Weekly Outlook

Peak inflation?

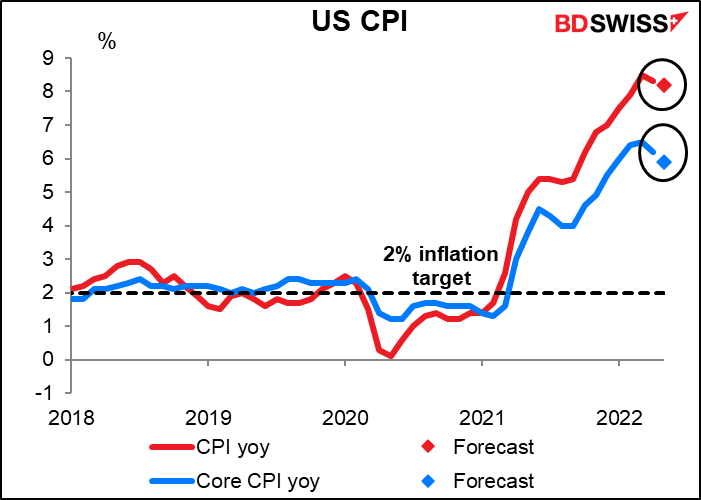

Has inflation peaked? One dot doesn’t make a trend but two might. The US consumer price index (CPI) peaked in March at 8.5% yoy. In April it was 8.3% yoy. The May figure, which comes out next Friday, is expected to fall to 8.2% yoy. Not that big a change in degree, but it’s the direction that’s significant. We may have seen the peak of inflation in the US.

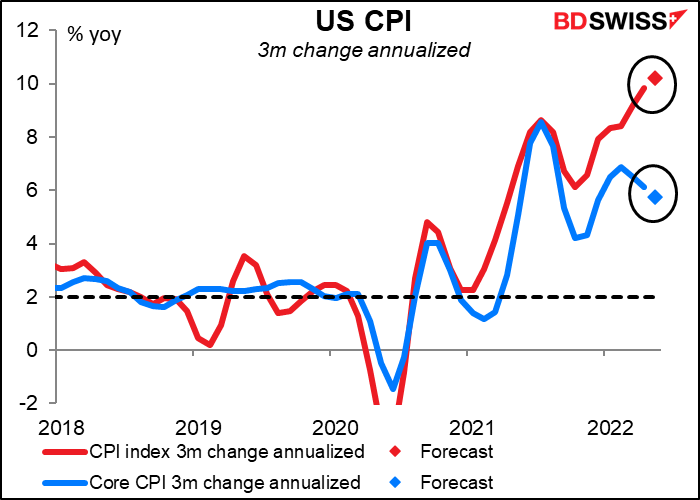

Unfortunately, it might not be that simple. If we look at the three-month change annualized, to capture just the more recent change in prices without base effects, the core rate peaked in February and has been coming down steadily. But the headline rate keeps going higher and higher.

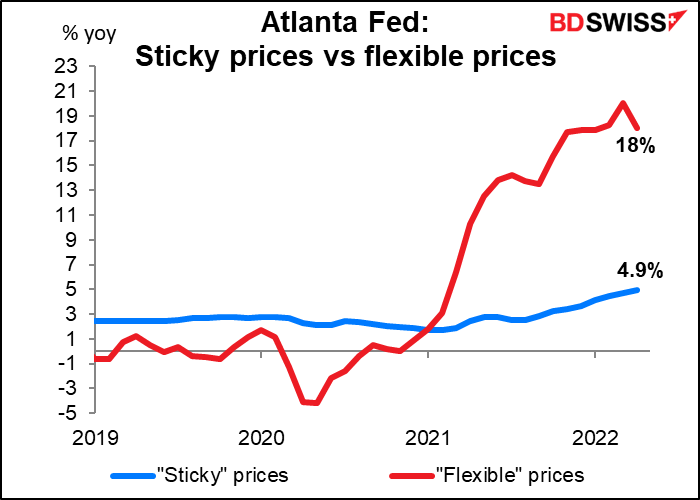

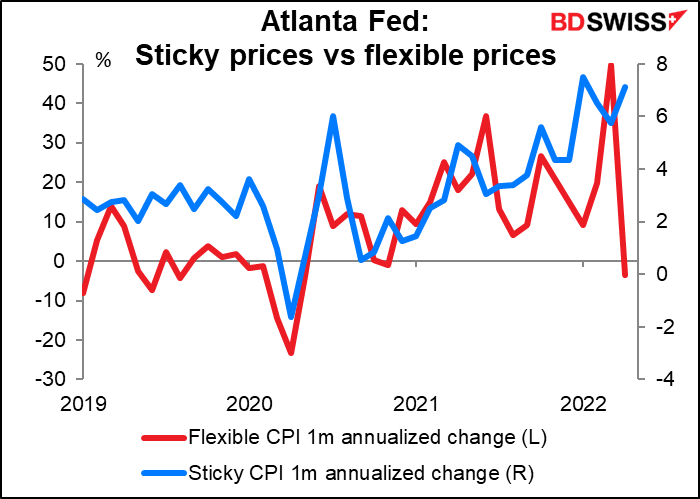

Unfortunately, even if the CPI does peak, it may be some time before it gets down to anywhere near the Fed’s target rate. The Atlanta Fed breaks the CPI’s components into “flexible” ones – items that change price frequently, like gasoline or airplane tickets – and “sticky” prices, like restaurant menus and coin-operated laundries that only change price infrequently. What they’ve found is that the rise in “flexible” prices has started to slow, but “sticky” prices are rising at a faster-than-ever pace. Moreover, even “sticky” prices are rising at more than double the Fed’s 2% annual target.

If we look at the one-month change in prices annualized, we see that “flexible” prices fell in April – perhaps why the headline rate of inflation slowed. But the worrisome point is that “sticky” prices, which seem to have peaked, rose again.

Why is this important? The Atlanta Fed explains:

While a sticky price may not be as responsive to economic conditions as a flexible price, it may do a better job of incorporating inflation expectations. Since price setters understand that it will be costly to change prices, they will want their price decisions to account for inflation over the periods between their infrequent price changes… that component may be useful when trying to discern where inflation is heading.

In that case, the fact that sticky prices are rising at more than double the Fed’s inflation target and that the rate of increase is increasing suggests we can’t expect a rapid decline in inflation.

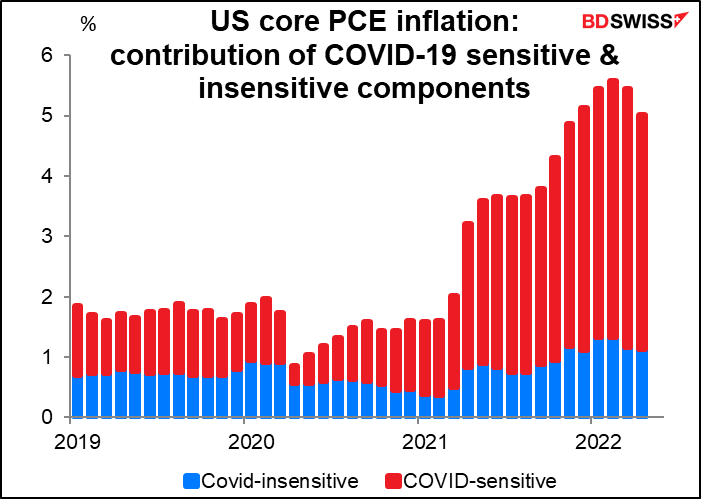

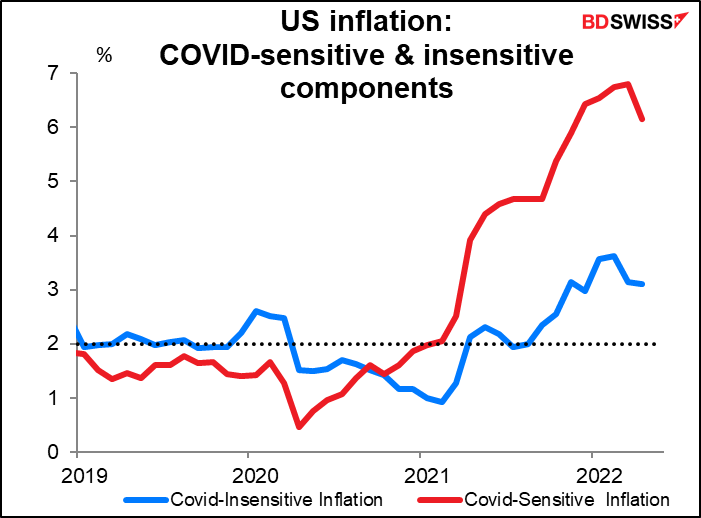

The San Francisco Fed, for its part, dissects the core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator – the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge – into components that were strongly affected by the pandemic and those that weren’t. (It distinguished between the two by looking at what components experienced a sudden change in price around the time that the pandemic began.) What they found was similarly disturbing. True, the rise in inflation is overwhelmingly due to components that were sensitive to the pandemic, which implies that as the impact of the pandemic fades (we hope!) these price rises should slow and could even reverse, as seems to be the case with used cars for example.

The worrying part though is that even COVID-insensitive items are rising in price by slightly over 3% yoy, meaning that inflation has “broken out” of those components directly impacted by the pandemic and spread to other areas. Inflation has become endemic.

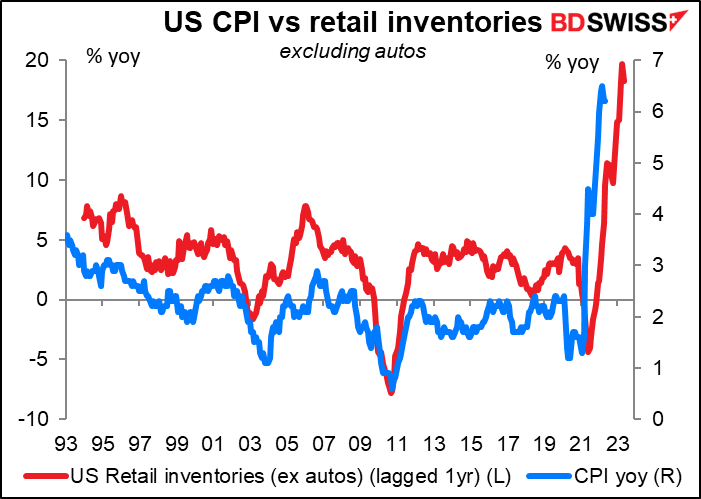

There is one hope though. I’ve noticed that in recent earnings calls, many retailers have remarked on huge increases in inventories. Walmart for example reported a 32% yoy increase in inventories. Assuming that retailers start running sales to reduce these excess inventories, we could see goods prices falling sharply.

There aren’t many other major US indicators out during the week. The main ones are trade balance (Tue), wholesale inventories (Wed), and University of Michigan consumer sentiment (Fri).

Main events: RBA & ECB meetings

There are two central bank meetings next week: the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) on Tuesday and the European Central Bank (ECB) on Thursday.

The RBA is expected to hike by 40 bps, bringing the cash rate up to a more normal 0.75%. That would completely unwind the emergency cuts put in place after the pandemic hit.

The consensus is not unanimous however with many economists forecasting a 25 bps hike to 0.60% and some even forecasting a 50 bps hike to 0.85%.

The debate centers around RBA Gov. Lowe’s comments following the May meeting, when he referred to going back to a “business as usual” policy process. Some people infer from that that the RBA will move by the usual 25 bps per rate hike. The Minutes to the May meeting said that they considered hiking by 15 bps, 25 bps, and 40 bps, but decided on 25 bps because “A move of this size would help signal that the Board was now returning to normal operating procedures after the extraordinary period of the pandemic.”

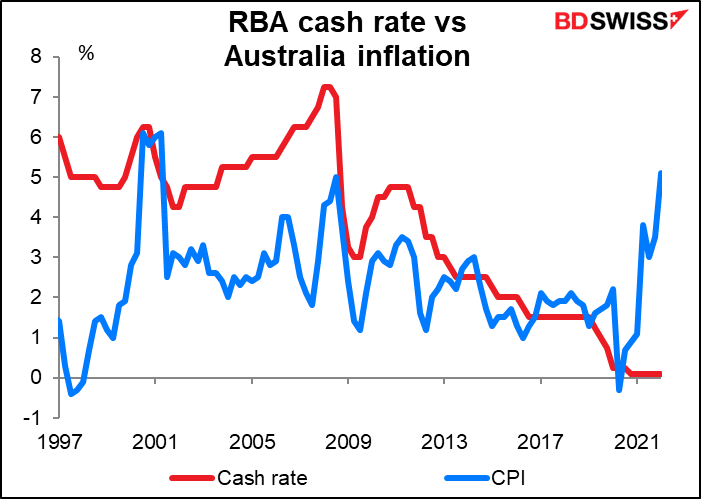

But the Minutes also said that the case for hiking by 40 bps “could be made given the upside risks to inflation and the current very low level of interest rates.” That case remains open still today. Even though the Q1 wage data (both the wage price index and average earnings in the national accounts) was relatively soft, the surge in inflation in Q1 has left the RBA behind the curve. The cash rate has never been this far below the inflation rate – the real cash rate is deeply negative, a stimulative policy that’s no longer necessary. The recent spike in wholesale gas and electricity prices will only reinforce this view as it’s likely to add around half a percentage point to headline inflation this year, meaning that the forecast in the May Statement on Monetary Policy for inflation to end the year at 5.9% now looks likely to be closer to 6.5%.

As for the ECB, rarely has the result of any central bank meeting been so well telegraphed in advance. Numerous ECB officials have said that they are likely to stop their quantitative easing (QE) bond purchases at the June meeting and then start raising rates in July. ECB President Lagarde said just recently (May 23rd) in a blog post, Monetary policy normalisation in the euro area, that “I expect net purchases under the Asset Purchase Programme to end very early in the third quarter. This would allow us a rate lift-off at our meeting in July, in line with our forward guidance. Based on the current outlook, we are likely to be in a position to exit negative interest rates by the end of the third quarter.” How much more specific do you want?

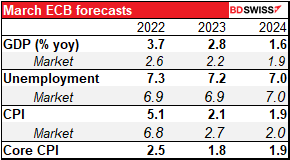

So the main thing next week will be confirmation that net purchases under the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) will end at the end of June, allowing for “lift-off” in July. We will also be looking for the new staff forecasts. They should show inflation rising to 2% in 2024 to justify the policy change.

One point of contention is how quickly to raise rates after they start hiking. President Lagarde and some of her close associates, such as Chief Economist Lane, have been stressing that rate rises will be “gradual,” which is a code word for 25 bps. However several Governing Council members have been agitating for 50 bps hikes. The market is forecasting that the ECB depo rate will be +0.60% by the end of the year. Since there are only four meetings after this one (July, September, October, and December) that implies a hike of more than 25 bps at one of them.

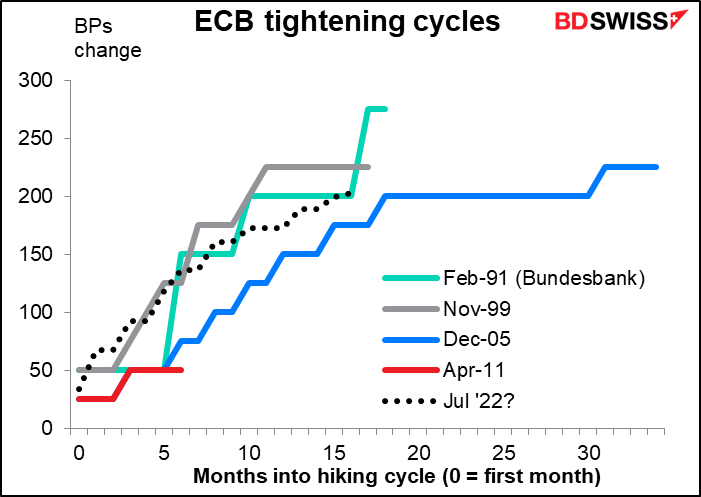

This would be a fairly normal hiking cycle for the ECB (or its predecessor, the Bundesbank).

We’ll also have to see how they redefine their forward guidance. Right now it’s based on their three conditions for liftoff, which are:

- “inflation reaching two per cent well ahead of the end of our projection horizon”

- Inflation 2% “durably for the rest of the projection horizon;” and

- “Progress in underlying inflation is sufficiently advanced to be consistent with inflation stabilising at two per cent over the medium term”

Of course once these conditions have been reached and the rate-hike cycle begins, they’ll need a new set of guidelines to give people a sense of how rapidly they’re going to raise rates. These guidelines will probably follow the outline set out by President Lagarde in the blog post referred to above. It’s hard to sum up exactly what she’s saying there because she’s purposely vague. Given the massive uncertainties facing Europe right now, she can hardly be otherwise.

If we see inflation stabilising at 2% over the medium term, a progressive further normalisation of interest rates towards the neutral rate will be appropriate. But the speed of policy adjustment, and its end point, will depend on how the shocks develop and how the medium-term inflation outlook evolves as we move forward.

One thing is certain though: she’ll definitely repeat her call for “optionality, gradualism and flexibility in the conduct of monetary policy.”

Likely impact: If President Lagarde pushes back on market pricing of more than 25 bps hike per meeting, we could see EUR weaken afterward. On the other hand, if she validates market pricing by holding out the possibility of a 50 bps hike (or at least a hike of more than 25 bps) then the market is likely to start discounting even more tightening and EUR would be likely to strengthen. I expect the former; I think she’ll push back against market speculation and as a result EUR may weaken afterward.

Other indicators

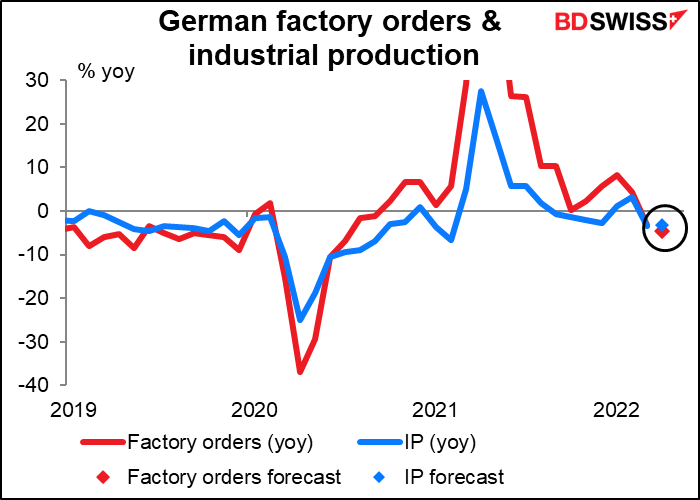

For the EU, the main indicators will be German factory orders (Tue) and industrial production (Wed). Both are expected to be down year-on-year, with orders forecast to be down month-on-month too. Germany’s export-led output is apparently still struggling.

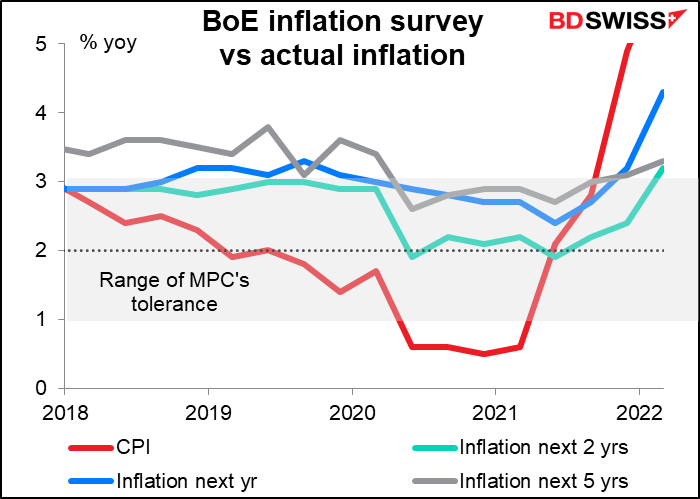

There’s not much on the schedule for Britain next week. The only point of interest (aside from the usual political machinations) will be the Bank of England/TNS inflation expectation survey. Central bankers live in dread of inflation expectations becoming “unanchored.” That is, if people think inflation is likely to continue to be high, they’ll operate accordingly (remember what I said above about how changes in “sticky prices” provide information about what people think inflation is likely to be in the future – if they think inflation is likely to be high, then when they change their prices they’ll hike them accordingly.) The danger for the Bank is not just that the expectations about inflation a year from now will rise, it’s what the inflation expectations two years from now (actually, for the year starting one year from now, or 1yr/1yr forward) or what they think the five-year inflation outlook is likely to be. As of the last reading, the latter two were just outside the Bank’s 1%-3% range of tolerance (at 3.2% and 3.3%, respectively). If they climb further then the Bank may begin to think that it’s losing control of inflation and will have to tighten faster.

Japan releases its current account on Wednesday and corporate goods price index (CGPI) (aka producer prices) on Friday. The CGPI is expected to rise further, putting more pressure either on inflation or on corporate profit margins. That could be JPY-positive, but I doubt if the Bank of Japan will respond so any rally probably wouldn’t last long.