Weekly Outlook

Let’s get Fiscal!

Which song do you like better? I like Olivia Newton- John’s version from 1981. There’s also a different song out this year by Dua Lipa with the same title that refers to Olivia’s song. If you like that version, you might be interested in hearing it in Korean, sung by the Korean singer Hwasa.

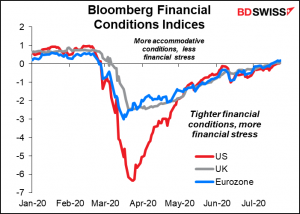

Whichever, market are now going to get fiscal as the role of monetary policy is played out. With interest rates at or near the zero bound, bond yields as low as they’ve ever been, and financial conditions back to normal in most of the developed world, central banks have accomplished what they needed to.

Even though the highlight of the week will probably be Wednesday’s meeting of the US Fed’s rate-setting body, the US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the real action will be in Congress as they try to hammer out an agreement on CARES Act 2.0. Fiscal policy is what matters now, not monetary policy.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act is the $2.2tn economic stimulus bill that was passed in March. It provides supplemental unemployment insurance benefits of $600 a week to unemployed persons, in addition to the base pay from state unemployment offices (which is on average $372/wk). But those benefits are set to expire on 31 July. In order for there to be a smooth continuation of the supplemental benefits, Congress would have to approve the new CARES bill by today – which ain’t gonna happen.

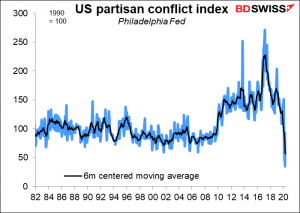

Fortunately or unfortunately, the crisis is focusing people’s minds, and the fact that there’s an election in 102 days is making many Republicans forget some of their cherished truths – such as, giving money to rich people is “incentives to job-creators” while money to poor people is “disincentives to work,” etc etc. As a result, the partisan wrangling between the two parties, which hit a thirty-year high early in the Trump regime, is now at a thirty-year low. They should be able to cobble together something eventually.

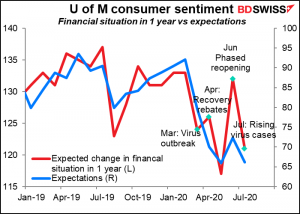

The problem is, uncertainty over our income in the future affects how we spend money today. If over 20mn people risk losing half their income, they’re likely to cut back on their spending right away. That will only cause the economy to slow further.

As the U of Michigan report itself said,

“Another aggressive fiscal response is urgently needed that focuses on financial relief for households… While financial relief is clearly needed for the most vulnerable households, that relief will not stimulate the extent of renewed consumer spending necessary to restore employment and income to pre-crisis levels anytime soon. No single policy could provide financial relief and stimulate economic growth, and without both, neither one could be ultimately successful. Unfortunately, there is little time left on the political calendar for Congress to act… Without action, another plunge in confidence and a longer recession is likely to occur.”

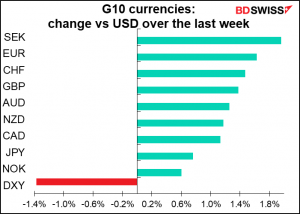

This “fiscal cliff” problem is particularly bad for the US. How does it compare to the rest of the world? Generally speaking, it’s lurking elsewhere, as rescue packages instituted early on in the crisis now expire and governments have to decide whether to renew them. But nowhere is it approaching with the same severity and near-term deadline as in the US. The problem of diminishing fiscal aid for the US economy, in contrast with the situation in other countries, is likely to become a major negative for the dollar in the coming weeks if nothing gets done.

Here’s a summary of the situation in other countries. (With thanks to Bloomberg News for much of the following information)

In Europe, there’s less of a “cliff” and more of a “gradual decline” as a number of support measures are likely to undergo adjustment. In Germany for example, one of the major supports for the German economy – the provision of wage subsidies for companies that keep people on their payrolls – has been present in one form or another for over 100 years. Those subsidies won’t expire for a year or more. The aid may start to dwindle in the autumn, although Finance Minister Scholz has said the government will reassess the situation at that point to see if further help is needed.

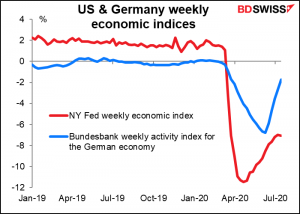

In any case, the downturn doesn’t appear to have been as sharp in Europe as in the US (although the Q2 GDP figures, which come out next week, suggest otherwise – but we’ll get to those later.) Looking only at Germany, the downturn was shallower and the upturn has been faster, so the country is in better shape than the US.

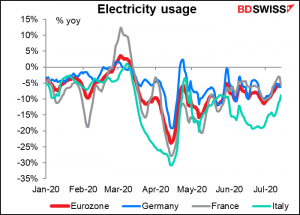

And looking at electricity usage as a proxy for economic activity as a whole, Europe seems to be fairly well on its way to recovery. (The Eurozone figure in this graph is comprised of the seven largest EU countries.)

In neighboring France, the government is gradually moving from blanket insurance to targeted aid. There won’t be a cliff, but some sectors will find less support. Unemployment is likely to rise somewhat. In Italy, the problem isn’t so much falling off the cliff as it was getting to the top of it. The government was slow in enacting the aid, but now that it has it in place, it’s extending it as necessary. PM Conte has said the country “doesn’t abandon workers” and will do whatever is needed to keep supporting the economy.

Britain does have a cliff, but it won’t arrive until the end of October, when the furlough program – which currently pays 80% of wages – ends. That’s also the date when support for self-employed workers will finish. Other support programs, such as the reduction in sales tax for hospitality firms, also have definite ending times. The hope is of course that by the time these deadlines roll around, activity will be getting back to normal and the private sector can take over. Do I hear Frank Sinatra singing “The Impossible Dream” off in the distance? I expect that the government will have to reconsider these deadlines and will wind up extending some of these benefits. After all, with interest rates negative, why not borrow the money and spend it?

Japan’s cliff is far away. The Bank of Japan’s two lending programs and CP/corporate bond purchase programs are good for this fiscal year, i.e. they don’t expire until 31 March next year. The deadline for applying for JPY 100,000 is coming up fast (my daughter couldn’t get it, unfortunately) but the deadline for applications for cash for freelancers and small firms is next January, while the country’s furlough program has been increased until 30 September.

Canada too has a lot longer to run. The Canada Emergency Response Benefit, which provides citizens with a monthly income, runs until 3 October, while the wage subsidy plan for workers who are kept on the books instead of being laid off is being extended until December. There’s also a loan program for small businesses that has a 31 August application deadline.

In short: for the time being, the “fiscal cliff” is largely a US problem. It is therefore likely to weigh on the dollar, in my view.

Next week: FOMC, GDPs

There’s a lot of data on the schedule next week. The main focus will be on preliminary 2Q GDP figures from the US, Germany, and the Eurozone. Canada, which releases monthly GDP figures, will be announcing its GDP for May.

The other focus, as mentioned above, will be Wednesday’s meeting of the US Fed’s rate-setting body, the US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Let’s discuss that first, then get to the data.

This month we’ve had meetings of the Reserve Bank of Australia (7 July), Bank of Japan (15th), Bank of Canada (15th) and European Central Bank (16th). While some tinkered with their forward guidance, none changed their rates or their programs significantly. I expect the same from the Fed: some comments on the current situation, concern about the future, and a willingness to do more if necessary. I don’t expect much change in the statement following the meeting. The important points will only come out during Chair Powell’s press conference and the minutes, which will be released on 19 August.

The Fed has dealt with the financial market emergency stemming from the virus. As we saw in the graph above, financial conditions are back to normal. The market’s expectations of the future path of Fed funds is the same as the Committee’s, meaning they don’t have to correct any misunderstanding of their views. All the FOMC members who’ve spoken recently have agreed that policy should remain accommodative indefinitely. They say they might want to do more, but not right now. “…Right now there’s just a lot of uncertainty,” said Dallas Fed President Kaplan (voter) on 16 July. “So for me, I would prefer to be patient and wait a little bit more and get more visibility…I’m not talking about waiting that long. But I think there’s six, eight weeks in this; six weeks in this situation is still an eternity.” In short, there’s not that much for them to do right now.

Against this background, the Committee can get back to deliberating about the review of monetary policy strategy, tools, and communications that it announced in November 2018. NY Fed President Williams recently said that the review would be completed “later this year,” which isn’t much help.

They can discuss some of the topics that were brought up in the review, such as how changes to the inflation framework should be spelled out and implemented, what changes if any are necessary for their forward guidance and asset purchases, etc etc. Powell may give some details of those discussions in his press conference following the meeting. If past performance is any guide to future performance, he may then preview them in the Fed’s virtual “Jackson Hole” meeting, to be held 27-28 August, on the theme “Navigating the Decade Ahead: Implications for Monetary Policy.” They could then implement the changes at the September meeting.

What shape might those changes take? The minutes to the June meeting showed that “a number of participants spoke favorably of forward guidance tied to inflation outcomes that could entail a modest temporary overshooting of the Committee’s longer-run inflation goal but where inflation fluctuations would be centered on 2 percent over time.” (emphasis added) Several FOMC members (Evans, Harker, and Brainard) have said recently that they approve of this approach.

Accepting – or even encouraging – an overshoot of the 2% target, perhaps to make up for times when inflation has undershot the target, would be a big change for the Fed, one that would have to be explained carefully to market participants to avoid confusing the markets. That’s probably why “various participants” noted at the June FOMC meeting that “the Committee should complete its monetary policy framework review in the near term, including revising the Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy. Such a revised statement would communicate to the public how the Committee views its policy goals and provide additional context to the Committee’s policy actions.” Although to be honest an overshoot of the 2% target doesn’t isn’t anyone’s big worry at the moment – deflation seems to be a more immediate concern.

One other big topic of discussion recently has been yield curve control: targeting the longer-end of the yield curve as well as the short end. Japan started it and Australia has also implemented it. So far they’ve largely agreed it’s worth considering, but as far as I remember no one has specifically come out in favor of it.

The data: GDP, personal income & spending, EU CPI, Japan end-of-month…lots of goodies

There’s a lot of data coming out during the coming week.

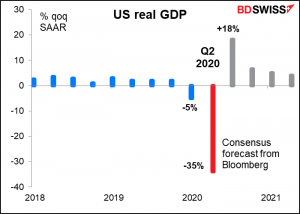

The GDP figures are expected to be wild. Q2 is when most of the economies bottomed out. They’re expected to be figures like we’ve never seen before and, one hopes, will never see again.

US Q2 GDP Is expected to be down 34.5% (qoq SAAR). Estimates range from -40% to -26%. For what it’s worth, the various regional Fed’s “Nowcasting” estimates are: Atlanta, -34.7%; New York, -14.3%; and St. Louis, -32.0%. The NY Fed is an outlier here.

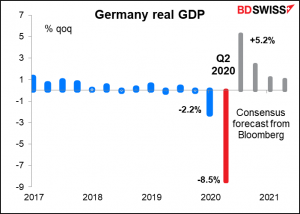

Germany is expected to show a decline of 8.5% qoq.

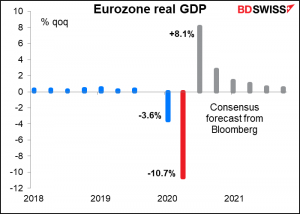

Other countries in the Eurozone did even worse than Germany (France is expected to come in at an astonishing -15.6%). As a result, the Eurozone as a whole is forecast to show a drop of 10.1% qoq.

Germany and the Eurozone may look to have a much shallower dip than the US but remember that they report on a quarter-on-quarter basis, while the US reports qoq annualized. Germany’s -8.5% fall, if expressed the same way as the US’ is, would be -30% qoq SAAR, while the Eurozone’s -10.7% would be -36.4% qoq SAAR. So all fairly comparable to the US’ -34.5% And remember, no one really has a clue what the figures will be, as the data is just too too far away from normal to make any accurate predictions.

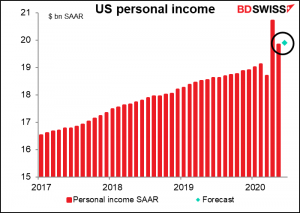

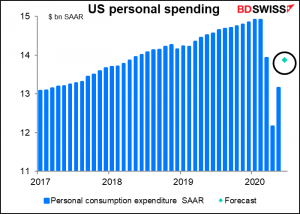

The US personal consumption and spending data is expected to show once again that incomes are holding up well – that the government’s programs have boosted people’s finances overall. (This is what horrifies Republicans so much – that some people have actually been making more money on unemployment than when they were working. How despicable! They’re worried that people won’t want to go back to work – as if 20mn unemployed people could all find work now.)

At the same time, personal spending remained relatively subdued – about back to the level of March, but some 7% below the level of January and February.

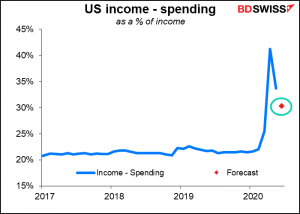

As a result the savings ratio (defined here as income – spending as a % of income), which for years was quite stable at around 19%-21%, hit a record high of 41% in April. It came down to 34% in May and is expected to fall further to 30% in June. That’s lower but still quite high from a historical perspective. Remember that one person’s spending is another person’s income. This savings therefore represents lost income to someone.

This is what I was discussing earlier about the threat to the recovery from financial insecurity – if people are unsure about their future income, they’ll cut back on spending, which causes income insecurity for someone else. That dynamic is still being played out, whether by choice or by default (maybe people simply can’t spend money like they used to because the restaurants, gyms or whatever that they used to spend it on are still closed).

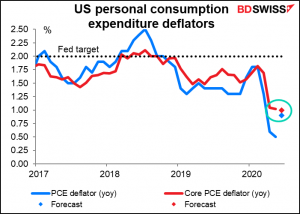

The personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflators that come out with the personal income & spending data are the Fed’s preferred inflation gauges, although they don’t get as much attention as the better-known consumer price index (CPI). The headline figure is expected to jump as a result of higher oil prices, but the core PCE deflator – which is what the Fed pays most attention to – is forecast to stick at 1%, only half the Fed’s target. As I mentioned earlier, above-target inflation is a concern for the distant future.

Other important US indicators coming out during the week include durable goods on Monday, Conference Board consumer confidence and Richmond Fed index on Tuesday, and advance goods trade balance and pending home sales on Wednesday. And as always, the weekly initial jobless claims and continuing claims on Thursday. They’ll be a particular focus after this week’s unexpected and disappointing rise in initial claims.

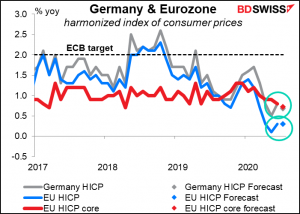

For the Eurozone, the other main indicator will be German CPI on Thursday and EU-wide CPI on Friday. Headline EU-wide CPI is expected to remain at almost no growth yoy, while core inflation – which what the ECB pays attention to – is forecast to slip one tick further away from their target. No fear about overshooting the inflation target here, either.

For Japan, the big day is Friday morning, when the usual end-of-month data dump takes place.

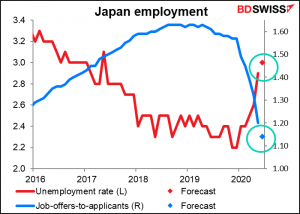

The unemployment rate is expected to rise only modestly, while the job-offers-to-applicants ratio is forecast to fall further but remain above 1.0. As I’ve discussed previously, much of this good performance is an optical illusion caused by various schemes that pay companies to furlough workers instead of laying them off, plus many of the workers who do lose their jobs withdraw from the labor force and so are not counted as unemployed. The employment situation in Japan isn’t as wonderful as it seems.

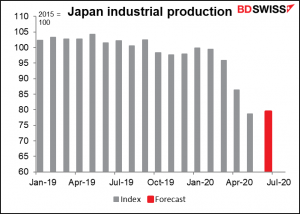

Japan’s industrial production meanwhile is expected to show little improvement from its extremely low levels – down 20% from the January-February average. I don’t have a breakdown of the composition of Japan’s IP, but I suspect that the collapse of auto sales worldwide may have a lot to do with this.

In any event, Japanese indicators haven’t been moving the yen recently. USD/JPY has been remarkably steady, with most of the fluctuations coming either as a result of global “risk-on” and “risk-off” behavior or due to general USD strength or weakness.

Britain has no major indicators out during the week, and Brexit talks finished up yesterday with no conclusion.