Weekly Outlook

A Week to Remember

We’re finishing up a really busy week: three central bank meetings and a passel of important economic data. Now comes the deluge: the US general election, FOMC, Bank of England and Reserve Bank of Australia meetings, and the monthly nonfarm payrolls. What a week!

No doubt the election is the most important of all. The presidential election is pretty much considered over already – The Economist gives Biden a 95% chance of winning, while the political website FiveThirtyEight pegs his chances at 89%.

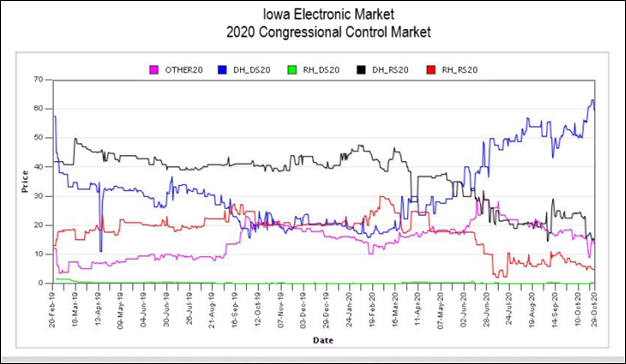

Although the odds of the Democrats retaking the Senate are nowhere near as certain, I think the market is assuming a “blue wave” that will put the Democrats in control of both Congress and the White House. What’s noticeable is that the market would no doubt welcome this all-Democrat administration, unlike in the past when Wall Street tended to lean Republican. It’s because with the Democrats, it’s virtually assured that the new administration will pass a fiscal stimulus package ASAP, either shortly after the inauguration (20 January) if not sooner (the new Senate will be seated 6 January). Any tax hikes however are going to come much much later, i.e. several years hence.

On the other hand, the Blue Wave isn’t a done deal by any means. Even if the Democrats win the vote, there is nothing in US law that says the people get to vote for the president. As bizarre as it may seem, a Republican state legislature could throw out the results and give the state’s electoral vote to Trump and it would be perfectly legal, albeit unprecedented and intolerable. Please see our Special Report on this question.

For those who’d like to know more about the possibilities in harrowing in detail, you can check out the 56-page paper, “Preparing for a Disputed Presidential Election: An Exercise in Election Risk Assessment and Management.” It says, in short,

The risk of a seriously disputed election depends in part on the preliminary returns available on election night, as well as the willingness of gerrymandered state legislatures to consider repudiating the popular vote, and the degree to which there develop genuine problems to fight over in court, or the ability to generate perceived problems that would give state legislatures cover for taking matters into their own hands.

Pennsylvania may be Ground Zero in this effort. From The New Yorker Magazine:

In Pennsylvania, even if Democrats win the popular vote, Republicans could contest the results, arguing that various procedural aspects are illegitimate. Court cases regarding the election could end up before the Supreme Court, which will be filled with Trump appointees and likely to rule in his favor. But Republicans don’t even have to win; all they have to do is stall. If the vote is not certified by December 8th, the Republican-controlled legislature could appoint electors, who would likely cast their votes for Trump.

Please don’t think this is just some theoretical question for law class. The Republicans in the Pennsylvania legislature started making preparations to do exactly this-+ but abandoned them when an outcry arose. But it could revive its plan immediately after the election, once their candidates are safe. Furthermore, several other states – Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Michigan – have similar conditions that would allow such shenanigans.

This is why the key issues are not only who wins, but also how long it takes them to win. The longer the count drags out, the greater the uncertainty. That’s sure to weigh on stocks and bonds even more than it did in 2000, when the Bush/Gore election went to the Supreme Court.

The thing to watch then is how well the candidates do in the “swing states,” those that could go either way, that report their results quickly. Trump has a limited route to acquire the 270 electoral votes necessary to win. If Trump loses several of these swing states, it will be impossible for him to win no matter what he and his myrmidons get up to elsewhere.

Florida (29 electoral votes) allows mail ballots to be counted before Election Day, which means we should get significant results from that state soon after the polls close at 00:00 GMT Wednesday. This is important because it will be almost impossible for Trump to win without winning Florida. Ohio (18) too counts its mail-in ballots ahead of time, so they should also be able to report shortly after 23:30 GMT. Texas (38) probably had limited mail-in votes (an excuse is required to vote by mail in Texas) so it too will report soon after its polls close at 01:00 GMT. Even more than Florida, Trump has no route to victory without Texas. North Carolina (15) estimates that it will report over 98% of ballots by election night.

For the Senate however we will have to wait to get the results state-by-state.

Impact of the election on the market

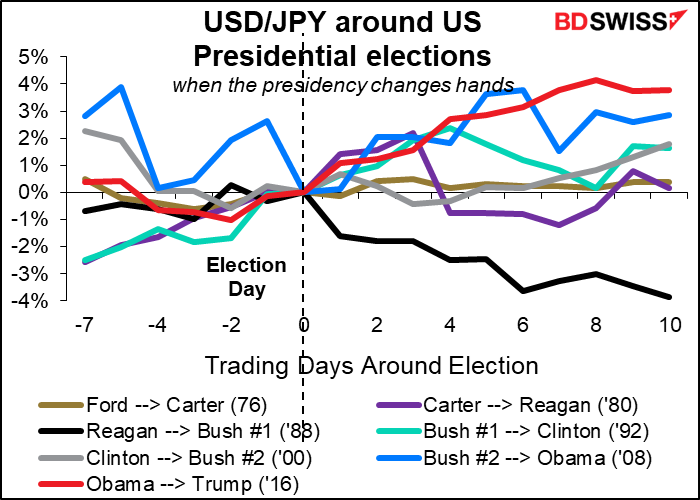

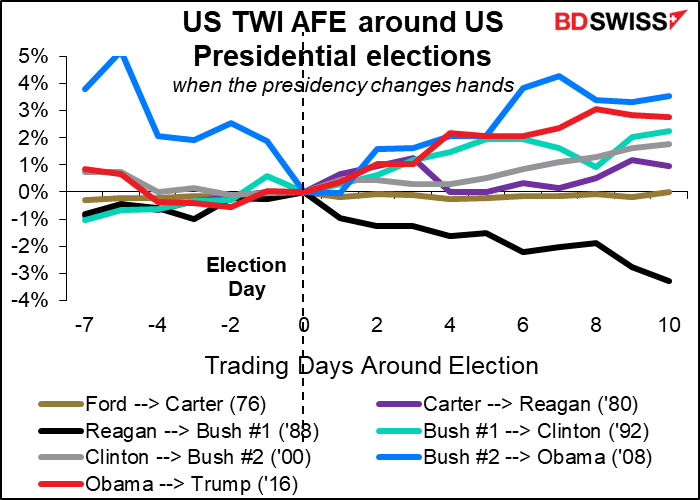

In the past, the dollar has tended to rise after the election. I just looked at the times when the Presidency changed hands.

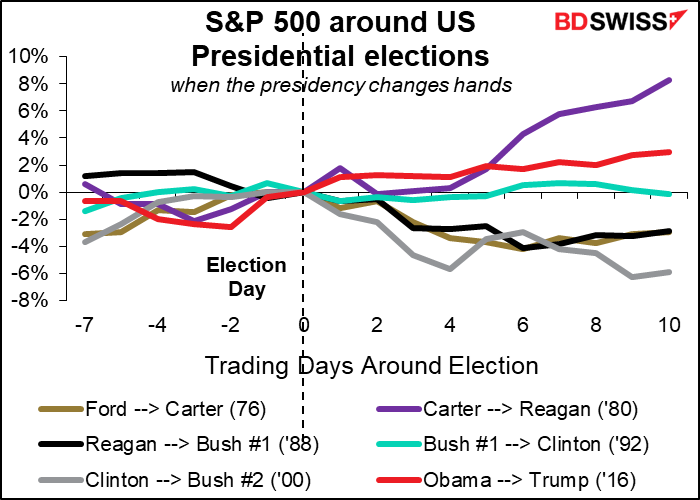

However, nowadays in the “risk-on, risk-off” world that we’re in, the course of the dollar is often determined more by the course of the stock market than by the course of the economy. That shows no particular pattern around elections.

Then let’s look at the five possible scenarios, with four different outcomes:

- A blue sweep: Democrats take the House, Senate and the White house. I believe this would be the most “risk-on” because it would result in the most fiscal stimulus. The Fed staff’s model of the US economy shows that an additional $2tn stimulus package, which is what the Democrats have suggested, could raise real GDP growth next year by about 5 percentage points, adding 3mn, and lower the unemployment rate by nearly 2 percentage points. No wonder even traditionally Republican-friendly Wall Street seems to be OK with this prospect. I think stocks would be higher and hence the dollar lower in this case.

-

- A blue tide. Democrats take the White House and retain the House of Representatives, but the Republicans retain the Senate. Some people in the financial world would prefer this alternative, as they lean Republican. But everyone knows too that this is a recipe for the current stalemate and inability to get anything done. There’s not likely to be much new fiscal stimulus if any, while the other key elements of the Biden agenda that could be implemented through executive orders or guidance on regulation are likely to be negative for near-term growth prospects I think this would be seen as neutral at best, probably disappointing. Stocks would probably fall somewhat and the dollar rise.

- Status quo Trump re-elected, Republicans retain the Senate, Democrats retain the White House. I think this would be seen as deeply negative. Frustrated with his domestic agenda, an increasingly demented Trump would spend more time fighting trade wars and seeking out domestic enemies. Congress would remain in stalemate. The virus would have spread unchecked until a vaccine is available, but so many Americans would refuse to take the vaccine that it would have little effect. Darkness and decay and COVID-19 would hold illimitable dominion over all. Stocks much lower, USD higher

- Republican sweep Republicans not only keep the White House and Senate, but also retake the House. This is virtually impossible (the website fivethirtyeight.com says 2% probability) so I’m not going to bother with it. Maybe I just don’t want to think about it.

- And the fifth? No one knows who won This I think is the biggest “known unknown,” i.e. the biggest risk that we know about. Counting the ballots goes on and on, disputes are dragged into the courts, protests and counter-protests mount, etc. Meanwhile nothing happens on fiscal policy. Much depends on the willingness of Republicans to “do whatever is necessary,” some of which might be legal but would certainly be unheard of, such as cutting off the count or even throwing out the results.

The huge crowds voting ahead of time makes me optimistic that this won’t happen, because the Democratic victory will be quick and decisive. However the brazen history of Republican Party power grabs – in particular, the way they pushed through the appointment to the Supreme Court this week just days before the election – makes me pessimistic that they might try anything. What we’ve learned over the last four years is that the bar cannot be lowered any further and the barrel has no bottom to scrape.

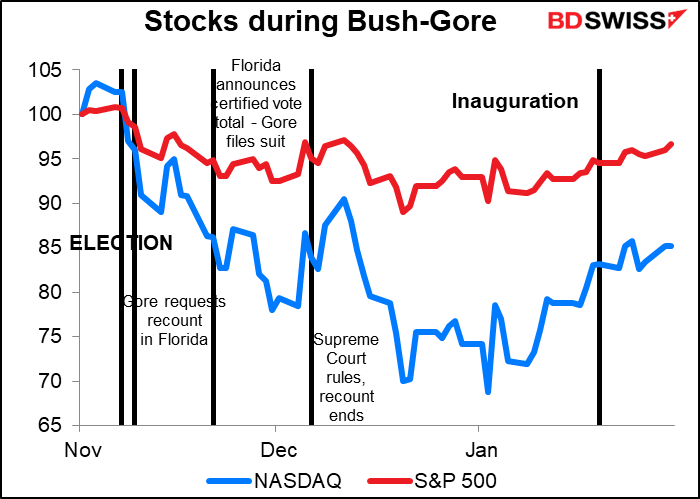

This is where the experience of Bush-Gore in 2000 becomes informative. Notice that the dollar kept falling even after the Supreme Court rendered its totally partisan and undemocratic ruling. Notice too how stocks kept falling (although we have to take into account that this was 2000, the year the internet bubble burst). I think the political and fiscal uncertainty on top of the recent medical uncertainty would be a deadly mixture for risk assets. Stocks would probably plunge.

Falling stocks could create a “safe haven” bid for USD, but I think the political uncertainty might prevent any “flight to safety” into the dollar. On the contrary, global confidence in the US political system might well be shaken, undermining the safe-haven status of the dollar. Certainly the Fed would have to step in with measures to “calm” the markets – that means further loosening, which would be negative for the dollar.

Other matters: FOMC, Bank of England, RBA, nonfarm payrolls

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the rate-setting body of the US Federal Reserve, meets the day after the election. There hasn’t been an FOMC meeting in an election week since 1984. Looking back at the minutes to that meeting, the Committee didn’t hesitate to take action (they loosened policy a bit) the day after the election. However if I remember correctly, back in those days the Fed didn’t announce its decisions, but rather market participants had to deduce them from the Fed’s subsequent actions in the market. Hence the-then glamorous occupation of “Fed watcher.” Nowadays of course transparency is the name of the game and any decisions will be instantly apparent and explained in depth & detail in the Chair’s press conference.

Listening to a number of Committee members recently, they all seem to be singing the same song, which I mentioned in my Weekly Outlook of 25 September: Please sir, I want some more.” Some more fiscal stimulus, that is. I doubt if they would make any changes in policy just a few weeks before they might actually get what they’ve been pleading for. That would be a waste. They could downgrade their outlook somewhat, although it’s pretty bleak already.

In their forward guidance, they said they would be “prepared to adjust the stance of monetary policy, if appropriate” and that they would take into account “readings on public health, labor market conditions, inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and financial and international developments.” I could imagine that they add something more specific about fiscal developments into their criteria. The Fed tries to stay out of direct involvement in politics though so we can’t expect too much along those lines.

We’ll probably have to wait for the press conference to hear what the Committee members are thinking nowadays about further measures, particularly concentrating purchases in the long end of the market (as the Bank of Canada announced this week that it would do) or full-blown yield curve control (which I don’t expect yet).

Bank of England: raising the ceiling for asset purchases

The Bank of England is in a similar position to the Fed in that the denouement of the Brexit process may well come at the EU summit the following week. If they loosen now but find that the markets are rocked by the collapse of the talks a few days later, what could they do?

However, there’s long been the expectation that the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) might do something at the November meeting. Indeed, in my outlook to the September meeting, I wrote that nothing was expected then but rather “The excitement is likely to come in November…A number of forecasters are expecting some move then or in December.”

Even more so now than in September. The August Monetary Policy Review (MPR) was forecasting for a “V”-shaped recovery, with output returning to pre-pandemic levels next year. Things were even better at the September meeting, when the MPC said “recent domestic economic data have been a little stronger than the Committee expected at the time of the August Report.”

Alas that’s no longer the case. On the contrary, the market sees Britain’s output still 2.9% short of Q4 2019 levels by 1Q 2022, worse even than the Eurozone at -1.1%. US output on the other hand is expected to return to Q4 2019 levels by Q3 2021.

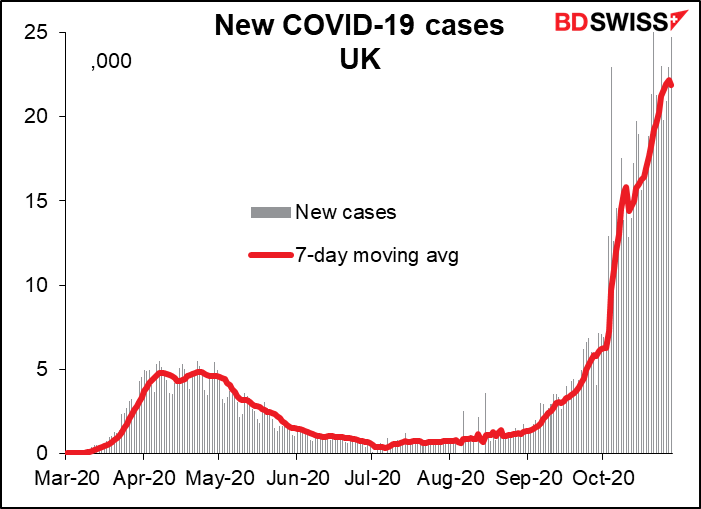

Meanwhile the virus is exploding and more restrictive measures are being imposed. That’s going to be a further drag on growth and inflation,

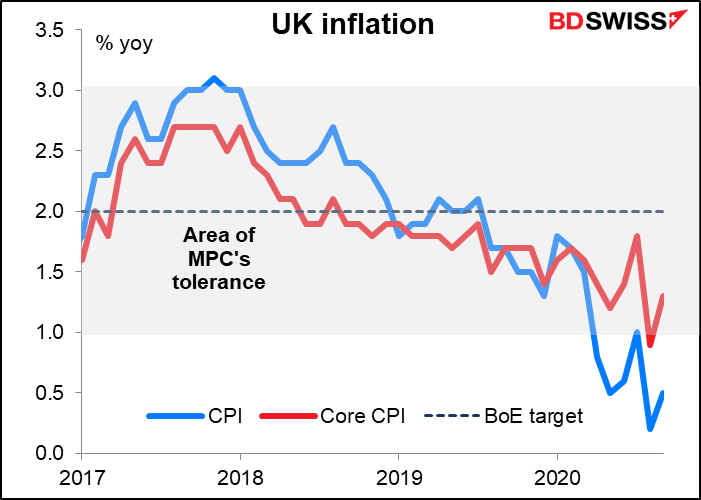

Headline inflation is below the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) range of tolerance, and the MPC calculates that two weeks of social distancing measures cuts 75bp off inflation in the subsequent quarter.

The market was expecting that with the new Monetary Policy Review coming out at next week’s meeting, the BoE would probably make some changes to its operations, just as the European Central Bank hinted this week that it would use the revisions to its forecasts in December as the justification for further loosening. Most likely, the BoE will increase the ceiling on its Asset Purchase Facility, because at the current pace it will run out of room by 21 January. The question is, by how much? I think the market will be waiting to see the size of the “top-up” to judge the BoE’s stance. GBP 50bn would probably be the minimum; GBP 100bn would be seen as aggressive, I think.

I don’t expect them to lower rates. Although the market is expecting lower rates at some point, I think they’ll want to get the response of the banks on the operational feasibility of negative rates before they decide anything on rates, and they’ll only get that on 12 November.

Of course, whatever the BoE does is secondary to any Brexit announcements. Any news about a breakthrough – or a final, real, this-is-it breakdown in the talks – would be of much greater importance to the UK economy than an extra GBP 50bn of quantitative easing.

Reserve Bank of Australia: Antipodean “recalibration”

We got some big hints about further RBA easing for some weeks now. On 15 October RBA Gov. Lowe gave a speech entitled “The Recovery from a Very Uneven Recession.” In this speech he said, “In terms of unemployment, we want to see more than just ‘progress towards full employment’. The Board views addressing the high rate of unemployment as an important national priority. Consistent with our mandate, we want to do what we can do, with the tools we have, to ensure that people have jobs.” (emphasis added)

Back in 2019, the RBA revised down its estimate of “full employment” to be an unemployment rate of around 4 ¾%. With the rate currently 6.9%, there’s a long way to go. We infer from that that they’re going to do something soon.

Possible measures include:

- A cut in the Cash Rate and three-year government bond target to 0.1% from the current 0.25%. This would seem to be the most certain move. (FYI the market is discounting rates at 0.05% by year-end).

- The introduction of a yield target for the five-year government bond. The RBA recently changed its thinking about inflation to be more like the Fed’s, namely that it won’t start raising rates until it sees actual inflation rising, rather than moving preemptively based on forecast inflation. Shifting the bond yield target further out the curve from three years to five years would be consistent with their estimate for how long it might take to get inflation up to the desired level and therefore how long their current easy policy is likely to be in place

- The introduction of a large scale asset purchase program in the longer end of the curve, past five years’ maturity. While it seems likely that some kind of program will be announced, the size and the maturity of the bonds to be purchased are uncertain.

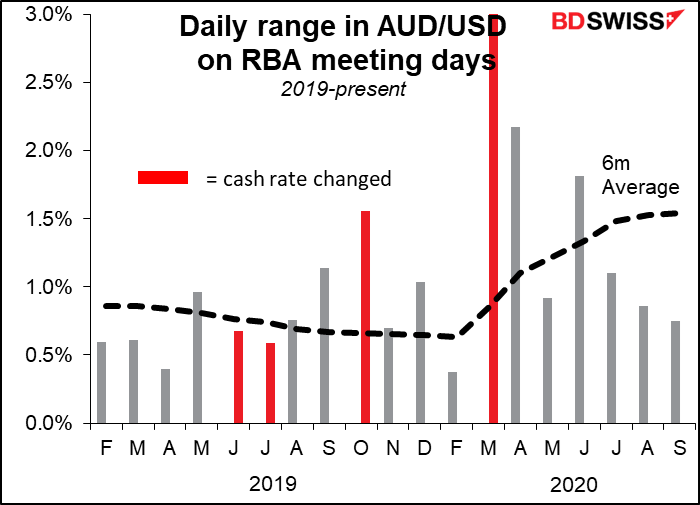

Market impact: could be big: We have seen increased volatility on RBA days when they’ve changed rates. Then again, sometimes not, when the move was well telegraphed. Recently RBA days have had distinctly less-than-usual volatility. In this case, I think some move(s) is/are expected. The question is whether the RBA can beat estimates. If they can, we could be in for a volatile day. I think the moves are likely to weaken AUD.

Nonfarm payrolls – not the big thing this month

Usually the monthly nonfarm payrolls (NFP) are a Very Big Deal, but I think recently the weekly jobless claims are taking some of the shine off the NFP.

In any case, I think the NFP figure is going to be disappointing. Although it’s expected to show a continued rise in the number of people working, the increase is forecast to be down for the fourth month in a row, showing a slowing recovery.

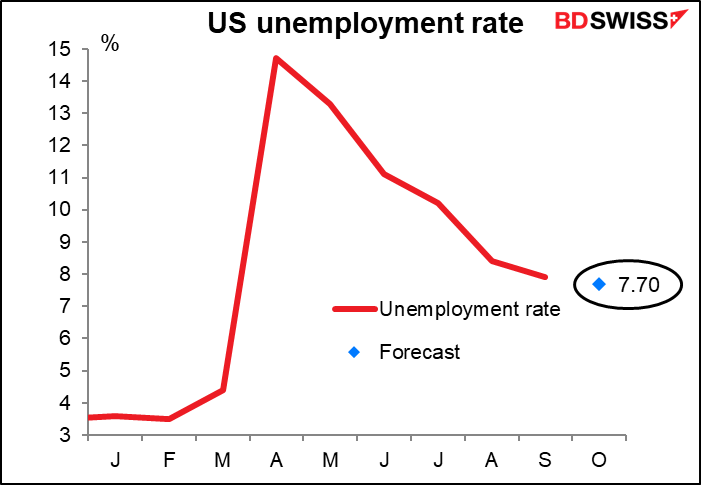

The unemployment rate is forecast to fall only 20 bps to 7.7% from 7.9%. This is still unacceptably high. And of course the U-6 unemployment measure, which includes underemployment and those not actively looking for a job because there’s no hope, is a much higher 12.8%. Still a bad situation, and getting better at a slower and slower pace.

The question is, will the market see the glass as half-empty – a slowdown in the pace of improvement – or half-full – continuing improvement? I suspect the former and that this will be seen as negative for risk and therefore positive for the dollar.

Of course, if Trump concedes or resigns on Friday, then that will take precedence.

Other indicators

Other things fade in importance.

The Brexit talks will be ongoing during the week, but we didn’t get much news this week and I don’t know if we’ll get any more next week. They are deep into sensitive, secret talks and there isn’t as much leaking as usual.

The final purchasing managers indices (PMIs) for those countries that have preliminary versions, and the one-and-only version for those that don’t. Monday is manufacturing, Wednesday is services. The US Institute of Supply Management versions come out at the same time, as usual.

German factory orders (Thursday) and industrial production (Friday).