Weekly Outlook

Oliver Twist: the New Model Central Banker

I don’t know if it was in the original Dickins book, but Oliver Twist’s famous line from the movie, “Please sir, I want some more” might as well be the motto of every central banker nowadays. We heard this several times during the week from Fed Chair Jerome Powell, who begged every Congressperson he could find to get on with it and spend more money, presumably paid for by issuing bonds that the Fed would then purchase.

“The power of fiscal policy is really unequaled by anything else,” Powell said on Tuesday. The recovery would move along faster “if there is support coming both from Congress and from the Fed,” he said Wednesday.

Other members of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) echoed his words. “This is a time where a delay in fiscal policy, I think, is much more economically impactful than what we (the Fed) do because to be honest, the long rate is already quite low,” said Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren. “There is a limit to how low we can get it.”

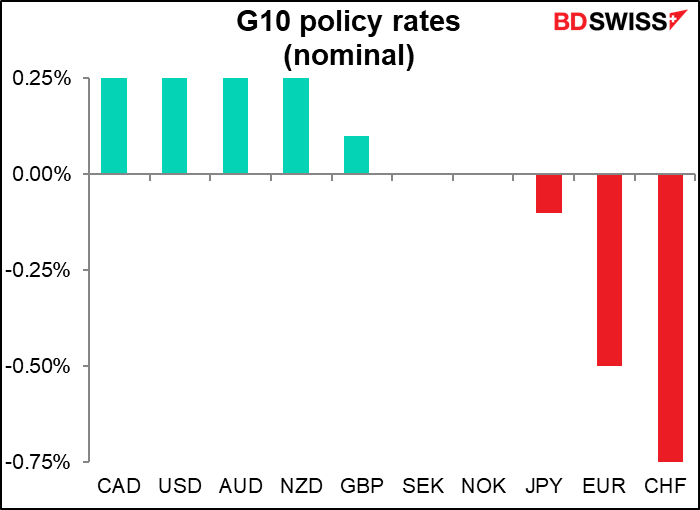

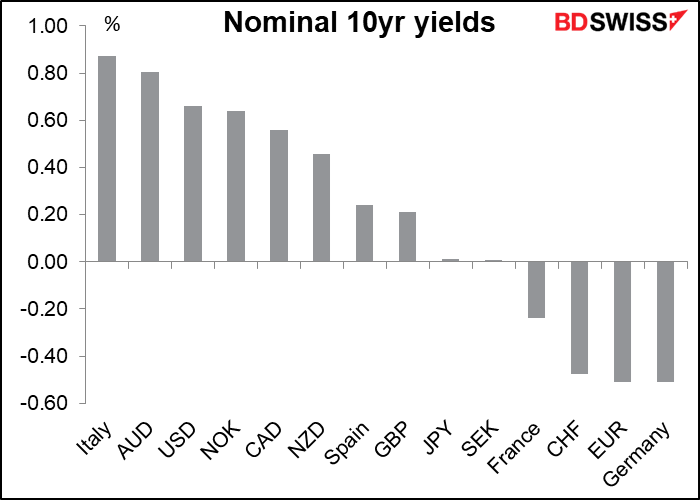

This view isn’t unique to the US. It seems to be the general view from central banks around the world, because they’re all in the same boat. Monetary policy is reaching its limits. With policy rates more or less at zero across the G10 and few 10-year bonds yielding even 1%, it’s hard to think of what else central banks can do to help boost their economies. Fiscal policy has to take over from here.

During the early days of quantitative easing in Japan, people often asked, what’s the purpose of flooding the banks with reserves? The answer was the “ice cube tray theory” of monetary policy. With an ice cube tray, you pour water into one square and it overflows, eventually filling up all the squares. The idea was that QE would accomplish something similar: by flooding the economy with money, eventually it would find its way to everyone who needed it.

Now, with every central bank enacting a dizzying variety of government-guaranteed lending programs, the “ice cube tray theory” is being tested to its ultimate. And what people are finding is that some problems go deeper than that. “Many borrowers will benefit from these programs, as will the overall economy, but for others, a loan that could be difficult to repay might not be the answer,” said Powell. “In these cases, direct fiscal support may be needed.” Eventually the bankers run out of tools.

While there are a few more tools in the toolkits, they are extreme. The Bank of England and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) are making operational preparations for negative interest rates, for example, although the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) says their record is “mixed.” And then, as I discussed last week, there’s the ultimate: foreign exchange intervention.

This idea is hardly new. It cropped up in the minutes to one of the Bank of Japan Monetary Policy Committee meetings back in October 2001. An anonymous member — no doubt the iconoclastic Nobuyuki Nakahara – contended that

….the Bank should examine ways to purchase and manage foreign bonds, since the member considered that purchases of foreign bonds as a means of quantitative easing were possible within the framework of regular business of the Bank prescribed in Article 33 of the Bank of Japan Law.

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) has been doing this for years, and Thursday reaffirmed that it would keep doing it. “In view of the fact that the Swiss franc is still highly valued, the SNB remains willing to intervene more strongly in the foreign exchange market, while taking the overall exchange rate situation into consideration.”

The RBNZ Wednesday said the idea “remains under consideration” although it is not the next step it would take if it decides to escalate policy, nor even the second step.

We also heard this week from RBA Deputy Gov. Debelle, who outlined “possibilities for further monetary policy action should the Reserve Bank Board decide that it is warranted.” Among the “potential policy options” that he mentioned was – wait for it — foreign exchange intervention. Although he registered several objections to the idea, he added, “That said, a lower exchange rate would definitely be beneficial for the Australian economy, so we are continuing to watch developments in the foreign exchange market carefully.”

He also mentioned several ways in which spillovers from the RBA’s current monetary policy help to lower the exchange rate. For example, he noted that the banks have reduced their offshore wholesale funding by an amount “of a very similar size” to the amount that they’ve taken up from the RBA’s Term Funding Facility. That implies less foreign buying of AUD. Also, while the RBA targets the 3-year bond yield because of its role as a domestic benchmark, the lower interest rate does have an effect on portfolios that would tend to weaken the exchange rate. When the Bank buys a longer-term bond in exchange for cash, “This incentivises investors to switch into other assets, including potentially foreign assets, to get that duration exposure,” he explained (emphasis added.)

What really caught my eye in Debelle’s speech though was that he said they are watching developments “carefully.” Where have I heard that before?

Oh yes, ECB President Lagarde Monday said, “the uncertainty of the current environment requires a very careful assessment of the incoming information, including developments in the exchange rate, with regard to its implications for the medium-term inflation outlook.” And last week ECB Executive Board member Fabio Panetta said “In light of the current outlook for inflation, we need to remain vigilant and carefully assess incoming information, including exchange rate developments.” (He even added “vigilant,” another famous ECB code word!)

How long will it be before competitive devaluations – either directly through bond purchaes or indirectly through spillovers from domestic monetary policy – become the next extraordinary monetary policy to become ordinary?

And when they do, will the US stand for it? But that’s a question for another week.

The coming week: NFP, CARES Act negotations, US presidential debate, tankan, EU inflation, Brexit talks

The last week of the quarter and the first week of the month coincide, bringing us a number of closely watched indicators.

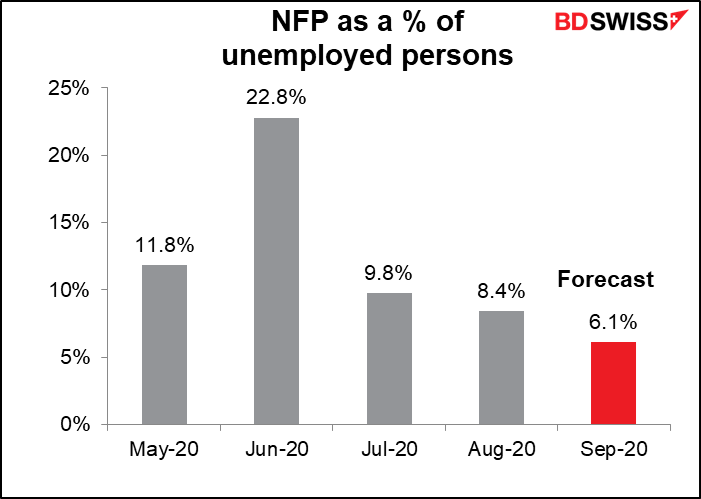

Of course the US nonfarm payrolls is the star of the show. They’re expected to be disappointing, which isn’t surprising as the weekly jobless claims figures have been disappointing, too. The third consecutive decline in payrolls is likely to be negative for the dollar, in my view. The only question is whether people are perhaps braced for a fall in jobs and therefore any rise could be taken as a positive.

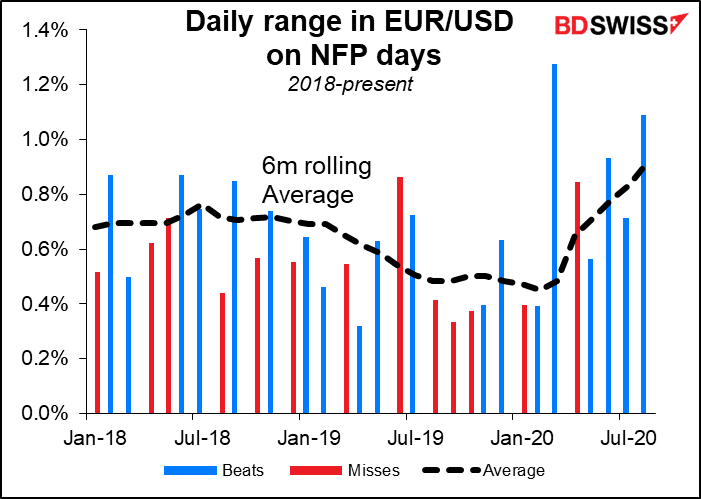

In any event, the announcement generales a lot of heat but not much light. The market is often less volatile than usual on NFP days regarldless of whether the figure beats or misses expectations.

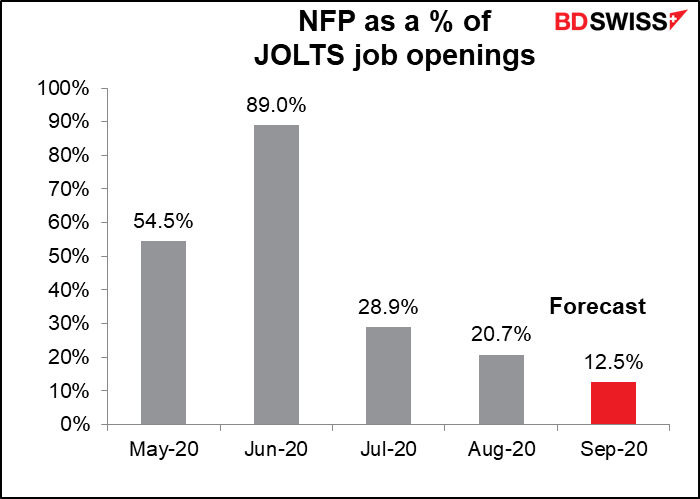

As for this month’s data, not only is the absolute number of new jobs expected to decline but also the number of new jobs as a percent of the number of unemployed persons in the previous month is expected to decline. In short, the figures are expected to show that the improvement in the job market is slowing.

The number of people getting jobs has also fallen relative to the number of jobs available.

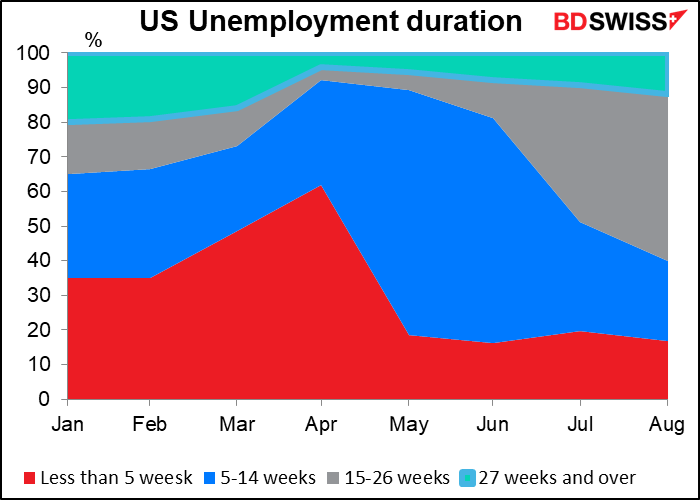

One possible reason is a mismatch between the jobs available and the people looking for jobs. Many of the people thrown out of work are in the service sector, which has not recovered yet. These people may not have the education necessary to qualify for the jobs that are available.

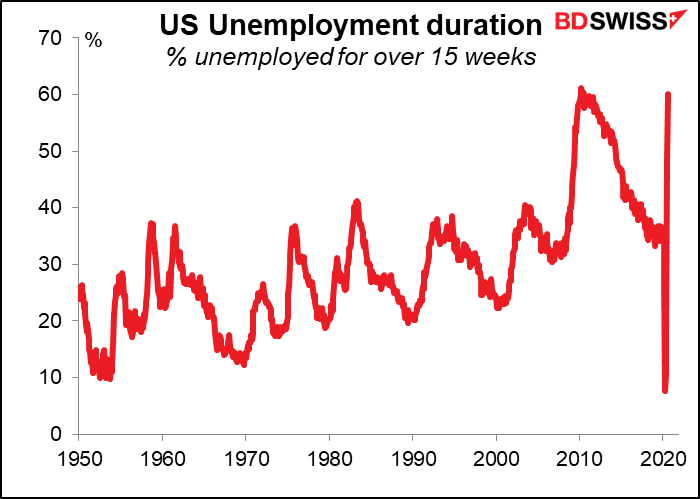

The mismatch between the skills available and the jobs available has caused the duration of unemployment to increase dramatically. The percent of the unemployed who’ve been unemployed for more than 15 weeks is near a record high (60.1%, vs the record high of 61.1% in Aprl 2010)

Those people who were thrown out of work earlier in the year are finding it hard to find a new job. People who’ve been unemployed for 15-26 weeks, the grey area that’s now the largest group, lost their jobs between mid-February and mid-May.

This is why Congress’ failure to come up with a new CARES Act is such a disaster. It’s government money that’s keeping millions of Americans afloat Without that lifeline, they’re going to sink into poverty, with a knock-on effect throughout the economy. Remember, my spending is your income. If people don’t have money to spend, then other people’s incomes will suffer. The economy will spiral down and it will be very very hard indeed to get it going again as companies close their doors permanently and jobs disappear for good.

Both sides are talking about restarting negotiations on a new package, but it’s not clear to me that they’ll be able to bridge the gap. The HouseDemocrats have reduced their ideas to $2.4trn, down from over $3.2tn, but the Senate Republicans have already rejected a $1.1tn plan. The Washington Post reported that Pelosi is under increasing pressure from vulnerable lawmakers to make a deal, but the time is so limited – Congress is supposed to adjourn at the end of next week. These negotiations, if indeed there are any, will be the major focus of attention next week. Any signs of an agreement would be likely to set off a “risk-on” mood, while failure would have the reverse impact.

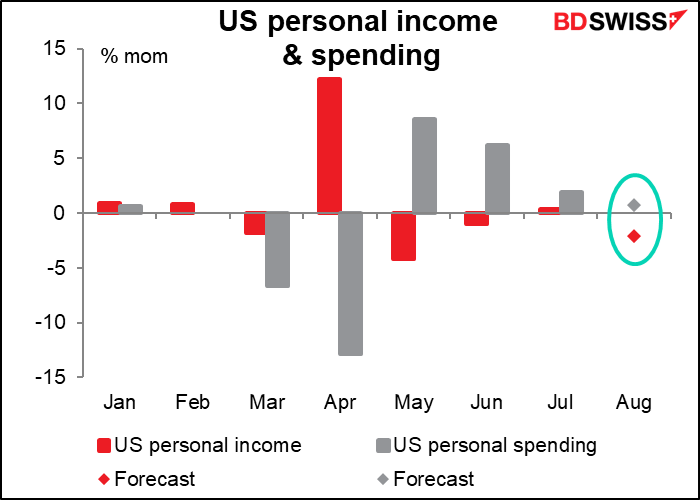

Speaking of incomes, Thursday we get the US personal income & spending data. It’s expected to show a 2.1% mom fall in incomes and a much smaller (+0.7%) rise in spending than the previous month (+1.9%), which makes sense. This is thanks to the decline in payments from the government. No wonder the FOMC members were all pleading for Congress to get their act together!

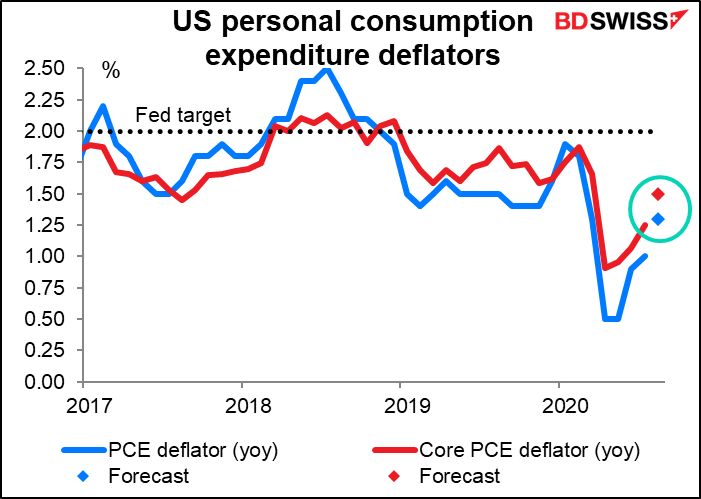

The personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflators that accompany the income and spending data are the Fed’s preferred inflation gauges, although the market pays more attention to the consumer price index. The PCE deflators are both expected to rise, which could be negative for the dollar. That’s because rising inflation with interest rates on hold means lower real interest rates, an important factor in determining exchange rates.

Other major US indicators out during the week are Conference Board consumer confidence on Tuesday, of course the ADP employment report on Wednesday (along with pending home sales), and the Institute of Supply Management (ISM) manufacturing purchasing manufacturers’ index on Thursday.

The other focus in the US will be the first debate between Biden and Trump on Tuesday. The topics will be “The Trump and Biden Records,” “The Supreme Court,” “Covid-19,” “The Economy,” “Race and Violence in our Cities,” and “The Integrity of the Election.” Each segment will last about 15 minutes. The candidates will have two minutes to respond after the moderator opens each segment with a question, followed by discussion.

What to watch for in the debate: Watch for a) Trump’s dilated pupils, strong evidence of drug use; b) bits of white things – parts of pills? — flying out of his nose; and c) whether he can stand without swaying and twitching (evidence of neurological problems). I do hope there will be live fact-checking, but I doubt it.

His speeches have become more and more bizarre recently – for example, at a recent rally in Pennsylvania he told a story that involved his wife Melania referring to him as “Sir,” and talking about NASA he started talking about “fairways” instead of “runways” (does NASA have any runways anyway? I thought they had launching pads.) I’m just sorry the two-minute time limit really restricts him from showing just how unable disjointed his speech is.

What will the debates accomplish? By now there are few undecided voters in the US. I read the occasional piece saying that some “never Trump” people are getting nervous about the Democrats’ restrained response to the recent rioting (an overblown issue in the first place) and are quietly thinking of voting for Trump. Perhaps those people can see Biden they’ll realize he isn’t the Che Guevara lookalike revolutionary the Republicans make him out to be. Otherwise, I expect people will see pretty much what they want to see, just as they did with the debates back in 2016 – and probably every other time, too.

Japan: tankan plus month-end data

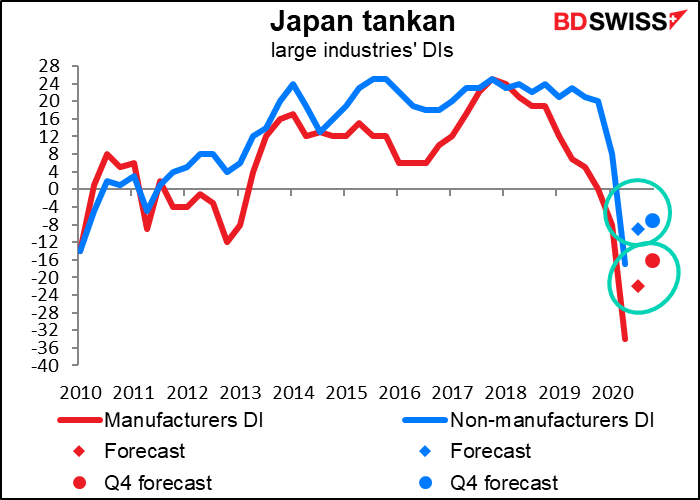

It’s a busy week for Japan data too. In addition to the usual end-month deluge, we have the Bank of Japan’s quarterly short-term survey of economic conditions, universally known by its Japanese acronym, the tankan. This is the most widely watched indicator in Japan

Both the manufacturing and non-manufacturing diffusion indices are expected to be higher, and the forecats for Q4 are expected to be even higher still.

That’s fine, but they’re still nowhere near where they were before the pandemic. I think this will add to the indications that Japan’s recovery is painfully slow – the PMIs for example are still both below 50. Nonetheless, at least they are going in the right direction. Higher is higher and signs of improvement may boost sentiment in Tokyo a bit – which curiously enough would probably be negative for the yen.

As for other Japanese indicators, Tokyo consumer prices come out on Tuesday, industrial production and retail sales on Wednesday, and the labor market data on Friday. Of these, I think the industrial production is probably the most important It’s expecte to tell the same story of a slowing recovery: after a spurt in July, output is expected to grow only slightly in August. .

Eurozone: CPI, German unemployment

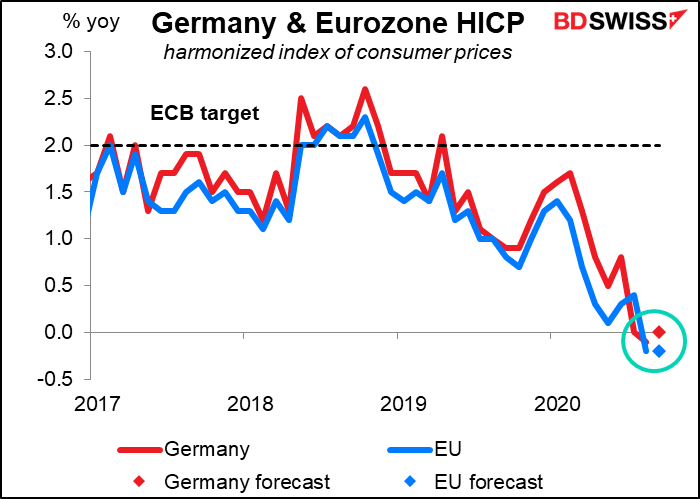

The main indicator from the EU will be Germany’s consumer prices (CPI) on Tuesday follwed by EU-wide CPI on Wednesday. Germany is expected to slip out of deflation but just barely (prices not changing at all from a year earlier) while the EU-wide pace of deflation is expected to remain the same. This shouldn’t affect anyone’s view of the world. At the recent ECB meeting, ECB President Lagarde predicted that “headline inflation is likely to remain negative over the coming months before turning positive again in early 2021.” A continuation of EU-wide inflation modestly below zero will therefore be expected although not welcome.

Germany announces its employment data on Wednesday.

The EU summit that was originally scheduled for this week will be held on Thursday and Friday, 1-2 October. Topics to be discussed include Brexit negotiations (see below), climate change, and the tensions in the mediterranean between Greece and Turkey over energy rights near Cyprus. They will also give their final approval for sanctions against Belarus.

UK: Brexit talks resume

There are no major UK indicators out during the week, but a formal round of Brexit talks resume on Monday. I would be surprised – amazed – gobamacked – if anything substantial were to come out of them. There’s been no change since Britain’s Inernal Market bill was published on 9 September except that now there’s less trust on both sides. The essential problem remains the same: the EU insists on “level playing field” guarantees “commensurate with the scope and depth of the future relationship” between the two regions. This means in effect aligning UK regulations with EU regulations, particularly with regards to state subsidies. However the whole point of Brexit was to allow the UK to forge its own path in the world. There’s no point in breaking away from the EU if they have to follow EU decisions anyway. Thus the odds of a no-deal Brexit are mounting.

I think the market is getting more sensitive to Brexit news and the lack of progess at these talks could be negative for the pound.

Elsewhere, there are no major central bank meetings scheduled.