize stock buy-backs rather than dividends. The story there is the same, too:

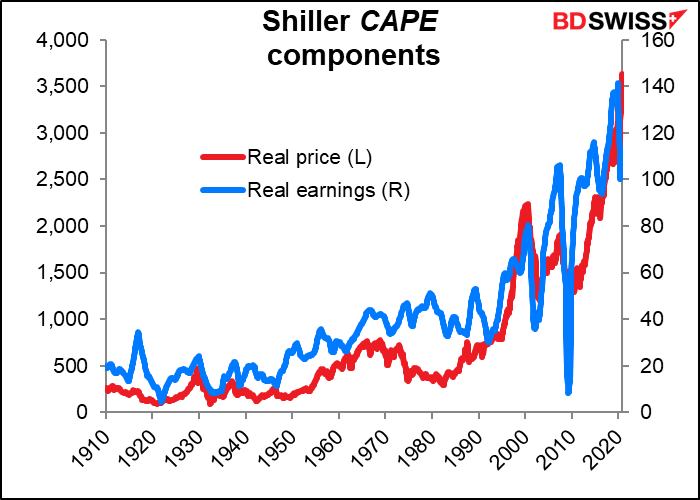

The real growth in the price of stocks (after taking inflation into account) has massively outstripped the growth in the earnings of companies. Tesla is the poster child for this phenomenon of course, at a 12m trailing P/E ratio of 901x or consensus forward P/E of 153x. But even such an established company as Amazon.com Inc trades at a trailing P/E of 93.7.

This is the other set of graphs that’s grabbed people’s attention: the CAPE vs the yield available in the bond market. The P/E ratio is extremely high, while the yield available on bonds is extremely low.

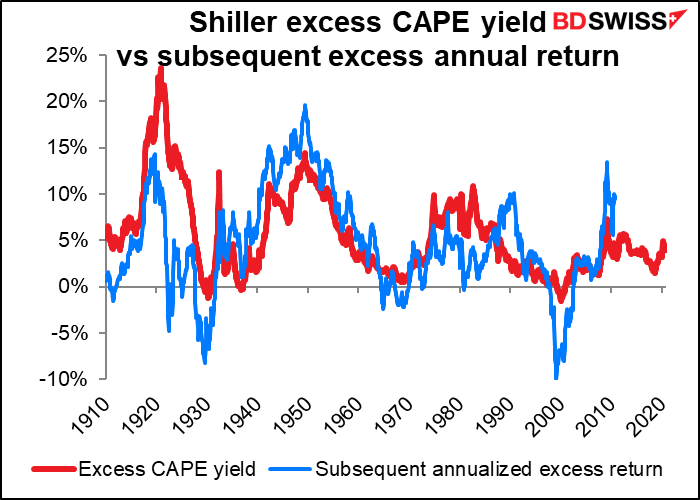

The excess CAPE yield is the earnings yield on the S&P 500 (the inverse of the P/E ratio) minus the long-term interest rate, all in real terms. That’s a measure of how much more companies are yielding than bonds are. Prof. Schiller discovered that when that measure was high, the return on stocks over the next 10 years tended to be high. Conversely, when that measure was low, the return on stocks over the next 10 years tended to be low. Guess what it is now.

Of course, estimates of the stock market’s return over the next 10 years are of little interest to people who are day-trading or scalping the market for a point or two here and there. Prof. Schiller’s work is of more interest to institutional investors and others with a long-term perspective. People evaluating a company on fundamental grounds would’ve never gotten in on Tesla this year, for example.

Furthermore, if you’re not in stocks, you have to answer the troubling question: what do you do with your money? With interest rates at or near record lows, that’s not an easy one, either. Bonds offer puny returns – the “risk-free rate of interest” nowadays is more like the “interest-free rate of risk.” Real estate prices are high too. Hedge funds have underperformed a simply S&P index fund for years. No easy answer. That may explain in part why stock prices are so high: no obvious alternative.

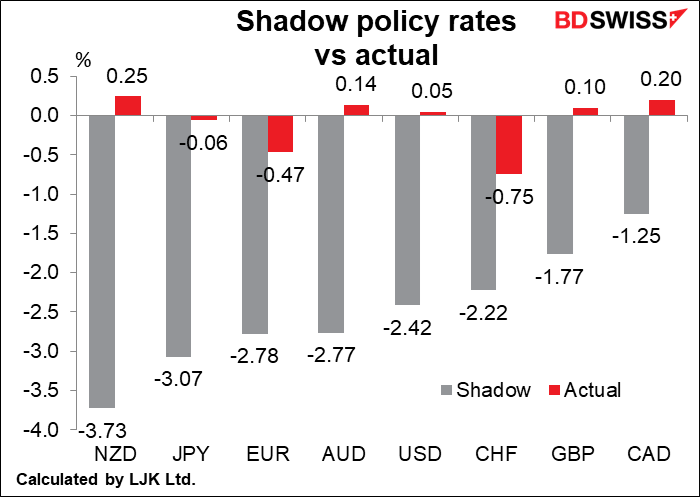

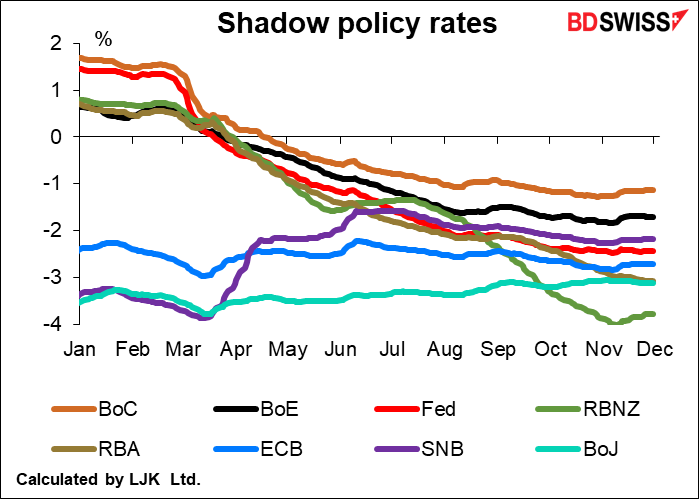

Nor is it easy to see what would change things at the moment. Central banks are actively aiding and abetting this crime against investment common sense. We can tell that from the “shadow policy rates.”.

With interest rates at or below zero, central banks have resorted to other, extraordinary measures to loosen monetary policy. This makes it difficult to judge what the overall monetary stance of a central bank is and to compare monetary regimes across currencies. The “shadow policy rate” attempts to estimate the overall impact of a central bank’s easing measures and convert it into a figure equivalent to a policy rate at the level that would be necessary to cause a similar effect. The data are calculated by Leo Krippner, a researcher at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, and published on his website, LJK Macro Finance Analysis.

The major central banks’ shadow policy rates are all well into negative territory, in contrast to the nominal policy rates, which in some cases are stuck at what the central banks argue is the “zero bound.”

Earlier this year it was just the Bank of Japan (BoJ), Swiss National Bank (SNB) and the European Central Bank (ECB) that had below-zero rates. Now the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) leads the way and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is at about the same level as the inventor of the “zero-interest-rate policy” aka ZIRP: the BoJ. Remember, NZD and AUD used to be known as “high-yielding currencies.”

The key to central bank behavior seems to be that not only is inflation vanquished – none of the major industrial countries has had a problem with above-target inflation for years now – but more to the point, it’s no longer even the target of monetary policy. The target of monetary policy is shifting from restraining inflation to resuscitating employment and other social problems. This is most evident in the US, where the Fed’s new Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy set out first the Fed’s goals in terms of employment before dealing with inflation. It’s also clear in Australia, where the Reserve Bank of Australia said that “The Board views addressing the high rate of unemployment as an important national priority” – not necessarily getting inflation back up to target. The December statement mentioned employment eight times but inflation only five. And of course the RBNZ added employment to its mandate last year, in April 2019.

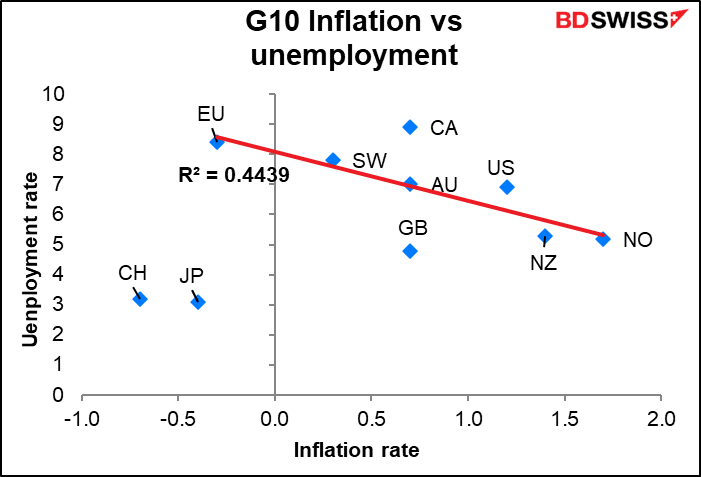

Other central banks may not be spelling it out quite so explicitly, but of course the “Philips Curve” model that they operate under implies that getting unemployment down should in theory also help to push inflation up. The two goals are therefore effectively the same at current levels of below-target inflation. And in fact, excluding Japan and Switzerland, two countries with unusually low unemployment rates, the relationship holds pretty well.

Other central banks are focusing on other issues as well. The ECB is taking on climate change – for example, Bank of France Gov. Villeroy said the ECB should consider climate risks in collateral rules. The link between central banking and climate change was symbolized by former Bank of England Gov. Carney’s appointment as UN special envoy for climate action and finance.

Here’s how one person on Twitter (Frances Donald of Manulife Investments) expressed the new approach by central banks:

Next week: Brexit, ECB, Bank of Canada

No rest for the weary! I thought that after the US election was over, maybe I could relax a bit. Not yet! Next week we have a number of important events.

The main focus, as always, will be Brexit. With the Brexit negotiations, I feel like I’m back in high school, trying to find out from my friends whether that cute girl in French class likes me or not. Some of her friends say she does. Others say she doesn’t. Some say she does, but the next day say she doesn’t. Sometimes I see her in the hall and smile at her and she smiles back. Sometimes she ignores me. But the prom is coming up next week, so we’ll finally find out for sure. That’s Thursday and Friday. The European Council meets on Thursday to discuss COVID-19, climate change, security, and external relations. Then on Friday there will be Euro Summit to discuss the banking union and capital markets union. But you know whatever the official agenda is, the real agenda will have three main topics: Brexit, Brexit and Brexit.

In theory, it would be nice if EU Chief Negotiator Barnier had something to put forward to the leaders at this summit, who could then render their judgment and, one hopes, send the approved treaty off to the national parliaments to be ratified. HAH! They’ve missed every deadline so far, why not miss this one too? Some senior UK officials are pointing to the 2010/12 Greek debt negotiations, where every decision came at 11:55 PM Sunday night. They argue that 18 December could be the last date for an agreement that would still provide enough time to have it ratified by national parliaments. Others argue that the EU could make a decision as late as 28 December by splitting the decision into solely EU-wide matters and those that involve individual countries and deciding on the former without having to get the decision ratified by national parliaments.

To make matters worse, some people are now raising the possibility that the EU doesn’t even want an agreement this year. That it would be better for the EU to let Britain crash out on 1 January with no agreement. The idea is that the worse things are for the UK, the more willing they’ll be to make concessions later in the year.

Meanwhile, there are reports that some Continental trucking companies plan to deal with the certain chaos at UK ports by simply refusing to accept cargoes for the UK. That’ll be great. At least it may help the Bank of England to meet its inflation target.

ECB: readying a bazooka?

The other big event next week is the final European Central Bank (ECB) meeting of the year on Thursday. Back in October, they as good as promised further action:

The new round of Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections in December will allow a thorough reassessment of the economic outlook and the balance of risks. On the basis of this updated assessment, the Governing Council will recalibrate its instruments, as appropriate, to respond to the unfolding situation…

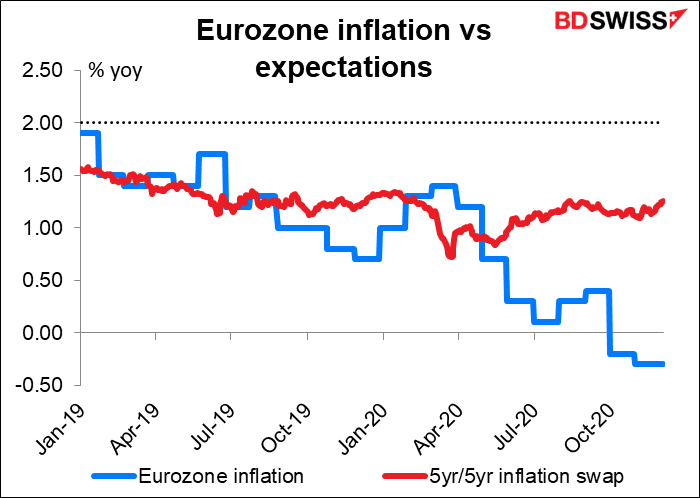

The new forecasts are likely to downgrade the outook significantly. Q3 growth exceeded the ECB’s forecasts, but thanks to the reimposed lockdowns, Q4 is likely to show a contraction, vs the 3.1% qoq rise in activity the ECB was expecting. That will impact the growth outlook for 2021, if not beyond. Meanwhile, the Eurozone is in increasingly deep deflation, although inflation expectations have stopped declining recently. The new forecasts for inflation are unlikely to show it returning to the target level by 2023.

What is the ECB likely to do in response? Various officials have hinted that the Governing Council is more likely to adjust its extraordinary policy measures than to push interest rates further into negative territory. The market is look for them to “recalibrate” their two key pandemic tools of the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP), which allows for flexible asset purchases, and the Targeted Long-Term Repurchase Operations (TLTROs), i.e. cheap bank funding to maintain easy financing for companies while the economic impact of the crisis continues. PEPP is likely to be extended by at least six months until end-2021 and increased by some EUR 500bn to EUR 1.85tn so that aid can continue at the current pace until activity returns to pre-pandemic levels.

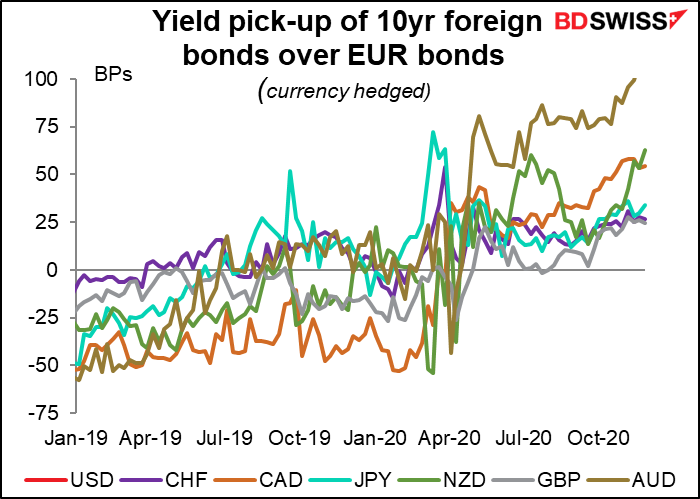

Impact on the currency: In general, quantitative easing measures such as these have more of an impact on the exchange rate than cutting interest rates by a small amount does. Cutting rates by 10 bps, which is all the ECB could do at this point, would have little impact even if it were deeper into negative territory. Further quantitative easing on the other hand could make foreign bonds even more attractive vis-à-vis EUR-denominated bonds and induce further portfolio flows out of euros, which might weaken the currency.

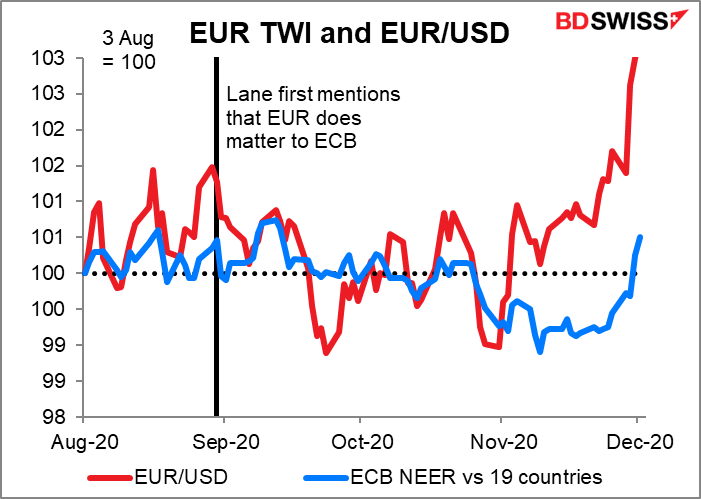

The question is, would the ECB care? ECB Chief Economist Lane started to voice his concern about the strengthening euro on 1 September, when EUR/USD first poked its nose above 1.20 (it hit a high of 1.2011 that day). He said then that while the ECB doesn’t target an exchange rate, the exchange rate does matter for them. We then heard more and more comments from ECB officials about how the exchange rate impacts inflation, which had just moved into deflation in August. The September ECB press conference codified their new “mantra” on the issue as “the Governing Council will carefully assess incoming information, including developments in the exchange rate, with regard to its implications for the medium-term inflation outlook.” This mantra was expanded in October to include “the dynamics of the pandemic, prospects for a rollout of vaccines and developments in the exchange rate.”

Since then though we have heard little about the exchange rate even as EUR/USD has remained consistently above 1.20 for the last several days. That’s for good reason: it’s more of a USD move than an EUR move. EUR/USD is 3.25% higher than it was at the beginning of August, but the broad EUR nominal effective exchange rate vs 19 of the Eurozone’s major trading partners is a mere 0.50% higher, and no higher at all than when Lane spoke. There’s no point in the ECB trying to fight a weakening dollar. I therefore think that the Council is not likely to emphasize the impact of these moves on the exchange rate. Without that additional emphasis – the signaling channel – I don’t think the move will have as much impact on the exchange rate as it would otherwise.

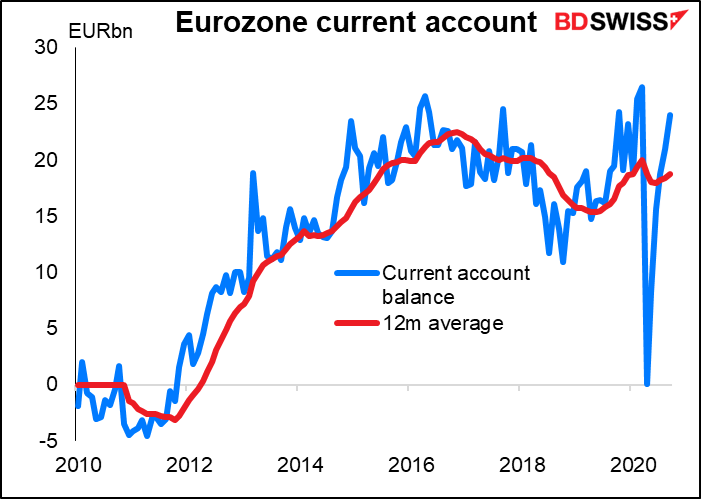

Furthermore, the Eurozone consistently runs a current account surplus. It’s hard to argue your currency is overvalued when you’re running a surplus. I therefore do not expect the ECB to emphasize the impact of these moves on the currency.

Bank of Canada: little to worry about

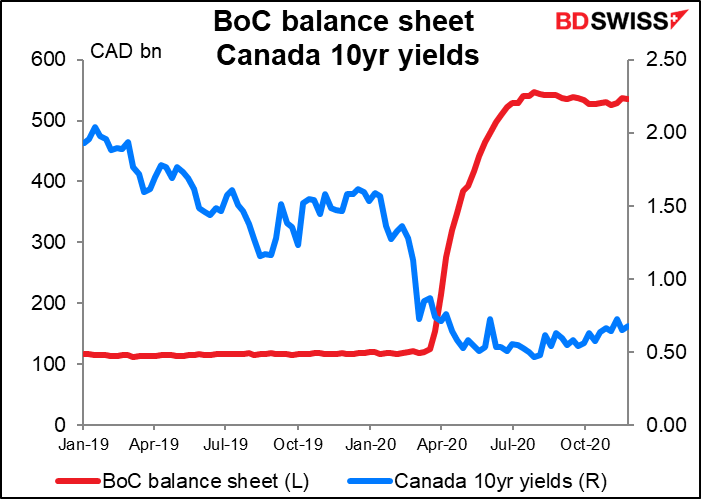

Compared to the ECB, Wednesday’s Bank of Canada meeting should provide relatively little in the way of news. I expect that like this week’s Reserve Bank of Australia meeting, they will simply review how the recent changes to their operations are going and comment on recent developments in the economy.

At their last meeting, in October, they kept rates steady but recalibrated their quantitative easing (QE) program: they shifted purchases more towards longer-term bonds, which they explained have a more direct influence on the borrowing rates that affect retail borrowers, while gradually reducing the amount of these purchases. The net effect should be to provide at least as much stimulus as before.

They’ll probably want to evaluate the impact of these moves for a few months, so I wouldn’t expect any further easing yet. At the same time, they said they do not anticipate raising the policy rate “until into 2023.” Net net, I anticipate an uneventful meeting with little impact on the market.

Other indicators: UK short-term indicator day, US CPI

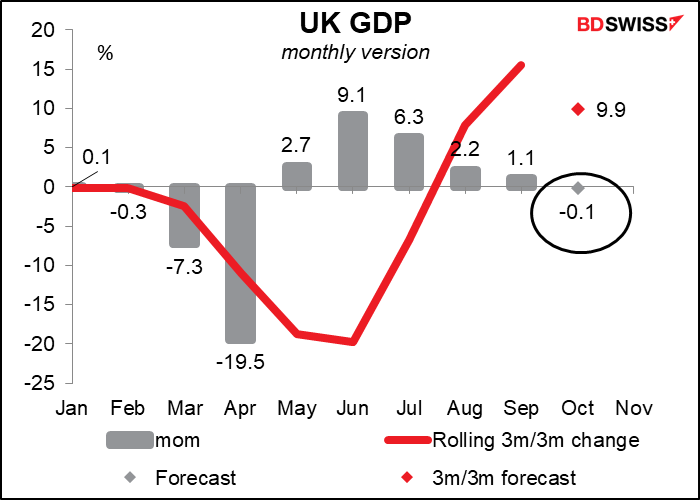

Thursday is short-term indicator day for the UK, when the country announces the monthly GDP, industrial & manufacturing production, and the trade balance.

I think the monthly GDP is the most important, even if it doesn’t rank highest in the Bloomberg relevance score (that would be industrial production). The forecast is for a small decline in GDP, as one might imagine as partial lockdown was reimposed in parts of the country during the month. The decline is likely to worsen in November.

I think the figures may cause a temporary flutter in GBP, but they’re only for one month in the past – the Brexit negotiations will affect the country’s economy for months and months ahead. Good or bad news on Brexit would therefore counter bad or good news on GDP.

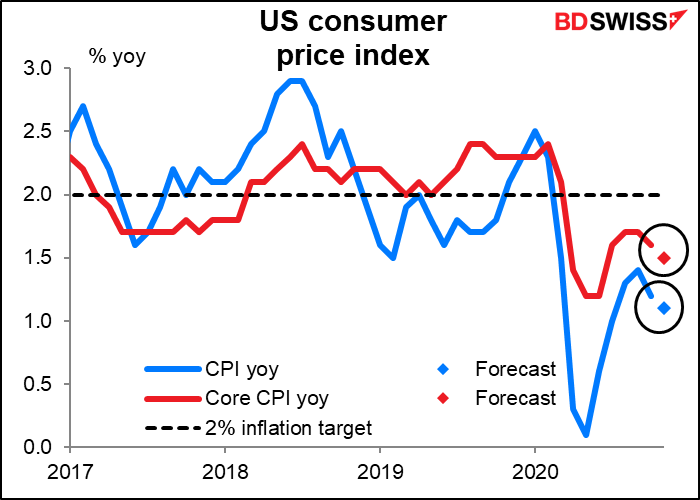

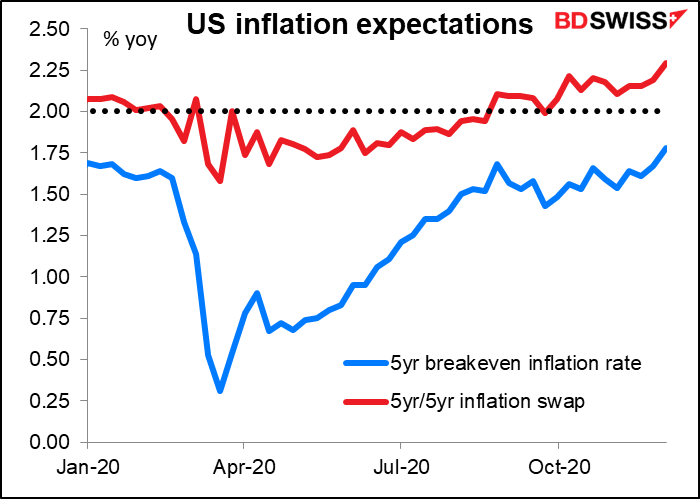

The US consumer price index (CPI) comes out on Thursday. Previously this was one of the biggest indicators of the month, but now, as I explained above, it’s not likely to elicit any policy change out of the Fed.

Expectations about a further slowdown in inflation could push against the recent increase in US inflation expectations. That would raise real yields and perhaps make the dollar more attractive.

Elsewhere, Germany announces its industrial production on Monday and ZEW Survey on Tuesday. Japan current account comes out Tuesday and machinery orders on Wednesday