Weekly Outlook

Digital time in Europe

One of the highlights of the coming week will be a web-based conference held by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS): “Innovation Summit 2021: How can central banks innovate in the digital age?” This summit should interest all of you folks who are cryptocurrency enthusiasts as the main topic will be central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). Basically, CBDC: yes or no, and if yes, how?

Hear from global leaders on key issues around cross-border and retail payments, central bank digital currencies, banking and the new digital ecosystem, decentralised finance, data, analytics, AI and cloud technologies as well as cultural and organisational changes that may be needed within central banks to meet the challenges of this digital age.

There will be a glittering array of top-level speakers, including Fed Chair Powell; European Central Bank (ECB) President Lagarde; her arch-nemisis, Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann; former Bank of England Gov. Carney; and the President of Microsoft, Brad Smith. You can register here to watch it for free. It runs Monday through Thursday.

What is a central bank digital currency? Currently, central banks provide two kinds of money to the economy. One is cash, which is used largely for retail transactions. The other is electronic central bank deposits, also known as reserves or settlement balances, which are used exclusively by qualifying financial institutions. CBDCs would be a third kind of central bank money: a digital payment instrument, denominated in the national unit of account, that is a direct liability of the central bank.

Before you get too excited, let me point out that CBDCs are nothing like Bitcoin or the ghastly Dogecoin. You are never going to get rich buying a CBDC, any more than you would by stockpiling dollar bills or euros. The purpose of CBDC is to facilitate transactions, not to enable people to get rich by HODLing them. That’s because CBDC will be designed to be currencies used for transactions, not assets to make a killing off of. Two fundamental requirements for a currency are that it be a stable store of value and a unit of account. An asset whose price varies a lot – even if by “vary” we mean “rise” – is by definition not a stable store of value and can’t be used as a unit of account.. As Fabio Panetta, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, said in a recent speech (Evolution or revolution? The impact of a digital euro on the financial system), “A digital euro should be an efficient means of payment, domestically and internationally. But crucially, in order to preserve stability, it should be designed in a way that prevents it from being used as a form of investment.”

According to the BIS, interest in CBDCs among central banks has grown in response to changes in payments, finance and technology, as well as the disruption caused by Covid-19. A BIS survey earlier this year found that 86% of central banks are actively researching the potential for CBDCs, 60% were experimenting with the technology and 14% were already deploying pilot projects. In the next three years, central banks representing about 20% of the world’s population are likely to issue a general-purpose CBDC.

From BIS Working Papers No 880: Rise of the central bank digital currencies: drivers, approaches, and technologies

Who are the leaders in this? So far it’s the Bahamas, with their digital Bahamian dollar, the sand dollar, already in widespread use. China, which started researching the idea in 2014, began testing an e-RMB last year. Sweden has started the first trial of its digital-krona project, the e-krona. The ECB will soon receive the initial results from a trial and then decide whether to pursue the idea. The Fed, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan are studying the issue but haven’t taken any decisions yet. Meanwhile, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority and the Bank of Thailand have been joined by the People’s Bank of China and the Central Bank of the UAE in the Multiple Central Bank Digital Currency (m-CBDC) Bridge Project to support multicurrency payments at the wholesale level for cross-border payments.

My impression is that the BIS is fairly enthusiastic about CBDCs and several emerging market (EM) countries are well on their way to implementing them. It’s easier for the EM countries because their young populations (more tech-savvy) and relatively high interest rates (higher opportunity cost of holding cash) make CBDCs a more attractive proposition than in countries with older populations and zero interest rates. Also, the central banks in the major industrialized economies are still mulling over the pros & cons. Those pros & cons, as Panetta laid out in his speech, are as follows:

Paradoxically, a digital euro may prove too successful. If it is not properly designed, its main strengths – safety and liquidity – could affect monetary and financial stability on three fronts: first, financial intermediation and capital allocation in normal times; second, financial stability in times of crisis; and third, the functioning of the international financial system.

Financial intermediation and capital allocation in normal times: The concern here is that if everyone could have an account at the central bank and use the CBDC to pay their electric bill etc., why would they need to use a bank? The banks would lose deposits and credit creation would slow. Banks would have to charge more to make up for lower volumes, further dampening growth. At the extreme, the financial system as currently structured might collapse. Panetta solves that by saying “Financial intermediaries – in particular banks – would provide the front-end services, as they do today for cash-related operations. We would provide safe money, while financial intermediaries would continue to offer additional services to users.” This is how it’s done in the Bahamas, for example.

Financial stability in times of crisis: the problem of “flight to safety” would be even more pronounced in times of crisis, when people would have a big incentive to move their money out of the commercial banks. These “digital runs” could destabilize the financial system. Indeed the very existence of the CBDC might make such runs more frequent than they are today.

The functioning of the international financial system: a digital euro accessible to non-residents could make the single currency more attractive to foreigners. However, that might also leave the Eurozone vulnerable to large swings in investment in and out of the currency (a problem that EM countries have had to deal with for ages, but never mind). On the other hand, allowing global access to a reliable, easy-to-use hard currency could cause transactions in less reliable currencies to wither away, resulting in the “digital dollarization” of smaller countries with less stable monetary systems.

On the other hand, CBDCs do offer many advantages and possibilities to central banks. For example, they would allow widespread access to central bank money when cash is in decline; provide an easier way to distribute money in remote areas or during natural disasters; increase the diversity and efficiency of payment networks; encourage financial inclusion (get more people into the banking system); improve cross-border payments; facilitate fiscal transfers; and enable innovations in monetary policy, such as changing interest rates throughout the economy instantly or even implementing negative interest rates by programming money to expire after a certain time.

The question that many readers may have is: what impact, if any, will CBDCs have on cryptocurrencies? And here’s where I may get into hot water. I think the rollout of CBDCs could be the end of the cryptocurrency boom. Here’s why.

The reason is embedded in their very name: cryptocurrencies. Cryptocurrencies are called that because one of their main selling points is the ease of using them for transactions. Instead of having to go to the bank and pay a big fee to change money, wait for T+2 settlement, then pay another fee to have the money transferred (a fee that depends on the amount of money being sent, as if it requires more work to send $1,000 than it does to send $100), you can do it all from an app on your phone instantaneously and in some cases (almost) anonymously. As a result, enthusiasts said, the world would gradually move away from using dollars and euros and pounds in their day-to-day life and the financial system would be decentralized and democratized.

Putting aside the fact that it will never happen since most governments will only accept their own currency as payment for taxes, we have to ask: what happens to private-sector commercial cryptocurrencies when an even better model comes in? Why would anyone use a hack-prone website to buy a token of uncertain value for any day-to-day purpose when the government is supplying a reliable, insured version that’s of universally recognized value? At least, why would they buy it to use it for transactions when a digital dollar or euro is available?

We then get to the nature of the problem. Cryptos like Bitcoin and Dogecoin aren’t cryptocurrencies – they’re crypto-assets. People aren’t buying them to make it easier to pay for the pizza that they ordered, they’re buying them in the hopes that they appreciate. But here’s the point I’ve never understood: why should their price go up if no one has any real use for them? That’s the existential question that the rollout of CBDCs will expose and why I think CBDCs could spell the end of the crypto-asset boom.

Other events this coming week: EU leaders’ meeting, preliminary PMIs, US personal income & spending, UK employment

Digital transformation will also be one of the topics at the European Council meeting Thursday and Friday. (The European Council consists of the heads of state or government of the member states, together with the President of the European Commission.) EU leaders discussed the digital transformation at their meeting in October, at which time they asked the European Commission to create “a comprehensive Digital Compass which sets out the EUʼs concrete digital ambitions for 2030.” That vision for a “digital future for Europe” will be revealed at this coming week’s meeting, including work on digital taxation. (Does that mean people with more digits will be taxed higher? Stay tuned to find out!)

Other topics that they’ll discuss include:

● COVID-19: The roll-out of vaccines, the epidemiological situation, and the coordinated response to the pandemic crisis.

● 2021 European Semester (aka Budget): The priorities for the 2021 European Semester. Leaders will endorse (or not!) the recommendation on the economic policy of the eurozone.

● Eastern Mediterranean: The Eastern Mediterranean and a report on EU-Turkey relations.

● Russia: a strategic debate on the relations with Russia.

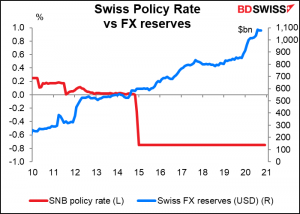

There’s also one central bank meeting during the week, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) on Thursday. There’s not much point in discussing their likely behavior in depth. They haven’t made any substantial changes to their policy since January 2015 and I don’t expect any changes at this quarterly meeting either.

There are a also a few Fed officials speaking during the week: NY Fed President Williams (V) three times, SF Fed President Daly (V) twice, and Chicago Fed President Evans (V) and St. Louis Fed President Bullard (NV) once each. That’s just with regards to the speeches about the market; there may well be other speaking engagements that aren’t concerned with the economy and policy. We may get more clarification around the Fed’s view on the recent rise in rates. It will be especially important to hear if they push back at the market’s continued pricing in of a rate hike in 2023 despite the FOMC’s continued insistence that it just ain’t gonna happen.

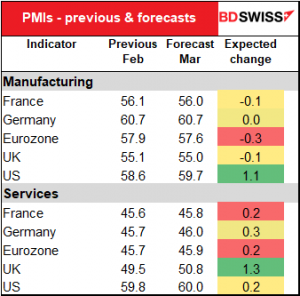

As for the indicators, the highlight of the week will be the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) from the major industrial countries on Wednesday.

In manufacturing, the market is looking for a small decline in Europe and the UK but a substantial rise in the US. Since the manufacturing PMIs are already at fairly high level, I don’t think these small declines will be significant. However the large rise in the US could be if it reinforces the view that demand is heating up in the US, which could bring higher inflation.

In the service sector, the more troubled part of the economy, the outlook is good – all the areas for which forecasts are available are expected to show a rise, which is impressive considering the lockdowns in many places. The UK is forecast to return to above the 50 “boom-or-bust” line, which could be a big positive for GBP. The US is forecast to rise further from its exceptionally high level.

Remember that the news organizations have just started collecting forecasts. These “consensus forecasts” are subject to considerable change over coming days as more and more forecasters contribute.

There are a number of major US indicators coming out.

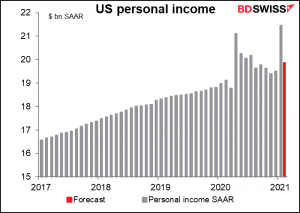

After the huge 10% jump in personal income in January, thanks to the pandemic checks, incomes are expected to fall by 7.5% mom in February. That would still leave them 4.3% higher than the pre-pandemic level. Another round of checks should be coming in March, no? So this should be encouraging.

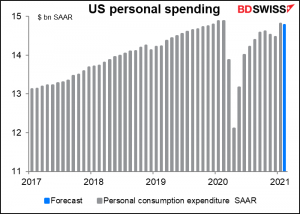

Spending is also expected to be down, but not by as much, just -0.2%. That would put spending only a little (-0.6%) below pre-pandemic levels.

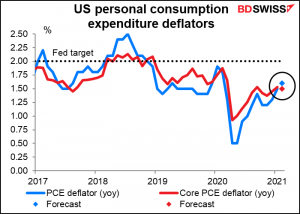

The personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflators, which are released at the same time, are expected to show inflation accelerating a bit at the headline level but remaining at the same pace in the core measure. This wouldn’t be a worry for the Fed, which as we saw yesterday is forecasting that PCE inflation will surpass 2.4% yoy this year. It would however mean lower real rates, which could be negative for the dollar.

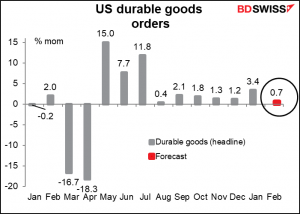

US durable goods orders, on Wednesday, are expected to rise further even after the unusually large increase in January. The figures point to another strong quarter for business investment, which should be good for stocks if not for the dollar.

Other US indicators coming out include existing home sales on Monday, new home sales and the Richmond Fed index on Tuesday, and the third and final revision of Q1 GDP on Thursday.

It will also be a big week for UK indicators, with employment (Tue), CPI (Wed), and retail sales (Fri). Nowadays I’d say the employment data is more important than the CPI data, because a) CPIs are rising everywhere due to higher oil prices and base effects, and b) the health of the labor market is an indicator of future growth prospects, and growth is what’s concerning the market now. The unemployment rate is expected to rise. This shouldn’t surprise anyone though because the February Monetary Policy Report forecast that unemployment would rise over the next couple of quarters. Yesterday’s Bank of England Monetary Policy Summary pointed out that the near-term rise in the unemployment rate “will be more moderate than suggested by the MPC’s February Report projections,” thanks to the extension of the Government’s employment support schemes, but it’s still likely to be higher. A rise should therefore already be in the price, but I wouldn’t ignore the possibility that the market has a knee-jerk reaction anyway and that the figure is negative for sterling.

The UK inflation data is forecast to show headline inflation nudging up slightly but still below the Bank of England’s band of tolerance. This certainly would not qualify as “significant progress” toward “achieving the 2% inflation target sustainably” and so wouldn’t give the Bank of England any reason to reconsider its stance.

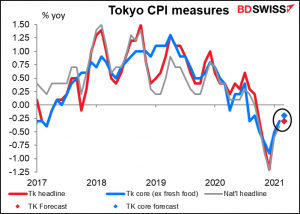

Japan will also release the Tokyo consumer price index (Fri) which is more closely watched than the national CPI. Although the core CPI, the one that people focus on the most, is expected to tic up a bit, it’s expected to remain in deflation for the eighth consecutive month. With the BoJ’s new policies to help banks out if interest rates move lower, will that spark thoughts of further BoJ easing? I doubt it, but you never know.