Weekly Outlook

Was Powell Worth the Wait?; Final PMIs, NFP, Mnuchin, RBA

The week gone by was a wait of time, so to speak. The market was waiting to hear what Fed Chair Powell would say about the central bank’s Monetary Policy Framework Review.

In the event, the new policy is a lot like the old policy was in fact, if not in theory. Powell called it “a flexible form of average inflation targeting.” “…We will seek to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time,” Powell said. “Therefore, following periods when inflation has been running below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.”

Note that this leaves them lots of wiggle room:

They aren’t going to compensate one-for-one. Powell stressed that “we are not tying ourselves to a particular mathematical formula that defines the average.” So just because inflation was 1% one year doesn’t mean it will have to be 3% the next year.

They said they will “aim to achieve” above-target inflation, not that they “would” achieve it. Big difference! This wiggle room allows them to avoid the problem that the Bank of Japan has faced of year after year promising to hit a target that they can’t. Later in the Q&A he was even less committal, saying that “we’ll aspire to have inflation run above 2% after periods in which it runs for an extended period below 2%.” I’ve never before heard a central banker talk about “aspiring” to hit a monetary target.

During the overshoot period, inflation would be “moderately above 2%.” How much is “moderately”? “Which is to say, not large” Powell explained in the Q&A.

“For some time” is also allows them a lot of discretion for how long to allow an overshoot. Powell explained that this means “not permanent.”

The key point in my mind though is, they are not committed to achieving this overshoot. They say that “policy will aim to achieve it” or that they “aspire” to achieve it, but they’re not required to. And given that policy now is “aiming to achieve” 2% inflation but hasn’t even managed to do that 75% of the time, I fail to see how they’re going to achieve “moderately above 2% for some time.” With no guarantee of ever having negative real yields, the new policy is less dovish than it might have been.

Of course it could be that as the economy recovers from the pandemic, various bottlenecks emerge due to reduced capacity and inflation does pick up. In that case, the market will be glad to know that the Fed isn’t going to rush right in to kill off the recovery. But from a practical point of view, I don’t see how this changes things from the outlook a month ago, for example, when the FOMC and the market were expecting rates to be at zero indefinitely anyway.

Powell reinforced the wishy-washy nature of the new policy in the Q&A session when he stressed that it was important for people to “understand that this is not a formulaic approach…the Committee will continue to consider all of the things that it typically considers in making monetary policy…” In that case, it’s hard to see what has really changed if we assume that inflation isn’t going to be back up to 2% any time soon anyway.

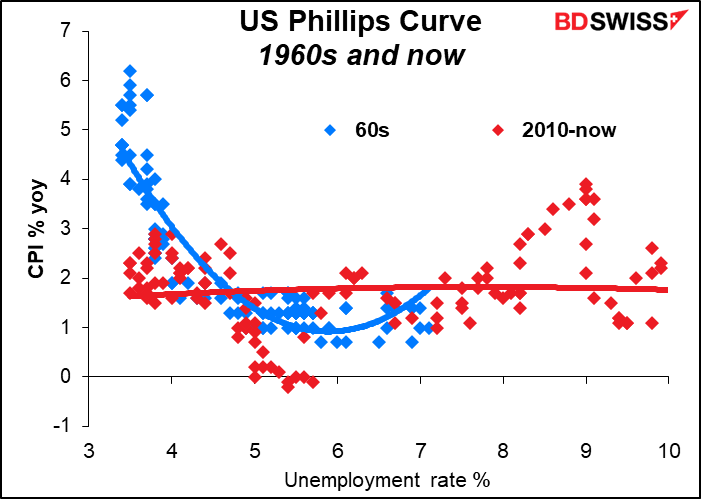

As for employment, the other half of their dual mandate, they acknowledged that the Phillips Curve that they learned about in Econ 101 – the idea that as unemployment goes down, wages go up and inflation starts to rise – no longer holds, for whatever reason. They therefore made a subtle change: “our policy decision will be informed by our “assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its maximum level” rather than by “deviations from its maximum level” as in our previous statement.” Powell said this change “reflects our view that a robust job market can be sustained without causing an outbreak of inflation.”

My interpretation is that by replacing “deviation” with “shortfall,” they are making the employment mandate one-way. “Deviation” could be above or below the maximum level, while “shortfall” is only below. They might loosen policy if employment is below what they estimate is maximum employment, but they are not going to tighten policy if employment goes above what they think is maximum employment, unless of course it actually does spark higher inflation. Previously they might have started tightening as unemployment got to what they thought was the lowest it could get without starting inflation – the so-called “non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment,” or NAIRU. What they’re saying now is that they won’t know in advance what NAIRU is, and so they’ll just have to wait until inflation does start accelerating.

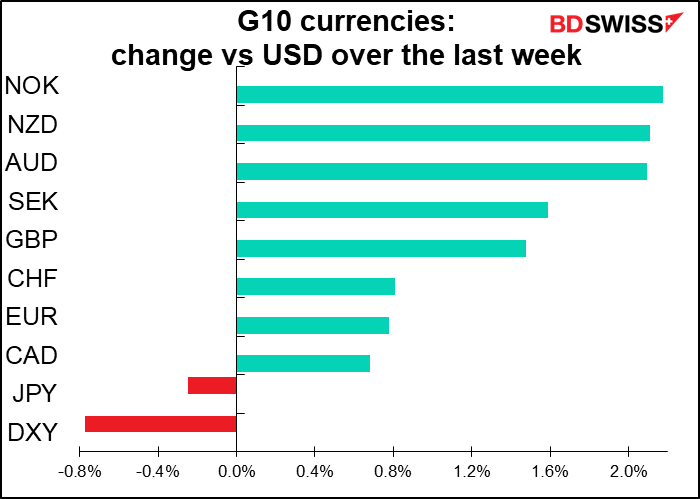

Implications for the dollar: A lot depends on what people were expecting. The new structure has the name of “average inflation targeting,” but with no requirement that undershoots be followed by an equal and opposite overshoot, real yields are not going to be as negative as they would have been under a stricter regime operating under a set formula. What it probably means in practice, at least at the moment, is that the Fed will keep interest rates unchanged at near zero indefinitely. But of course that’s what the market is expecting anyway. The FOMC and the market agree that rates are likely to be on hold indefinitely. No change in the rate outlook = no change in the USD outlook.

With the new Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy

now released, there’s a good chance the FOMC might revise its rate guidance and balance sheet policy at the 16 September meeting. They’re likely to adjust their forward guidance with regards to both rates and asset purchases in line with the new framework.

Powell wasn’t the only person presenting on Thursday, by the way. European Central Bank (ECB) Chief Economist Philip Lane also made a presentation in which he hinted that the ECB isn’t through easing yet. See below for details.

The coming week: final PMIs, NFP, Mnuchin, RBA

That was the big event last week. What’s up in the coming week?

Globally, the main event will be the release of the August purchasing managers indices (PMIs), including the final ones for the major industrial economies that have preliminary versions. The manufacturing PMIs will be on Tuesday and the service-sector PMIs on Thursday. This includes as usual the Institute of Supply Management (ISM) versions from the US. The data will be important to confirm whether the global economic recovery is stalling, as the preliminary PMIs suggested.

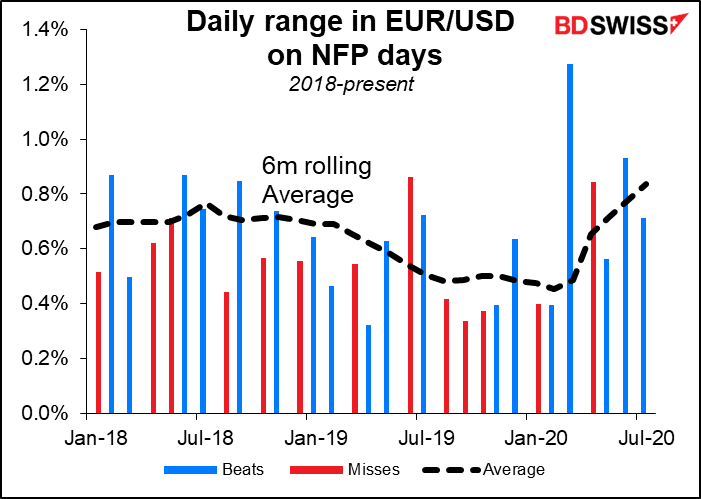

Once again it’s nonfarm payrolls (NFP) week! Although we’re now getting weekly updates on the employment situation via the initial jobless claims, old habits die hard and people are still putting a lot of weight on the NFP. Nonetheless, the volatility on NFP days isn’t always what you might imagine given what a fuss is made of the figures. The range on the day (high minus low as a % of low) is often less than on a normal day, probably because people hold off trading ahead of the data and then fail to get a clear impetus to trade once the number comes out.

We can see that in the past, USD/JPY was the more volatile pair to play, but this year EUR/USD has shown more of a reaction to the figures.

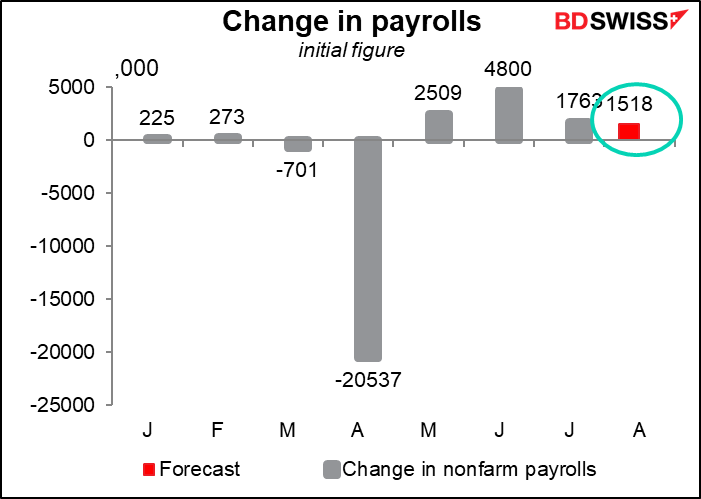

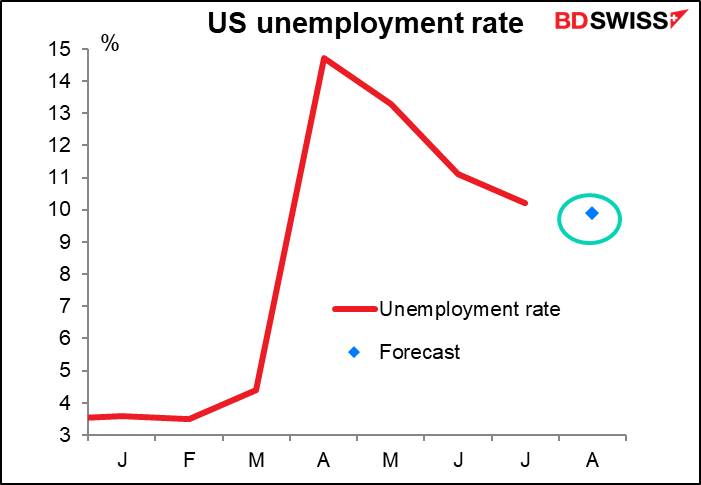

The good news this month is that payrolls are expected to increase and the unemployment rate is expected to decrease. The bad news is that the pace of improvement is slowing. With 16.3mn unemployed workers – and that’s with the Bureau of Labor Statistics admitting it’s counting them incorrectly – an increase in employment of only 1.5mn in a month is slow progress. (A better estimate of the number of unemployed might be the 27mn people claiming unemployment benefits.)

The ADP report on Wednesday is forecast to show a comparable 1250k increase in the number of jobs.

By the way, there’s going to be a change in the way the weekly jobless claims are calculated starting this coming week.

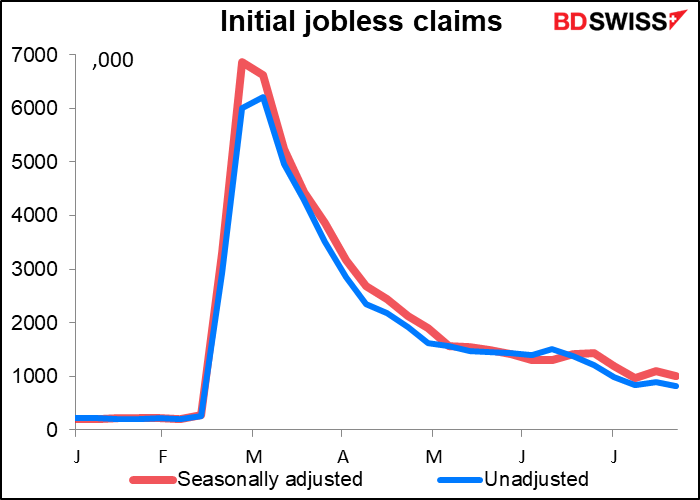

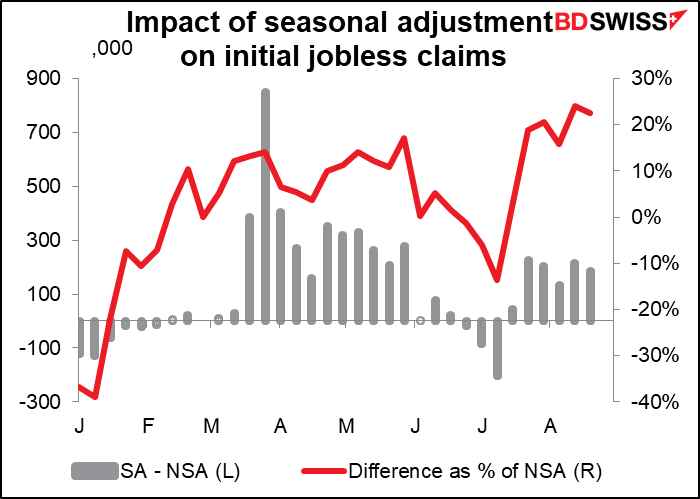

Unemployment is quite seasonal. For example, many people who work in schools get laid off every year in May and June and file for unemployment benefits. They then get hired back again in August and September. Similarly with retail workers before and after Christmas. The statisticians iron out these predictable changes using various mathematical technics to calculate “seasonal adjustment factors.” The way the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) makes these changes is by multiplying the not-seasonally-adjusted (NSA) figure times a seasonal adjustment factor. This is the generally accepted method and it usually works well, because the seasonal effect is assumed to be proportional to the level of the series. That is, if the level of unemployment rises or falls an unusual amount, the seasonal effect is assumed to be unusually large as well.

However, because of the pandemic, the number of unemployed persons rose by a never-before-seen number (6.2mn NSA the week of 3 April). This was a 53-standard-deviation event, which should in theory not be seen before the universe stops expanding, cools down and then implodes on itself. Furthermore, the timing of these changes was out of whack with the usual seasonal pattern, since everyone’s schedule is disrupted.

Because the NSA data is multiplied by the seasonal adjustment factors, it exaggerates these unusual moves even more. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Thursday announced that it would therefore change the method of seasonally adjusting the figures to additive. That is, if 50,000 people usually lose their jobs in a certain week, they will add those people back in, rather than multiplying the NSA figure.

The BLS already made the same change to the Job Offers and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) starting with June. One wonders if a similar move is coming to the NFP and unemployment data and if so, what it will look like.

Outside of employment data, the US schedule includes the Beige Book on Wednesday, as usual two weeks before the next FOMC meeting. And the trade figures will be released on Thursday.

Treasury Secretary Mnuchin will testify on Tuesday before the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis. It will be interesting to hear him explain why the Trump Regime has been unable to extend the benefits in the CARES act and what they plan to do to support the millions of unemployed persons.

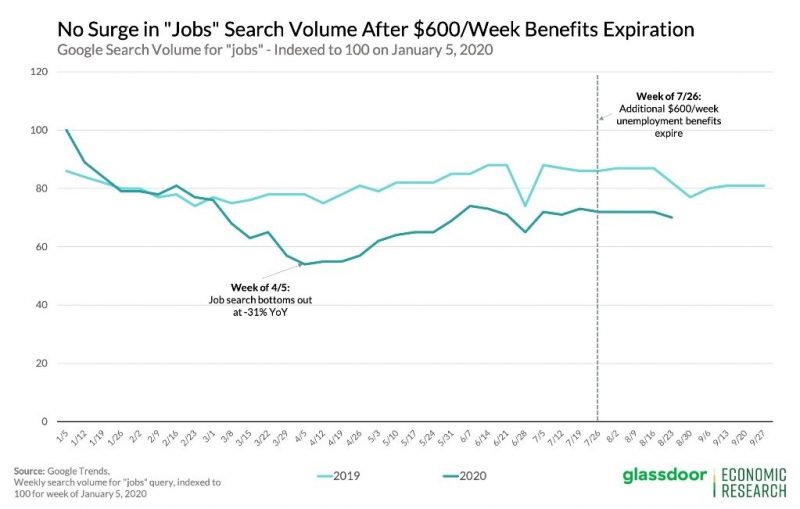

I have to give the White House credit on this one — Trump did come up with some money for the unemployed when his pals in the Senate refused. The senators claim to be worried about creating financial incentives that would dissuade the 27mn people unemployed persons from taking the 5.9mn jobs that are available. However looking at Google searches, there’s been no appreciable increase in job searches since the payments ended. So maybe they’ll have to think of another excuse for not giving money to poor people, some of whom might not be of the same ethnic group they are.

The US will be picking up pieces after Hurricane Laura devastated the Gulf of Mexico. So far it looks as if the storm left most of the oil refining capacity intact, but this will have to be clarified over the coming days. A reduction in refining capacity could put downward pressure on crude prices and therefore would be negative for CAD, NOK and RUB. But at the time of writing it seems to have had little impact.

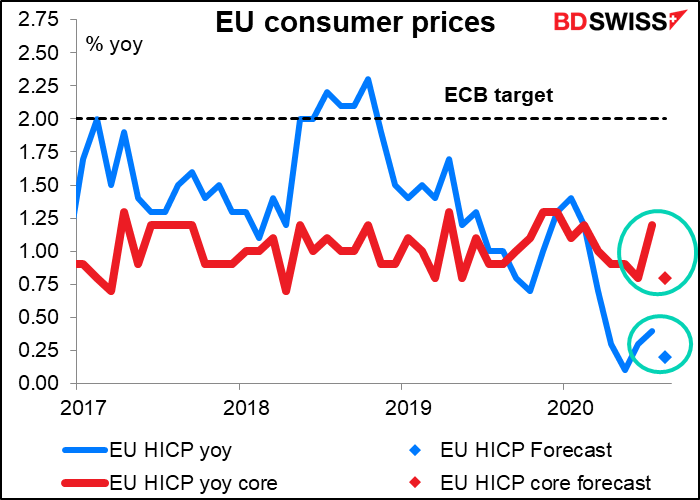

In the EU, the main indicators of the week will be German inflation on Wednesday and EU-wide inflation on Thursday. German inflation is expected to slow, and it’s not all energy, as EU-wide core inflation is expected to slow as well.

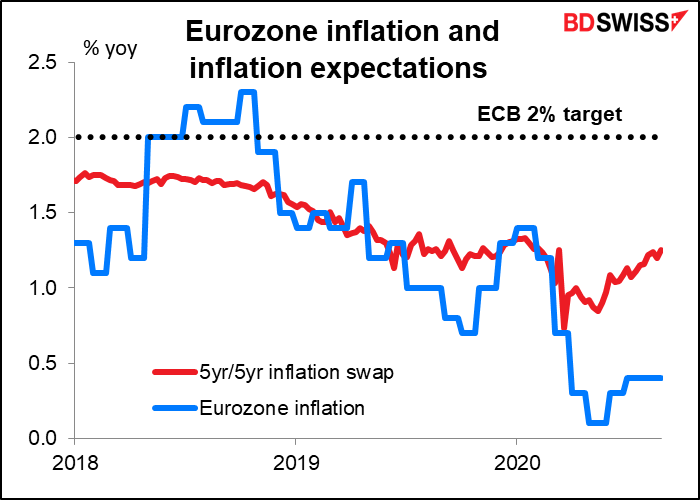

A further fall in inflation could jolt the European Central Bank (ECB) into adjusting policy at its 10 September meeting. At Thursday’s Jackson Hole seminar, ECB Chief Economist Philip Lane described a two-stage monetary policy challenge. He said policy must first counteract the negative shock from the pandemic, and once that is accomplished, “to ensure that the post-pandemic monetary policy stance is appropriately calibrated in order to ensure timely convergence to our medium-term inflation aim.” He continued, “To these ends, the ECB Governing Council stands ready to adjust all of its instruments, as appropriate.” The fact that he separates these two stages suggests that he’s not certain they have achieved the latter. Indeed the minutes of the 16 July Governing Council meeting showed more discussion than usual about the weakness of longer-term inflation expectations, which only stands to reason: the ECB’s own forecasts are that inflation will remain below 1% at least until end-2022. A downward revision to these already-low inflation forecasts in September’s new staff forecasts could be the trigger for further policy action and a weaker EUR.

Financial stress in the Eurozone has almost come back to normal…

But inflation expectations remain well below target

Germany also announces its factory orders on Friday.

There are no formal Brexit talks scheduled for the week, nor any major UK statistics. The negotiations will start up again the following week (7 September). Don’t expect any breakthroughs, though. The breakthrough, if it does occur, will either be last minute or not at all. I’m leaning to last minute, although it seems that the EU side is increasingly convinced that Britain is serious about crashing out without an agreement.

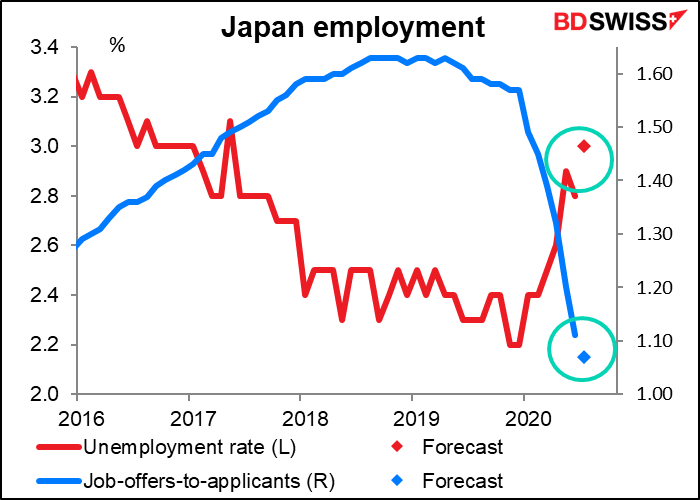

It being the end of the month, we get the usual deluge of data from Japan, including industrial production and retail sales on Monday and unemployment, job-offers-to–applicants ratio and the quarterly capital spending figures on Tuesday.

Industrial production is expected to be up 5.0% mom, which sounds good except that would still leave it down 17.2% yoy, or 15.5% below the average level of January and February. Japan is one of the few countries where the manufacturing PMI is still below 50, i.e. manufacturing is still contracting. That’s particularly bad for an economy that still has a large manufacturing sector.

Japan’s unemployment situation seems to be better than most other countries, but a lot of it is just smoke-and-mirrors as special furlough support payments and housewives leaving the workforce artificially hold down the unemployment rate. The collapse in the job-offers-to-applicants ratio is a better indicator. Still, as mentioned above there are 5.9mn jobs for 27mn unemployed persons in the US, or a job-offers-to-applicants ratio of 0.22, so Japan isn’t doing too badly on a comparative basis.

The only G10 central bank meeting during the week is the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). They are going to be a particular problem for me, because they are on hold indefinitely and yet I have to write about them 11 times a year, more than any other major central bank.

With AUD fairly stable and the benchmark 3-year yield trading only a basis point away from their 0.25% target, the Board has little reason to take any action at this meeting. I assume that they’re going to remain on hold and I would look for a comment in the minutes similar to this one that appeared in the minutes of both the July and August meetings:

“…members agreed that there was no need to adjust the package of measures in Australia in the current environment. Members agreed, however, to continue to assess the evolving situation in Australia and did not rule out adjusting the current package if circumstances warranted.”